Victoria Jackson

Jackson’s private life held tremendous impact, shaping her deepening interests in human services. As a survivor of intimate partner violence, Jackson has come to understand adversity in a very personal way. Her career path reflects a humanistic focus and an evolving series of self-determined challenges.

By: Cynthia Adams | Photos By: Nancy Evelyn

Victoria Jackson, looking justifiably pleased, describes having spent six days during the winter break experiencing the culture of Costa Rica completely on her own. She looked refreshed and pleased, despite having navigated a foreign landscape equipped with rusty Spanish, no guide, and patchy Wi-Fi. Also, she had found herself locked into a physical test high in the wildly beautiful terrain of Costa Rica’s rain forest—one she initially regretted, but later enjoyed.

She had passed an important test in self-reliance. The UGA scholar had successfully dodged all the scariest outcomes that might have sabotaged her independent foray into the unknown.

Jackson emphasizes that she likes testing herself by moving outside her comfort zone. She seeks new experiences. And also, she likes being an independent thinker and woman. Costa Rica offered a trifecta of challenges—yet all offered a happy ending.

This spring, Jackson completed a Master’s degree in Public Health with a concentration in Health Promotion and Behavior. Her research interests concern disparity of health care for women. She says interests in “maternal health, prenatal care, and social support in minority women,” have fed into her much larger dreams of being “a change agent in women’s health.”

Usually she puts herself together in polished clothes and wears signature pearls. But after returning from her most recent self-challenge, Jackson wore athletic wear, reflecting a grand adventure abroad undertaken alone.

She was still relishing having faced down a few fears (chiefly daunting heights, diabolical spiders and Day-Glo colored snakes) in order to zip line in the Costa Rican rain forest of Monteverde, explore the city of San Juan on her own, and—importantly—not step down from the call of adventure.

Instead, Jackson stepped right up.

The trip was a good beginning to 2019 for Jackson, who savors travel and celebrates important milestones by venturing to far flung destinations.

“I’d prefer not to discuss the spiders there, though,” she jokes.

In finding her professional footing, Jackson has had many important professors who also became valued mentors. She names several from her undergraduate days back at the University of South Alabama where she studied healthcare management and communications, and now two important mentors at UGA. Andrea Swarztendruber and Grace Bagwell Adams are first in mind.

Swarztendruber, an assistant professor of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at UGA, is a primary influence. Jackson has been working under the professor whose areas of expertise include sexual and reproductive health, adolescent health, maternal and child health, and women’s health policy.

“Dr. Swartzendruber does all these women’s initiatives. She’s a real life trailblazer,” says Jackson with clear admiration for her mentor.

“I didn’t realize how famous she was until I was assigned to her as a research assistant,” she confesses. “She is (widely) quoted in national research publications.” Swartzendruber contributed to the Georgia Abortion Fact Sheet, as Jackson points out. In her research reviewing biostatistics and data for that project, Jackson learned about issues pertaining to women’s reproductive rights. It was a revealing experience that has sharpened her career focus.

“I might stay in Georgia and just come back and work under her,” Jackson says. The professor’s impact has been that strong, she emphasizes.

Swartzendruber created a database with a two fold goal: assisting individuals seeking health services to discern which clinics actually provide crisis pregnancy services, and facilitating academic research related to clinics providing crisis pregnancy services.

Adams, an assistant professor of Health Policy and Management at UGA, is another faculty member whose influence is significant for Jackson.

She writes that she “focuses upon vulnerable populations and the policy responses to mitigate that vulnerability.” This work speaks directly to Jackson’s graduate thesis.

Ranking at the Bottom: A Stunning Statistic for U.S. Healthcare Reveals a “crisis of death and near death in black mothers”

Jackson’s research area concerns maternal care for black women, particularly as affected during natural disasters and other highly disruptive events such as hurricanes. Jackson says it is a case of vulnerable populations made even more so by the experience of extreme situations.

The disparity between those most and least vulnerable during natural disasters has caught the media’s notice. In the past year, there has been extensive reporting on the radical differences between white and black pregnancy mortality/survival rates.

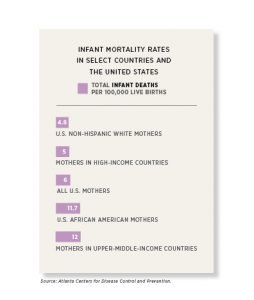

In February, the New York Times published a staggering fact. The United States now ranks 32nd out of the 35th wealthiest nations for infant survival rates.

The ranking is driven by “the data for black babies.”

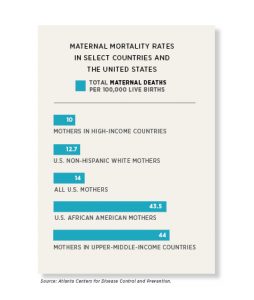

The NYT’s report also underscores a twin tragedy to high infant mortality, which is maternal mortality: or, as they state, “a crisis of death and near death in black mothers themselves. The United States is one of only 13 countries in the world where the rate of maternal mortality—the death of a woman related to pregnancy or childbirth up to a year after the end of pregnancy—is now worse than it was 25 years ago,” the report adds.

- Photo Courtesy of Victoria Jackson

Jackson with two young friends at the library, left, and with her sister Katie, center. Katie Jackson is a UGA undergraduate majoring in Journalism. She is also a member of the UGA track team. At right, Jackson shown in her zip lining gear in Costa Rica.

