This is Not Your Grandpa’s Classroom

By: Cynthia Adams | Photos by: Nancy Evelyn

If there is a shared belief among these teachers, it might be this: Blaze new trails.

With Clickers not Chalk: Five Excellence in Teaching winners find innovation and success thrive best when there’s equal room for failure and originality.

What do five award winning educators have in common? Try everything and nothing.

The classroom of their collective dreams allows for failure as much as success—after all, failing faster and better is the surest pathway to learning. (Ever heard the adage that one person’s breakdown is another‘s breakthrough?) And then there are the tools. In the now distant past, a slide projector and white board were the best available. That was then—long before smart phones, personal computers, and tablets.

These technologically advanced tools, packing more computing power than a 1980s-era data center, are handily at their students’ fingertips. Some argue this works for the good, others say they are distractions.

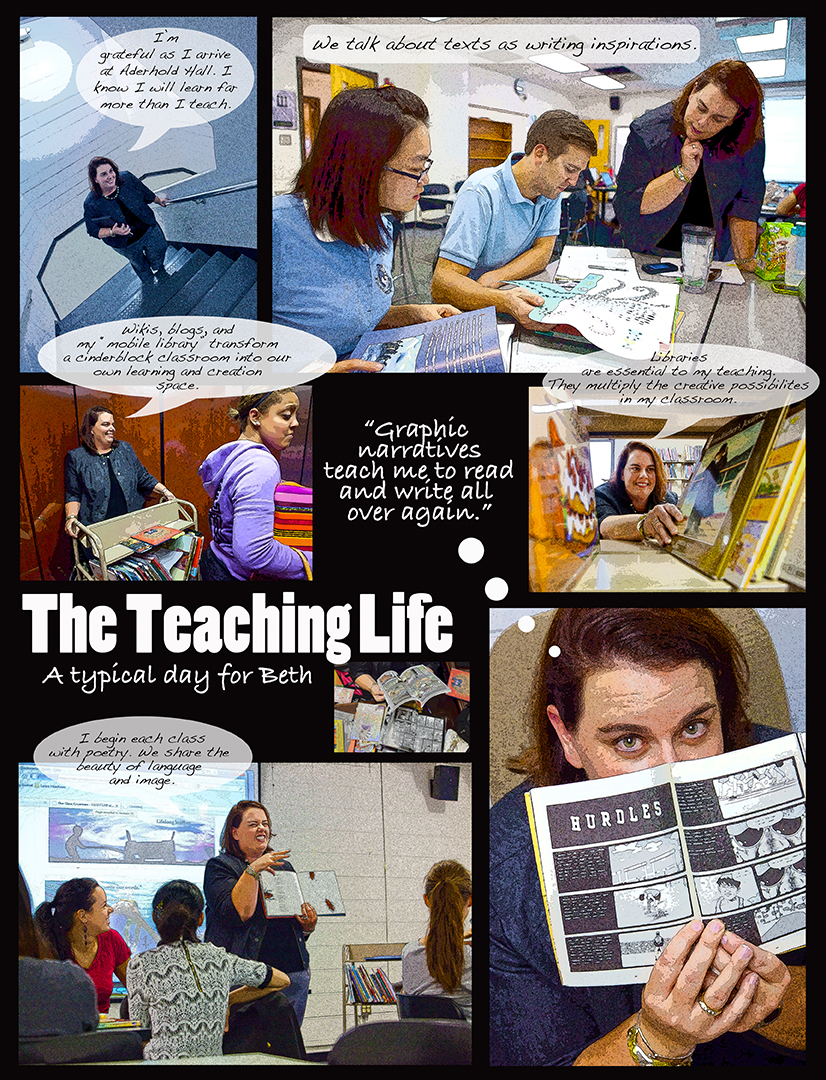

But in the end, the educator’s energies fuel the classroom. Then there’s something else: Risk-taking and daring. They all possess that. They run the gamut of experiences and passions, including running a writing center (Beth Beggs.) Dana TeCroney grew up on a dairy farm in New York, and formerly drove a race car. (He later rolled into Georgia behind the wheel of a Cadillac.) But he’s also a sometimes Luddite who believes a roll of the dice or sidewalk chalk are dynamic teaching tools. Another (Beth Freise) believes the best way to arrest a student’s imagination just might be through a graphic novel.

Joseph Pate holds to the value of experimental education. Michael Amlung has worked with gifted middle and high school aged students through the Duke University Talent Identification Program at UGA.

These five University of Georgia doctoral students, recently awarded the Excellence in Teaching Award, honor the unique spirit of learning. They reflected on what they are learning inside the classroom. Michael Amlung, Beth Beggs, Elizabeth Freise, Joseph Pate and Dana TeCroney then reported back from the front lines of education.

Michael Amlung is a doctoral student in psychology. He has been both a teaching assistant and instructor for various psychology courses.

