Survivor: The magical determination, near invincibility and indomitable will of Joey Tripp

By: Cynthia Adams | Photos By: Nancy Evelyn

Joey Tripp has met Wynonna Judd and Jeff Foxworthy, most of the Atlanta Falcons and Atlanta Braves, but none of them made the impact of an ordinary volunteer at the Egleston pediatric hospital in Atlanta. The kindly volunteer kept a young patient (and future UGA scholar) named Joey Tripp company while playing video games.

Tripp, who completed UGA’s graduate program in nonprofit management from the University of Georgia’s Institute of Nonprofit Organizations, has worked through childhood conditions that might have daunted a lesser spirit. Tripp overcame formidable odds, becoming the first in his family to obtain a graduate degree. This is the remarkable story of Tripp’s internal navigational system, which never failed him, while facing the incredible set of obstacles to reach his goals.

When Joey Tripp attended the UGA Graduate School’s Emerging Leader’s Program in Dillard, Ga., what some of his colleagues noticed was his uncanny resemblance to actor Daniel Radcliffe, who portrayed Harry Potter. “I also share the same birthday with Daniel Radcliffe (July 23rd)”.

Like the fictional Potter, Tripp has a calm demeanor and twinkling magnetism. Also like Potter, he dealt with loss and overcame it to become an accomplished UGA graduate student chosen in 2013 for the prestigious Emerging Leaders program and a UGA “Amazing Student”.

Unlike Potter, Tripp lacked the benefit of a wand or magic cloak, but nonetheless achieved feats that most would almost describe as pure magic.

On the first day of Emerging Leaders, Joey Tripp stood among the 25 chosen for the program in a large meeting room. Each of the graduate students was asked to write key attributes, listing self-descriptions on a large piece of poster paper underneath their photograph. This was part of the icebreaking exercises preceding a weekend of leadership training the students were to undergo.

Tripp, a genial man with a youthful face, bright green eyes, and quick smile, considered before jotting down a laundry list of interests and characteristics. At the bottom of a list of attributes, he scrawled with a red marker, “childhood cancer survivor.” In a room filled with exceptional students with amazing experiences, his statement stood apart. Tellingly, Tripp had written the comment last, like an afterthought.

At the age of 10, Tripp received a terminal diagnosis for stage four osteosarcoma, or bone cancer. He was given six months to live. The cancer had grown at such a rate his medical advisors believed he had other tumors elsewhere in his body. It had spread from his femur to his lungs (twice), then his spine.

Tripp quickly underwent the first of 30 surgeries he has undergone in the past 20 years. He relapsed with cancer four times during a seven-year fight. However, in no way did cancer define him, nor does it now. By the time you read this story, Tripp will be 30 years old.

The year Joey Tripp’s life changed was 1995.

It was a Sunday morning when Tripp complained of sudden, specific and severe leg pain. His mother, who had decided to enter college as an adult, thought her son had a bad case of growing pains. She gave him a Tylenol before the family headed to church. Tripp tried to make it through the Sunday service, and began to weep as the pain grew unbearable. The family left church and drove one hour to the local emergency room in Macon, Ga., north of the farming community of Yonker.

Tripp’s parents were relieved to find a neighbor working in the hospital’s radiology department that afternoon. The X-ray revealed a problem so severe that the nurse’s demeanor changed completely. The ER physician warned Tripp to put no weight on his left leg, and he was eventually referred to Dr. Monson, an Atlanta surgeon. About three months later, Tripp was in Atlanta awaiting surgery for a femur transplant.

“Dr. Monson said, ‘My first priority is to save your life and my second is to save your leg.’ He told me, ‘Joey you have cancer.’ I didn’t know what that meant. They did a tissue biopsy; I still didn’t understand what cancer meant until I went to my first appointment with the oncologist. It was there the reality of the situation was setting in.” Tripp and his family had entered a foreign world, frightening and hard to fathom. He recalls his mother looking as if she had been crying and his dad “looked like he had hit a deer.”

A very frightened young boy who had heretofore been healthy recalls seeing the other children going through chemotherapy.

“All of them looked alien. Pale, no hair—bald, with sunken faces.”

What followed was life changing. “I’ve had 30 surgeries,” he says, qualifying surgeries versus regular procedures or treatments. “I consider a surgery when you are given sedation. My left femur had to be transplanted; I had to have a spinal fusion—that was a 21-hour operation. I’ve had surgery on my right femur and they removed the growth plate.” He has had additional surgery on his tibia for limb lengthening, necessary because of scoliosis forming in his lower back.

The Tripp family then had to navigate a netherworld of capped insurance, then financial challenges when his father’s union job at an Atlanta aluminum can manufacturing plant was eliminated. His mother left her college studies.

“The first year I had cancer, I started giving up hope. I became really depressed and resorted to anger a lot. I wanted to be normal and for people to stop pitying me. I felt like my life was being controlled by everybody else.” His treatment meant Tripp was periodically rushed to Atlanta for blood transfusions. He found friendship primarily with hospital volunteers who sat with him and read or played games.

