The Anatomy of a Leader

How Mayor Allen Joines Skates to the Puck

By: Cynthia Adams | Photos By: Nancy Evelyn

On a Friday afternoon in summer, Mayor Allen Joines worked in his courthouse office in downtown Winston-Salem, N.C. The usually quiet town was busy, preparing for an influx of national figures to arrive. It was gearing up to be a long day, preceding an even longer weekend. Joines, who received an MPA from Georgia in 1971, was readying for the memorial of a personal friend, whose given name was Marguerite Annie Johnson. But most Americans knew the very famous poet best by her nom de plume, Maya Angelou.

Angelou’s death had cast a long pall over the quiet Southern town where she lived and worked. And it cast Joines, Winston-Salem’s longest-serving mayor, into the public eye as the one who announced her death to the public.

Joines had appeared in newscasts and front pages during the past week, discussing the death of a friend who was not a political figure, but a woman of letters who became an ally. The next day, he was in the national spotlight, sharing a stage with President Bill Clinton, First Lady Michelle Obama, Oprah Winfrey and other headliners. The entire city of Winston-Salem was suddenly at the center of the news, and it was, like the mayor, ready for its close up.

Joines’ gray pinstripe suit was crisply tailored and polished. A brilliant blue tie was efficiently knotted, his shoes shined, and overall appearance impeccably photo-ready.

He was both attentive and in a mood to talk despite coming events, or perhaps, because of them. Angelou’s memorial was to be broadcast nationally the next morning and the city was already clogged with media and arriving notables. But despite the seriousness of the approaching task, Joines smiled about his affection for the University of Georgia. He keeps an irreverently titled book about Georgia Dawgs (Damn Good Dogs!) on his desk, one that he had to cover when school children recently visited him at City Hall.

Mayor Allen Joines, Winston-Salem, NC-Photos taken in lobby hall

At age 67, Joines is athletically trim and youthful, despite clipped gray hair. And Joines’ public admires him, crediting him with revitalizing a town that languished as tobacco and banking, staples of their economy, died away.

“Our downtown area was totally underdeveloped, so far as restaurants, arts, and innovation goes,” says Barbette Dunn, who works as an administrator in the hospitality industry. She has lived in Winston-Salem since 1993.

With a population of 236,440, Winston-Salem was built on tobacco (R.J. Reynolds began here in 1875) and banking (Wachovia bank was also started here in 1911). The air was once heavy with the smell of tobacco, wafting from downtown plants rolling out popular Salem and Winston brand cigarettes. It is also a town that gave birth to Piedmont Airlines (now US Airways), and Texas Pete hot sauce. Main Street was home to the first Krispy Kreme donut shop in the nation. In recent years, Winston-Salem has reinvented itself, with a focus upon biotechnologies and medicine. Today, Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center is the largest employer.

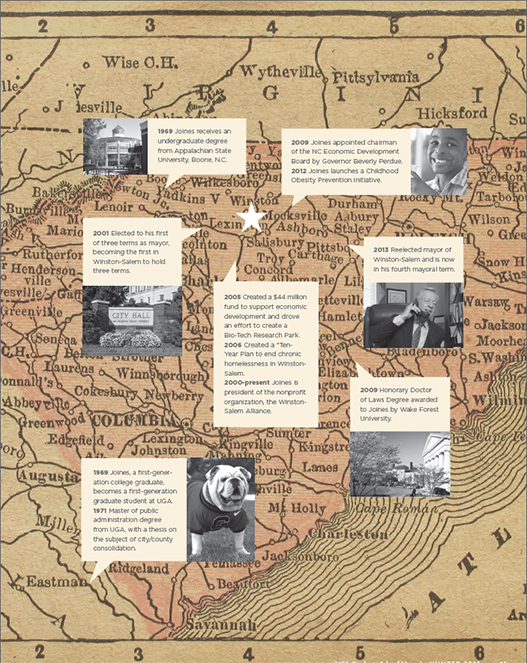

Joines led an effort to revitalize the downtown’s core. He also created a $44 million fund to support economic development. He also drove an effort to create a Bio-Tech Research Park, intended to result in 30,000 new jobs in 20 years. There were other recruitment initiatives, entrepreneurial projects, and undertakings intended to re-direct the city’s identity.

According to a 2014 study by UNC-Charlotte’s Urban Institute, Winston-Salem is now projected to hit a population of 561,000 by 2030, significantly eclipsing its larger neighbor,

Greensboro.

“He has put together a fabulous vision. That’s why nobody runs against him, because he is so awesome,” Dunn says. He has given the city a life it didn’t have. I’ve never lived in a city where the mayor cared more about the people than any agenda. You’ll hear that everywhere you go.”