Can innovation be nurtured? Amlung says “Yes!”

Ask him “How?” and he says by taking chances and allowing for do-overs when the first idea fails.

Did You Know That Education Can Click?

Forget blackboards and chalk. Amlung uses a wireless device known as “clickers” in the classroom.

“These wireless handheld response keypads allow students to respond to questions posed by the instructor, and the class can view the results in real time. This is especially helpful in psychology, since many of the topics we discuss are sensitive in nature. Students may feel more comfortable providing their opinions using an anonymous keypad than having to raise their hand in class.”

As a scientist, Amlung teaches students how to parse out Internet fiction from fact. They begin with a published article.

“One challenge that I face as a scientist and researcher is when the findings of scientific research are misrepresented by popular media sources. For obvious reasons, news media is always looking for the hook to snare readers and increase ratings, but we have seen many examples of empirical results being taken out of context or generalized far beyond their original intent.” So, Amlung challenges his students to evaluate a journal, magazine, or Website article.

“One strategy that I use to build these skills is by having my students read a news story that presents the results of a psychological research study. Students are asked to identify the main conclusions and implications of the study based solely on what is presented in the story. I then provide the actual peer-reviewed scientific journal article and ask my students to compare and contrast the conclusions and implications drawn from the primary source with those from the news article.”

Also, Amlung developed a virtual conference for his students via TED.com, allowing them to choose topics they wanted to learn about. (TED stands for technology, entertainment and design. It is a project offering online information via the Web site).

“My students viewed a series of short TED talks by prominent psychologists and wrote brief commentaries that required them to extract the main ideas, identify concepts they found particularly interesting or confusing, and critically evaluate each speaker. Students then wrote a reflection paper in which they synthesized the overlapping themes in the lectures.”

Beth Beggs, 2012 Graduate Student Teaching award, photos taken with grad student Kristen Cameron (lab coat) as a play on words “writing lab.” Beggs in assistant director to the writing center at Parks Hall on campus.

Beth Beggs is a doctoral student studying English in the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences. She has been an instructor and also helped reconfigure the UGA Writing Center. When she talks about creativity, she employs musical metaphors and doesn’t stop at convention.

Beggs sees creativity “as the appearance of new ideas,” and views it as the responsibility of higher education to support and advance original thinkers.

“Think of Carlos Santana’s Supernatural CD. When Santana records with Everlast the edge is sharper. With Dave Matthews, Santana’s slow riffs are even smoother.”

She isn’t convinced technological advances threaten creativity, saying even the lowly pencil was once viewed as innovative technology, “but humanity remained and advanced as a creative, analytical, and innovative creature. Therefore, I recognize the power of technology to stimulate creativity.”

Beggs says certain technologies (admittedly low-tech ones) are actually helpful to her as an educator. Which things?

“I love the little things like strong Internet connections, a laptop, and a classroom projector. Online journals and books give my students access to scholarly articles that a brick and mortar library couldn’t afford to provide in hard-copy. A projector allows me to do pedagogically what I ask my students to do in their writing: ‘Show me; don’t tell me!’”

Beth Friese is a doctoral student in the College of Education. Friese has taught multiple classes in the Language and Literacy Education Department over the past three years. She incorporates technology and graphic novels into the curriculum.

She suspects students need a push to become creative thinkers. “This concerns me for two reasons. First, I think that creativity is important in our endeavors to solve society’s most pressing problems. Creativity needs to be nurtured as often as possible. Second, most of the students I work with are future educators. If they are not asked to be creative in classrooms, I suspect that they may be less likely to ask their own elementary and middle school students to do creative work.”

“Multiple-choice thinking” worries Friese. “In our class meetings, I provide lots of opportunities for tinkering and playfulness as we work. They learn new tools and create when the stakes are low and the level of support is high.”

When she gives students an assignment, Friese tries to leave it as open-ended as possible. “But, I tell them that there won’t be a devastating penalty for trying something completely new and different. Instead of just trying to replicate an example, I want students to think for themselves. I want them to puzzle through problems.”

She thinks the discomfort leads to something extraordinary. “Some of the best learning happens when students are a little bit uncomfortable. It happens when they stretch themselves, acknowledge their own limits or blinders, and then overcome them, often brilliantly.“

Friese takes a cue from one famously creative company. “Inspired by Google’s practice of giving employees 20% of their work time to pursue personal projects, I recently started reserving a portion of my courses for students to pursue educational goals that they select for themselves.”

Joseph Pate is a doctoral student in the Department of Counseling and Human Development Services. Pate has instructed a range of courses and also co-facilitates a graduate course on Experimental Education.

He believes dynamic things can happen, especially in the “pauses”.

“As a recent graduate from the field of leisure studies, much of my inclination is that true innovation and creativity comes from moments of reprieve from the structures we find ourselves bound within. Of course in our work-centric culture, to choose time like this or find ourselves in times like this, we are met with cultural norms that tell us we are wasting time. However, it is within these pauses where, at least for me, things shift, happen, arise, and/or emerge that tend to be the seed or catalyst to some of my most creative or innovative thoughts.”

