The Charm of a Mule Barn: Double Dawg Scott Messer The Unlikely Saga of a Mule Barn, a Double Dawg Preservationist, a Texas Rancher’s Son, and a Community United.

By Cynthia Adams | Photos by Nancy Evelyn

Scott Messer, possessed of a strong jaw and a willingness to pull a heavy load, is stubborn. Not as stubborn as a mule, not quite.

Yet the preservationist is doggedly determined when it comes to rescuing historic buildings, including a concrete 1920s mule barn on the Griffin campus. (Yes, you read that correctly. It is a concrete construction.)

The barn reopens this year as the Dundee Café—made possible by the Dundee Community Association.

“It was all privately funded—doesn’t have a University dime involved,” says Messer. And he gives a hint of a smile—not a mule-eating-hay grin, but just enough to register sanguine pleasure.

Then he says, “Call Lew.”

Lew Hunnicutt, assistant provost at the Griffin campus and campus director, was phoned.

It was all true. A quirky barn once slated for demolition had found a dogged champion in Hunnicutt. Messer was aware of the barn as the second oldest building on the Griffin campus. He wanted it to survive. But to make it usable would require significant money—money not easily found.

Hunnicutt, determined this barn needed to remain intact—in fact, better than intact—jumped right in, taking it as a personal challenge.

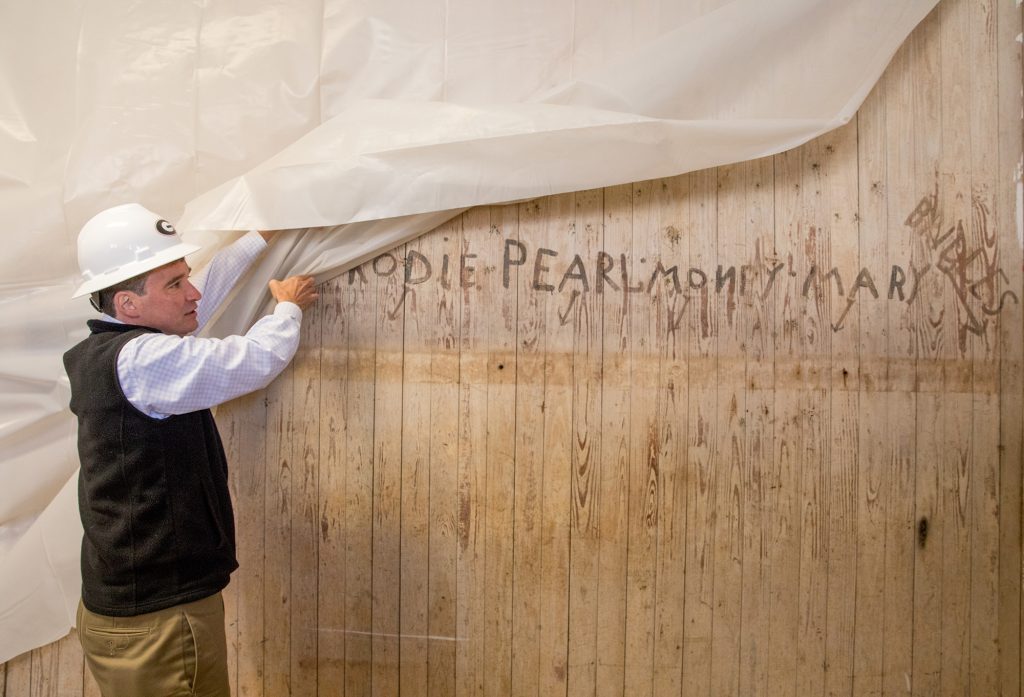

The Texan drawls, “There’s history written on the walls.” In actuality, the mule’s names are penciled on the boards inside, along with various calculations that were scribbled onto the walls by farmers long since gone.

At first, Hunnicutt says, “I didn’t realize it was a barn.”

And small wonder. Improbably made of concrete, the clunky looking building wasn’t anybody’s notion of a traditional barn. Hunnicutt found himself in possession of a key and soon after he was hired began visiting the barn from time to time.

Others before him had hoped it might be restored and repurposed. But it languished, full of stored items long forgotten.

“When I first got here, somebody told me it was once supposed to become a café,” he says.