Citing data reported by the CDC, the article stated that black women are “three to four times as likely to die from pregnancy related causes as their white counterparts.”

Jackson’s research will specifically focus upon that same target, in considering those exposed to unusually high threats of extreme situations. “My thesis will only address those risk factors of maternal mortality as they correlate with hurricanes and natural disasters,” she explains.

In her thesis work, Jackson considered affected populations in Virginia, North Carolina and South Carolina. Those areas offered significant disaster data. During the period 2016-18, the United States experienced 19 hurricanes. The burden of evacuations alone, Jackson reports, created undue stress for those affected, and is reflected in infant and mortality survival rates. She also explored pregnancy and parenting data specifically during Hurricane Florence, and analyzed the storm’s effects on maternal and caretaker’s health.

In late March she had completed her research.

“Social support was negatively related to stress, meaning the higher the level of stress the lower their social support,” Jackson reports.

“We also found that respondents with high income were more likely to have access to people who could assist them in a financial emergency.”

She described how the researchers gathered data.

“We had some open ended questions about how did they prepare and asked if there were anything else they wanted to share. One of the respondents talked about how hard it was driving with an infant and a toddler alone, and another respondent lost her entire house and had to move to California for help since her husband was overseas for the military.”

Many of the respondents in Jackson’s study live near military bases, and in storm prone areas. With extreme weather on the rise, ever larger numbers of mothers, caregivers, and infants are potentially affected.

Is the lack of good maternal care a case of a deeply worrisome problem indicating too few public health initiatives? Jackson says yes.

“Plenty of articles state that maternal care is a problem, that it is not as good as it should be. But no one is developing programs from the research to improve these problems. We do have Healthy Start. But not only low-income women need help. “If they added more of a social support component from outside, I think it could be much better.”

She adds, “When you look at women’s rights, we have much to do. Women are supposed to be so strong. Viewed as, if you can give birth you can do anything. And women are also the caregiver of the house as well. When you look at the norms, and think about the role of a woman in any family, they are already kind of tough. And stressful. And when you add on the stress of having to take care of your own health—and I know because I’ve talked to a lot of women—that is not what they’re thinking about. They don’t care about it (self-care) because they have to take care of everyone else in the family.”

Jackson’s interests in “maternal health, prenatal care, and social support in minority women,” have fed into her much larger dream of being “a change agent in women’s health.” Jackson’s future research will expand upon women’s health initiatives. Shown at left, an Athens resident in her third trimester. She safely delivered her child this month.

Expressing Vulnerability in Order to Lend a Helping Hand

Jackson approaches the next phase of her career and life with all options open after completing a graduate degree. She plans to take some time out of academia and work first, while considering a return to doctoral studies, or even the possibility of beginning an entirely new career. Yet her primary interests seem to fall within the realm of society’s most vulnerable, and the impact of adversity.

Jackson was tapped to attend last year’s Emerging Leaders program, which is offered by nomination to select graduate students through UGA’s Graduate School. She was one of only 14 graduate students chosen for the training experience, and referred by faculty.

During the Emerging Leaders three-day program in Dillard, Ga., she shared that she had personally experienced partner violence. Pushing through this, Jackson explained, was indicative of her personal strengths. She described painting and creative projects, outlets she uses to reinforce those strengths.

She draws from the past, Jackson adds.

Among Jackson’s most important jobs during her undergraduate years “was working with 12 kids at the local YMCA.” This life changing work “planted the seed to become a public health professional,” she explains. She did not shrink from difficult projects. Immediately following her bachelor’s degree, she accepted a position teaching sex education at a youth detention center.

As her interests have expanded while at UGA, Jackson is now interested in future research regarding women’s health. She has focused upon nonprofits as career possibilities. This spring she became a Fellow at the Atlanta Feminist Health Center.

Her sole sibling and younger sister, Katie Jackson, is near and dear. She is a UGA undergraduate majoring in journalism. She is also a member of the UGA track team, a point of pride for the older sister who enjoys watching her compete. The sisters are from Auburn, Ala., where their parents are educators and excellence was encouraged at home.

Telling Her Story and Creating New Ones

Today, Jackson talks about how much she values effective storytelling as a way of further growth and exploration. And, she says she enjoys learning more about semantics and self expression in general. “I like dialogue, because it helps me prepare my arguments.”

She says she has grown through her coursework and professors, and has come to value challenging long held ideas about everything, including hot button issues such as politics.

“But I do like to listen…just so I can have my arguments ready,” Jackson jokes, having a good laugh.

During her Costa Rican holiday, Jackson had to put all her communication skills to the test. Although her spoken Spanish was rusty, she pushed herself into the unfamiliar and found ways to communicate. In the course of the holiday, she not only kept the promise with herself to experience the zip-line alone, but ventured out on the town to experience a holiday parade. She sought out museums, cultural experiences, new foods, and beautiful beach vistas.

But she confesses there were bumps in the road. She was ripped off by an unscrupulous Uber drive while sightseeing and had to walk miles back to town to the hotel. Lacking Wi-Fi or GPS access, it was a perfect storm of vulnerabilities. Feeling underconfident about her spoken Spanish and unsure about seeking direction, Jackson still persevered and made her way back.

Rather than souring her adventure, it became a personal triumph. There was a sweet end note, when hotel staff insisted that she go out on the town with them—which completely redeemed the experience.

The staffers told Jackson they wanted her to leave Costa Rica with a happy memory.

She says she left with too many to count.

- Source: Atlanta Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Source: Atlanta Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.