Pate believes young folk today are as innovative as he and his classmates were. With one codicil.

“…the simple answer is they are just as creative as me and others,” he argues. But he thinks the present-day pressures to perform on standardized tests are contrary to creativity. “Growing up, we had a few standardized tests we had to take at certain grade levels, but the current ‘teaching to the test’ and the constant and elevated focus on end of the year markers which schools now use to secure funding, resources, and personnel, have changed the landscape of traditional and dominant k-12 education. What I experience is many students are so use to being taught to achieve/perform on a test that they are not asked what they think. And asking what someone thinks is the foundation for creativity or innovation.”

Pate has mixed feelings about technologies. The people he regards as creative “spend exorbitant amounts of time thinking, writing, playing, working, musing, and tinkering with ideas, thoughts, feelings, and emotions. They also seem to tend to pay attention to a lot, observe a lot, and notice a lot. And in doing so, they draw connections where others did not see connections. This is one of the greatest parts of innovative or creative thoughts – connections or bridges between things that in the past seemed divergent, distinct, separate, but that actually may fit together or help things make sense in cool and different ways. I just wonder if that is what technology is taking us away from.”

Pate’s philosophy is more experiential. “I want the learning that occurs in my classroom to be situated within and from the learner as they engage with content, not predicated on what I think the learning should be. To be honest, this is some of the trouble I have with learning outcomes – I find it hard to know what learning will occur because every student and context is different.”

So he would love to banish grades altogether. “The biggest challenge is gaining the trust of students that they can explore, fail, and still be successful. Failing is equated to failure, which in turn is equated to failing in some formalized and systematic sense with regard to grades, GPA and a perception that this will then detract from their ability to be successful.” A dramatic scene in a film about an innovative educator captivated him.

“I liken the whole thing to the scene in Dead Poet’s Society where Keating is having the class walk and points out how naturally everyone begins walking in rhythm. He then inspires them to walk at their own pace with their own rhythm, and one student is called out for not marching. This student states that he is practicing his right NOT to march. He is immediately reinforced by Keating for truly understanding the spirit and nature of the activity. That is learning. That is innovation. That is celebrating and bolstering an empowered and creative perspective on the whole mystery of education and learning. It is not about what someone does based upon what others are doing, it is getting at a more cored, essencing spirit that captures thought, agency, and assertion of self in relation to learning and growth.”

Dana TeCroney is a doctoral student in the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences. He is a mathematician, and has taught at various levels.

“In the 1980s there was a movement in mathematics education that focused on the development of skills (think about memorizing multiplication tables) versus the structure of mathematical ideas (think about representing 3 x 4 as 3 + 3 + 3 + 3, 4 groups of 3, etc.). One large impetus for change was finding a balance between these ideas and another was the availability of technology.”

From slide rules to calculators, how did mathematical education change? “As calculators became more mainstream in schools, there was less of a focus on computations and more emphasis put on problem solving, representing mathematical ideas in different ways, and seeing connections between different representations. These changes suggest that there is more room for creativity and individuality because they encourage us to look at problems from a number of perspectives. In other words, we are trying to get away from a model where the teacher stands in front of the room and does a problem and then the students do three problems just like the one the teacher presented. One challenge to changing instruction in schools is that we are asking people to teach in ways that are different from the way they were taught, and in many cases, the way they learned to teach. Another challenge is that the mathematics in schools today is different from the math in schools 25 years ago, so support for change from the public (parents, administrators, politicians, etc.) has not been tremendous.”

TeCroney says students today are also as different as 1980s mathematics instruction.

“When Al Gore was vice president many people thought it was laughable when he made a speech and said that every classroom in America should have a computer and be connected to the Internet. Now children who are less than 10 can operate a computer. Nearly every student also has a cell phone and most have a smartphone. Students have a tremendous amount of information at their fingertips, which has drawbacks and benefits.“

A student can always seek help online; the problem is, it inculcates the notion of instant resolution, TeCroney observes.

“The expectation for instant answers is challenging for mathematics teachers because it is a subject where looking at the same problem using a number of approaches can lead to different results and give different insights. Mathematicians also value false starts because sometimes we can learn as much from a wrong approach as one that leads directly to an answer.”

TeCroney underscores mathematics having had an undeserved bad rap, saying, “For many people, mathematics is viewed as a subject where there is a right and wrong way to do things and there is one correct answer. There is a set way to solve different types of problems, and being successful in math depends on remembering the procedures you have to follow in order to arrive at the solution. Plenty of factors contribute to this view, many of which related to the way mathematics has been taught and the resources available to educators.”

Dana TeCroney, PhD candidate studying math education – winner of the 2012 Graduate Teaching Awards