To a recent transplant from a small Texas town, the mule barn seemed emblematic. As a rancher’s son, a barn was where Hunnicutt could step out of his administrative role and settle his thoughts. The mule’s names scribbled onto walls with a pencil stub made the barn’s history real and appealing.

The future of the mule barn was settled, at least in Hunnicutt’s mind. It offended his practical nature to watch the building decline as unwanted items moldered inside. As the man in charge of facilities on campus, he took a first step, signaling that its status was changing. Hunnicutt asked that the barn be cleaned of all the forgotten detritus—if nothing else, it would make others view it differently.

He dangled a carrot, promising that in return they would host staff birthday parties and events there once cleaned.

Scott Messer is charged with the oversight of historic properties owned by the University. He stands inside an historic barn at the Griffin campus, which is the second oldest existing building there.

Just clearing out the junk had a good effect.

All artifacts were kept. At least 38 various items, including mule shoes, wagon pins and pieces, were preserved for display on site.

Meanwhile, Hunnicutt added touches of Texas and Griffin history to his office; he brought in an 1860s era field desk he had painstakingly refinished, and mounted Texas longhorns on the wall. Historic sepia photos of Griffin went on display, showing the former bleachery and nearby mill.

Mule History

By 1808, the U.S. had an estimated 855,000 mules worth an estimated $66 million. Mules were rejected by northern farmers, who used a combination of horses and oxen, but they were popular in the South, where they were the preferred draft animal. One farmer with two mules could easily plow 16 acres a day.

In 1909, UGA’s Monthly Bulletin listed a total of 15 head of work animals owned by the College farm. “These mules are of superior excellence, and represent different types, including medium heavy plantation mules, sugar mules, and heavy draft mules.”

http://www.mulemuseum.org/history-of-the-mule.html

Catalogue of the Officers and Students of the University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, University of Georgia, January 1, 1909

Hunnicutt amassed a collection of cat’s eye marbles in a clear glass jar, along with other artifacts and mementos, creating his own cabinet of curiosities. The office, a former lab, revealed a sense of history.

“Dundee Mill stood across the way,” he says, looking out an office window. “Griffin was a big mill town. Dundee towels (once produced there) are a big thing.” He discussed the barn with Messer, frequently in Griffin on another project.

Around 1920 the original mule barn burned, and when rebuilt it they used slip-form construction technique, Hunnicutt learned.

He felt triumphant when he discovered a way to make a barn renovation financially possible—having persuaded a local donor and restauranteur to provide restoration funds. All the funds.

Then the donor died suddenly in a tragic accident. Hunnicutt promised himself he would find another way. He did—this time, successfully persuading a community group to donate the funds.

“As the second-oldest structure on campus, the mule barn represents a part of Georgia Experiment Station and University of Georgia history that will be preserved and cherished thanks to the generosity of the Dundee Community Association,” Hunnicutt announced in a news release.

Before Hunnicutt broke down a detail-relishing, what-are-the-odds-of-that account of events surrounding the revival of the mule barn—which is reaching the end of its transformation into the brand-spanking-new Dundee Café—he talked about the rehabilitation.

That, he said, was all Messer.

“I will take credit for finding the money,” Hunnicutt said, as Messer listened, “but I give him all the credit for the vision.”

And here’s what Hunnicutt revealed about Messer: Messer possesses a much more useful trait than talent. He is persistent. And—bonus—he is an historian. Hunnicutt says the words with clear admiration.

Preserving Hundreds of Historic Properties

Messer is already a double Dawg, having earned undergraduate degrees in history and political science from UGA, and a master’s in Historic Preservation in 1996. He consulted in private practice before joining the faculty in the College of Environmental Design and becoming the campus preservation planner on November 16, 2000.

The historian in him noted the date on a calendar on his office wall. It remains there, “to remind me when my 30 years are up,” he jokes.

He crisscrosses the state of Georgia as director of historic preservation in the Office of University Architects. At any given point in time, Messer may be overseeing as many as dozen projects. The mule barn is only one. “Over half of the UGA properties are historic,” he says. “Over 743 of the buildings in the inventory are more than 40 years old. We put a lot of money into preservation. We’re constantly doing that.”

