What If? Stacy Cobb on Becoming a Statistician & Barrier Breaker

By: Cynthia Adams | Photos By: Nancy Evelyn & Amy Freeman

She is not a stereotypical statistician. But actually, Stacy Cobb is a statistic of her own. Cobb, who made history as the first African American to earn a doctorate in Statistics at the University of Georgia on May 6 this year, says she “dug deep” in order to make that happen.

“I don’t think you see how you do it until you make it through, and then you realize it is possible.”

Although neither of Cobb’s parent had college degrees, as a young student she couldn’t stop thinking “what if?” When she became an undergraduate at Savannah State University, Cobb was among the first cohorts of STEM programs for minorities there.

Now she works as a biostatistician for UNC Healthcare in Morrisville, N.C. Cobb applied herself to mathematics, which was always her favorite subject as an earnest and accomplished young student growing up in Savannah, Ga. Math was compelling and a natural outlet for her.

And, the affable scholar says she played just as hard as she worked. She readily confesses to some “guilty pleasures.” For instance, Cobb loved and still loves political rap, the singer Bruno Mars, Chipotle, drawing, shooting hoops or watching basketball (especially the Celtics), roller skating, and, of course, spending time with her two-year-old son, Ayden.

Cobb first entered graduate studies at Stony Brook University, N.Y. in a bridge-to-doctorate program.

Yet she found that Stony Brook was not a good fit for her. Cobb struggled to mesh with the program, and the struggles she faced there undermined her self-confidence. Nonetheless, she persevered. She earned a master’s degree and kept exploring possible options.

In 2010, Cobb received a yearlong research assistantship at the Harvard School of Public Health in Epidemiology. While at Harvard School of Public Health, she says she had noticed the people with higher degrees were doing the more interesting and in-depth work.

In the final analysis, experiences gained at Stony Brook and Harvard served her well, becoming a key motivator. Rather than stop with one graduate degree in hand, Cobb sought the opportunity to do the most challenging work possible and persisted in finding the right institution.

Ultimately, Cobb decided to enroll in the doctoral program at UGA. This was a return to her home state, and to a place that felt welcoming and inclusive.

While choosing the school was not a difficult decision, it was still one she analyzed deeply. “UGA offered me a fellowship,” she says. “And the reason I chose my specific department was that I noticed my failures at Stony Brook and I wanted to be sure the fit was good, that it was research I was interested in, that the faculty was inclusive, diverse. UGA seemed like a good fit.”

On the Georgia campus, Cobb says she found the optimal situation, just as she had sought.

The ideal fit at UGA was due to several factors, she explains. Those factors included the presence of “more women faculty, and more diversity.” She was in the company of scholars that she admired. “I was not the smartest,” she insists modestly. But she had found a strong peer group, and she also found a sense of academic fraternity in Athens.

“When I was struggling, I had the support of faculty to work harder,” she stresses.

Adjusting Her Sail

“A lot of African Americans shy away from STEM disciplines, as if it is not for them,” Cobb says. And yet Cobb had long known that STEM was for her. She had whipped through undergraduate school at Savannah State in three years, earning a bachelor’s degree in mathematics and a minor in biology and taking top honors. She began her academic career in mathematics, but her undergraduate advisor at Savannah State had influenced her to enter statistics when she first applied to graduate school.

Statistics simply suited her. “Once I got a grasp of it, I realized it was for me. When you think of math, you always think about theory,” she explains. “But the stats drive the picture!”

During early days of graduate studies, Cobb quickly learned that she wanted to do her own research. She also found that she was drawn to the area of public health. For her, becoming a biostatistician was the synthesis of all her interests.

When she found herself back in Georgia, she enjoyed the more relaxed, kick-off-your-shoes-and-get-to-work atmosphere in her collegial department. Cobb settled into her future dreams, which were now coming to fruition. When she received her doctoral degree in May of this year, it was cause for a huge family celebration. “Maybe 20-25 people were at my graduation!” she exclaims.

They were there to celebrate the deep happiness of Cobb’s achievement. Their family ties run deep. Cobb reveals a tiny tattoo she had done in order to honor a seven-year-old relative who died of cancer. Eric Shaw Jr. was his name. The tattoo became a permanent reminder of his struggle.

In so many ways, Cobb has made the lessons gained from pain and adversity her strongest ally.

“Take what others perceive to be as your deficits, turn them into your strengths, then go and conquer the world,” she writes in an email. Later, she sends two quotes as a postscript:

“She stood in the storm, and when the wind did not blow her away, she adjusted her sails,” by Elizabeth Edwards; and another by W.E.B. Dubois, “There is no force equal to a woman determined to rise.”

These are her mantra.

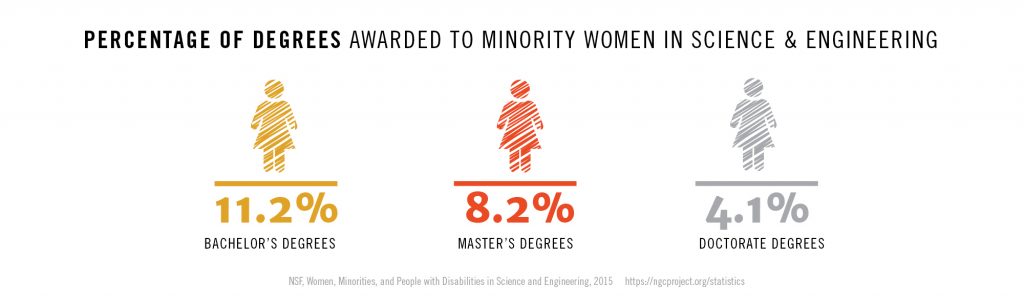

Compelling Statistics for Women in STEM

In 2012, only 11.2% of bachelor’s degrees in science and engineering, 8.2% of master’s degrees in science and engineering, and 4.1% of doctorate degrees in science and engineering were awarded to minority women.

NSF, Women, Minorities, and People with Disabilities in Science and Engineering, 2015, https://ngcproject.org/statistics