Joines has never had a silver spoon existence, and might have become a farmer. A child of rural farmers and builders in North Wilkesboro, N.C., Joines chose differently when he envisioned his future. He became an Eagle Scout, and once visited a training camp for Scouts in New Jersey. It was an eye-opener for a young boy from the Appalachian foothills. “I had this curiosity about life,” he explains. And a credo of honor was already deeply imprinted.

But Joines was more studious than thrill seeking. He remembers telling his mother he might like to become a history teacher. She replied that she would support him in his decision. “And when I cease being mayor,” he muses even now, “I would love to teach.”

He attended undergraduate school at Appalachian State University in nearby Boone, N.C. Then, a professor suggested graduate school. The professor was ASU’s Frank Rich. Joines entered the MPA program at UGA in 1969.

At first, Joines was intimidated by Georgia’s enormous campus. “UGA was overwhelming,” he says. “I attended Appalachian State University undergrad, and ‘App’ had an enrollment of 9,000.” As a married student, he lived in an Athens trailer park while his wife taught in Barrow County.

“There was a restaurant in Athens that served barbecue goat every Friday,” Joines says, his gray eyes nearly crinkling shut as he laughs. “I tried it. I grew up in a meat and potatoes setting, and had a very energetic palate.”

When Joines stepped into the much larger environs at Athens, he discovered new mentors. He rattles off names, beginning with Robert T. Golembiewski, then the department chairman of public administration. “He taught me organismic theory. I visited him, and he always had a symphony playing, maybe Wagner.”

UGA “did a good job of establishing a strong basis,” he says. Joines already knew he wanted to work in government following graduate studies.

Joines quickly plugged into the Institute of Government at Georgia. “Vince Marino—he was working on a book and allowed me to write a chapter. He was such a mentor, and taught his great writing skills.” He also drew upon lectures in real life scenarios. “I remember a class on collective bargaining, and learned a lot about issues there,” he says.

Joines recalls the research and writing for his thesis on the subject of city/county consolidation, which was instructive for him in years to come.

He credits UGA for underpinning his career, providing him “a strong foundation.” The theory learned at Georgia, he says, helped him in “avoiding the traps” when he eventually negotiated a sanitation worker’s strike as an administrator.

Joines completed his master of public administration degree in 1971.

After graduation, he was hired by former city manager John Gold in Winston-Salem, who put him to work on the city’s budget. Joines served in various positions from 1971-2000, including assistant city manager. Gold’s influence as a mentor was also important to him.

On November 6, 2001, Joines was elected mayor. He has since served three terms, and has become an almost unbeatable candidate, with strong grassroots appeal. After 14 years as a civic leader, Joines is mentioned in political circles as a possible senatorial or gubernatorial candidate. He admittedly considered higher office in 2006. But for the record, he says there is still work he wants to do in Winston-Salem.

Plus, there is his work as the president of the nonprofit organization, the Winston-Salem Alliance. The nonprofit’s office is directly across the street from City Hall in the Wells Fargo building, and he divides his time between those two. The alliance was created in 2002 to, among other things, stimulate economic development and improve the vitality of corporate leadership, Joines explains. “There is an advantage to the city that I do both,” he says. “So much of the work dovetails. But I have to be absolutely transparent.” He was also appointed chairman of the NC Economic Development Board by Governor Beverly Perdue in 2009.

Transparency has emerged as a theme in Joines’ civic life. It may explain his political resilience and appeal, and why Angelou’s eventual counsel made such good sense to him.

“LAY EVERYTHING ON THE TABLE…”

In public comments to the local press, Joines said about Angelou: “Our city is mourning. It’s mourning the loss of that strong voice that spoke of social justice, spoke of equality, spoke of domestic violence…. But the good news is that voice lives on in her poems, in her plays, and in her books and in her songs.”

Privately, Joines discusses how he met Angelou in the 1970s, when the City hired her to work with a summertime cultural program.

A life in government led Joines down unexpected pathways, such as that of finding advice from a writer and poet who happened to work for nearby Wake Forest University, or WFU. (Like Angelou, Joines was awarded an honorary doctorate by WFU. He received his honorary degree from WFU in 2009.)

The mayor and the poet came to know one another early on in his career. Angelou advised him during a tense period in Winston-Salem’s history when resident Darryl Hunt, falsely convicted of rape and murder, was freed due to incontrovertible DNA evidence. Hunt had already served nearly 20 years. The mishandling of the case ignited deep resentments.

“It was early in my mayoral career, in 2003,” Joines recalls. A group of local ministers confronted the mayor, telling him the city was about to explode with tensions. He spoke with Angelou, seeking her opinion. She advised Joines, “Lay everything on the table.” He took her word, and did so, sparing the city race riots. He says thoughtfully, “Maya personified when passion and giftedness meet. I saw that in Maya,” Joines says. Their trust, and resulting friendship, lasted her lifetime.