He is also a doctoral student in environmental design and planning, and freely admits he is unsure when he will complete his doctorate because his desktop groans with work projects he manages, including a 742-page master historic plan for the entire University.

Messer’s brows shoot upwards at the question of completing his dissertation, pointing to a heavy stack of papers in his UGA office—his academic research, which could fill a small box.

“There it is,” he says.

Since taking his position, Messer has received so many awards for his preservation work that even his short CV is six pages long.

Also—according to one who knows him well—Messer is technically adept, pragmatic and driven. But he is also skilled at finding ways and means to execute ideas, says Pratt Cassity, who recently retired as the director of the Center for Community Design and Preservation where Messer was a graduate student in the late 1990s.

Dundee Mills

The Dundee Community Association donated over $1 million to restore the Mule Barn—money raised from years of vending machine proceeds and bake sales, with only a single request: that the restored Mule Barn bear the Dundee name. The Dundee Café will host community events and feature rotating exhibits on the history of the campus and surrounding community, including the nearby Dundee Mills, pictured above. Pictured below: Dundee Towel Ensembles 1948 Ad. http://www.spaldingcounty.com Photo By: Peter Farrar – dsfdawg

“It has been so rewarding to see Scott Messer move from the pony-tailed student with guitar case sitting in the back of my class, to a committed graduate research assistant in my office who worked on a national rural preservation grant from the NEA,” notes Cassity.

He has followed Messer’s career since, as their professional lives frequently intertwined. After Messer completed his master’s he moved to Louisiana with Jennifer Messer, his spouse, who then worked in historic preservation. (She is now the development officer for the College of Environmental Design.)

Cassity adds, “I worked with him then as a trusted colleague in Mississippi and Louisiana. We worked side by side with staff from the Stennis Small Town Center at Mississippi State University and the Louisiana Main Street Program on the states’ small-town character conservation issues. Finally, to spend my last years before retirement following his lead here on campus as we got the UGA preservation plan ready for rollout has been a satisfying educational cycle for me to complete as a teacher.”

With the 742-page master plan recently completed, Dean Dan Nadenicek presented Messer with the Dean’s Award in April.

He has been recognized for outstanding rehabilitation projects so often that it is tempting to equate him with Meryl Streep and Oscars—his name is going to be among the first mentioned for talent and momentum.

“His willingness to make things work efficiently without fuss or frills is a great skill I admire (and don’t always exhibit)” says Cassity. “His style accommodates wry and workable solutions. I appreciate that we have learned together how things work for and against historic preservation. Some very obvious institutional processes make sensitive rehabilitation less probable at a large University, while the long traditions and sentimental attachment to place make it much easier to save buildings here. Scott uses both those realities to smoothly execute his state-mandated built environment stewardship role at UGA. It is a tough job that seems tailor-made for Scott’s talents. In short, he rocks, he cares, he’s making a difference.”

All artifacts—saved for later display—were kept. At least 38 various items, including mule shoes, wagon pins and pieces, were carefully preserved for display on site.

A Barn That Ought to Remain a Landmark and a Community that Agreed

When Messer met Hunnicutt, he was already keenly aware of the mule barn. He had a special weakness for barns.

The mule barn at Griffin was technically important, as all agreed. Once a demonstration project for poured concrete at the time that the Griffin campus was a research station, it was at the very center of the campus. Eyesore wasn’t quite the right descriptor, but homely was a kindness. As barns go, the mule barn was unbeautiful.

Many thought it was just a bad use of land. But others, especially Messer, differed.

“This building was part of a demolition package that came out of the School of Agriculture for space clearing. Through the environmental review process, this was a handful of buildings they needed to retain. We held onto it but didn’t have a use for it.”

The barn was spared from the wrecking ball, but it languished.

Every time Hunnicutt walked across campus, he stopped at that barn, thinking. The barn key was always in his pocket. “The vision for the mule barn wasn’t mine,” he insists, “but it had been neglected…” Neglect bothered him.

“Lew was hired, and he took a shine to the building, and said he had a vision for it,” says Messer. “Lew really drove it. At the time, I was working on a project building a food product kitchen.” The two men got to know one another. Like any good team, both give the other credit.

The cost to save the mule barn had been calculated some time ago at $1 million. Updated figures were sure to go even higher.