Joines is now in his fourth mayoral term. When he was reelected in 2013, he was resoundingly endorsed by every city paper.

“He is the genuine person you see,” Dunn says about Joines. “I’ve never heard a bad word about him.”

Joines chose a different path, becoming not only a first-generation college graduate, but continuing to UGA for graduate studies.

A VISION OF SOMETHING FINER

On a Monday evening last September, Joines entered the Council Chambers at the historic City Hall on Main Street. He wore a crisp white shirt, red tie and gray suit. Thirty-seven people had gathered for the meeting and there was a full agenda ahead. As mayor, he called for a moment of silence.

Joines says he asks for guidance during those moments.

“He’s been a good mayor. Good for Winston-Salem,” says Diane Hampton, who was in the gallery. Hampton is a civil engineer working for the N.C. Department of Transportation. She was on hand due to a consent agenda item, concerning proposed reconstruction and changes to exits on Interstate 40, which dissects the city.

Joines was purposeful and efficient, dispatching the business of government. Within 20 minutes, eight agenda items had been resolved. After allocated time for public comments, the mayor and council went into closed session.

Later that week, Joines celebrated his birthday. He had a full day planned, which began with a morning work out before hitting his two offices. But there was not a birthday cake, nor even a cupcake, in sight when he arrived at City Hall. He launched a Childhood Obesity Prevention Initiative in 2012, and wants children and parents to understand the importance of good nutrition and education.

An assistant in the mayor’s office, Jennifer Haydon, says the boss walks the walk. Haydon said her boss avoids sweets so he probably wouldn’t have any. “Maybe fruit, or a muffin,” says Haydon.

But if he did relent and have a treat, Joines later admitted it would have to be banana pudding. Or peanut butter, which he says is a weakness, and eats by the spoon.

But there seem to be few weak moments in the life of Allen Joines, as even his hobbies are purposeful. Woodworking and painting are outlets he enjoys, as well as playing bass in a band. He has just finished making wooden planters, and also an art project that will be auctioned off for charity. He keeps pictures of his finished work on his smart phone.

He is focused and disciplined, working out three days a week with a trainer and watching his weight. “My daughter says I’m anal,” he jokes. She also teases him about his mania for organization. “I alphabetize the spices in the kitchen cabinet,” he admits and laughs hard. But focus and hard work only gets you so far; Joines says that perhaps vision is more important.

“I’m looking at what it would take to be in the top 50 cities,” he says. He doggedly works at his plans and intentions. In 2006, Joines created a “Ten-Year Plan” to end chronic homelessness in Winston-Salem. Eight years later, chronic homelessness is reduced by 58 percent. He is also an advocate for green and sustainable building. His speeches to that end are “inspiring” says Emily Scofield, who heads the US Green Building Council’s North Carolina Chapter in Charlotte.

“Mayor Joines has been a member of the USGBC’s advisory council for the last two years. He offered us valuable advice,” she says. “’Don’t overthink certain things. Take action.’” She says he was an early signer of the Mayor’s Climate Protection Plan and is working to create workable sustainability in Winston Salem. “Through his leadership, Winston-Salem has been very forward thinking.” For a city of its size, she finds they are well-respected.

Only a few blocks away from City Hall, citizen Dunn paused from her downtown work to proudly discuss Winston-Salem’s traction. She says she appreciates that the town is revitalized, but is deeply proud of the fact that Winston-Salem is invested in art and innovation.

It begs the question, where does this energy and vision for this city’s momentum come from? What is the source?

Sitting by a window in the mayor’s office, Joines considers the question. “By being aware of the environment. The trends.” And then he tells an anecdote about a hockey player (one whom Joines physically resembles) named Wayne Gretsky.

“Somebody asked Wayne Gretsky about his success,” Joines says, and then paraphrases. “He said, ‘I skate to where the puck is going to be.’” Joines is trying to do this, skating to the puck rather than looking back to where it once was.

That evening, Joines will celebrate his birthday with several friends. He will cook the celebratory meal himself, which he has already planned.

But for now, his eye is on the moment, and he turns practical. He may give himself the gift of a reasonable workday.

“I’ll have to get away from work in time to do the grocery shopping,” Joines says, largely to himself.

His assistant, Haydon, gives a little smile, and nods knowingly. No doubt, Joines will be looking forward to the next year, and the next birthday, and the next big goal. Towards something finer.

“OUR CITY IS MOURNING,” ALLEN JOINES SAID ON JUNE 5TH LAST SUMMER WHEN HIS FRIEND, MAYA ANGELOU, DIED. “IT’S MOURNING THE LOSS OF THAT STRONG VOICE THAT SPOKE OF SOCIAL JUSTICE, SPOKE OF EQUALITY, SPOKE OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE PREVENTION, SPOKE OF THE IMPACT OF BLACK THEATER.”