“I approached the provost, my boss,” says Hunnicutt, who resolved to find a path to saving what amounted to a white elephant. “She said, it’s a fantastic idea but you’ll have to raise the money.”

The Texan took the challenge. It was Griffin’s white elephant. A couple of months later, Hunnicutt showed the barn to another person representing a charitable foundation. The charity was endowed by former employees of the defunct Dundee textile mill, which employed 4,000 in 1995. The mill had once stood within a stone’s throw of the mule barn on Griffin campus.

Hunnicutt learned that the Dundee Community Association had several million in principal and had decided to deplete the principal. The enterprising group raised money via bake sales and vending machine profits while the mill was still operative.

“Back in the 1930s, they put together the Dundee Community Center. The board that ran the Dundee Community Association were all former workers or managers. The mill owners invested in education for their workers and had this history of wanting their mill workers to do better. They merged with Springs and became Dundee Springs. Then, the mill closed,” Hunnicutt explains.

The Dundee Community Association were the alliance Hunnicutt sought. They consented to fund the project in its entirety with over $1 million in gifts. Hunnicutt provided $50 out of pocket. But he needed a vision, a plan.

A nearly 100-year old mule barn on the University of Georgia campus in Griffin, Georgia will be repurposed into a cafe that will connect students and the surrounding community with the history of Griffin and Spalding County. The 3,900-square-foot Dundee Cafe at the Mule Barn is scheduled to open in Summer 2018 in the historic structure near the campus student learning center. Photo By: CAES – UGA

Cue Scott Messer

“We heard about it, that Lew might have a donor,” says Messer. “Then, we did a study for costs with a local architect.” All parties agreed to keep impact to a minimum. As Messer says, the ideal “is reuse.”

The community benefactors and Hunnicutt both agreed to adaptive reuse. The concrete barn would be repurposed but intact.

Messer couldn’t believe that with a multitude of projects listed, all wanting his attention, one had found happy convergence in Griffin, thanks to Hunnicutt’s remarkable community group.

“We’re kindred spirits on renovating and protecting it,” says Hunnicutt, nodding to Messer. “But it took us 13 months to get the kinks worked out.” The biggest kink involved getting a firm price for the restoration.

“Lew gets it,” Messer says. (He, too, has a weak spot for barns.) “This is one of my favorites, and a cattle barn at Skidaway, an octagonal barn built by the Roebling family,” Messer adds, standing inside the barn as construction began in March. The 3,900 square foot Dundee Café at the Mule Barn opens this summer.

Backhoes prepared the way for a new outdoor seating area at what is the barn’s entryway. Workmen stood on lifts prying rotting wood from the upper story. Messer, in hardhat, watched despite a cold March wind.

“This is my favorite project,” he admitted, blue eyes intent as the backhoe chewed up chunks of concrete and equipment whined.

Two allies had scored a win-win. “Reuse of this as a core resource, and that it is preserved and retained,” Messer muses. He points out the scrawled notes, the columns of figures, the mule’s names on the interior walls. “We’re saving all of this.”

The work, which requires about six months, demands Messer’s stewardship as project manager.

Hunnicutt says with obvious delight, “The first thing people ask me, is, can the community come in? I tell them, absolutely, you can now!”

That mule barn is soon to open, housing the café and community meeting facility at the campus center. A selfless core group have brought a quirky landmark a new purpose.

Messer, a determined preservationist, had kept that possibility alive from the very beginning.

A Preservationist with an “Unromantic Task”: Stop Bulldozing History

“Scott’s work is the kind of unromantic task that is absolutely essential for making informed decisions for buildings and landscapes that hold meaning for generations of people,” says Melissa Tufts, director of the Owens Library and Circle Gallery at UGA.

“In our young country, we have felt free to bulldoze, build, and reconfigure in the name of progress, but these efforts have a price that goes beyond financial considerations. Many of UGA’s facilities hold stories and have served a multitude of purposes, which makes them all the more valuable. Here at the College of Environment and Design we try to instill an understanding and appreciation of cultural landscapes—places that evolve, yes, but also maintain ties to the people who used and learned from them. Our campuses are living testaments to Georgia’s public educational

history and we appreciate Scott’s dedication and expertise.”