He had one refuge, which he fiercely protected. “The only thing I had control over was my bedroom. So, if I noticed something had been moved, I went berserk and even kicked a hole in my bedroom wall. I saw what I was doing to my parents. I became existential; my parents seemed hopeless. And then, I realized what I was doing was not helping anyone.”

For a young boy with great curiosity, he was now separated from his old life and friendships in Yonker. Tripp couldn’t attend the fifth grade, and there was no home schooling program in the summer. “A teacher dropped work by twice weekly,” he recalls, but he had little interaction with other kids.

“I was the first kid in my county to have a publicized battle with cancer,” which meant other children feared the illness, thinking they could catch it like a common cold. “Unbeknownst to us, someone contacted the Macon Telegraph about my diagnosis and my dad’s job loss. A front page feature article was written featuring my family.”

Now Tripp was not only dealing with illness, but with greater isolation. “I’m the first kid in my community to have cancer, and (other) children did not want to hang out with me because they didn’t want to catch cancer.” He was alone, apart from his family.

Then, like his look-alike Harry Potter, Tripp began practicing some personal magic involving his focused green eyes and his generous mouth.

He smiled.

Joey Tripp and parents Marie and Joseph in Yonker, GA. Photographed in front of old store on family property (belonging to cousin).

“I started to, even though hurting emotionally, I started to fake a smile.” Tripp discovered brandishing a smile was the only way his parents looked happier, too. It was a way to cloak the pain, and somehow made him feel better. A smile, Tripp discovered, was a sort of magic he could wield.

Despite the optimism and the smiles, Tripp faced a series of teeth-gritting challenges as he moved into high school. With frustrating regularity cancer reappeared. “I only went four days of my ninth grade before relapsing; so for me, technically, my 12th grade was like my freshman year.” He spent approximately one year in actual classroom time.

“I graduated with my class from high school, although I was only in a whole year of high school during my senior year.” When Tripp graduated from Dodge County High School, despite his rare classroom time, he “ranked 17th out of 192 students. I was also a Senior Superlative!”

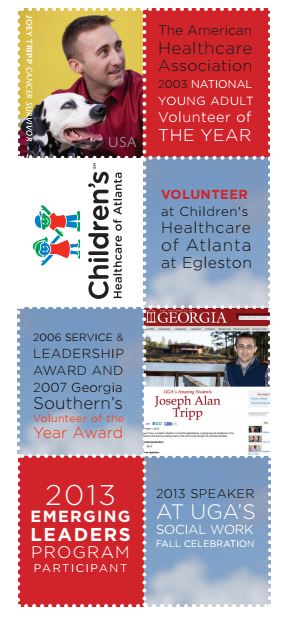

It was now not only possible, but realistic to envision a higher education. He set goals to earn an associate degree. In 2003, Tripp received the National Young Adult Volunteer of the Year from the American Healthcare Association during their conference in San Diego, California.

Tripp attended Middle Georgia State College and earned his associate degree while still acclimating to extracurricular and college life. He received the college’s 2006 Service and Leadership Award.

He then began working towards a biology degree at Georgia Southern University. In the fall of 2007 Tripp signed up for 16 hours of upper-level biology and biochemistry. “It took six years to graduate with a B.S. degree because I took so many different classes that did not fall under my area of study.” He also received Georgia Southern’s Volunteer of the Year Award, having netted more than 1,309 hours of volunteer time. He was frantically catching up with life.

“I was editor of the GSC Core paper; I hadn’t had the luxury of doing any of that stuff. And, I took photography.”

He had already decided to attend medical school and had spent one summer shadowing three of his favorite physicians.

Medical school, and becoming a physician, had become part of his self-definition. But repeated bouts of chemotherapies had taken a toll on Tripp’s long-term health, adversely affecting his medical school admission scores. “Then,” Tripp says, “it was not my definition.”

In what had become his signature move, Tripp re-evaluated.

He swallowed the brutal reality that there was an alternate purpose for his life. He looked to the horizon. Tripp volunteered with a dizzying number of community groups, read self-help books, and re-imagined his future. Then, he decided to use his experience with nonprofits for a different vocation.

Tripp started looking at graduate programs, but worried about testing well, faced with chronic medical concerns. He took the GRE admissions test three times. “I was disheartened and ended up having another surgery. But I went ahead and applied to graduate schools.”

Tripp set his heart on getting into UGA—he would be the first in his family to attend Georgia. His admission was deferred.

Then they found another tumor in his abdomen in the fall of 2012. The surgery left him with what he calls “a C-section scar, but the tumor was benign.”

He waited. In December 2012, Tripp got a call on his cell phone from UGA. “I was in a store to buy safety gear for directing traffic for our family Christmas lights display.” He had been accepted into the graduate program—with only two weeks to move from Yonker and register.

He didn’t care—he felt pure joy shoot through him. “I started jumping up and down right in the store, I was so happy.”

The signature Joey Tripp smile he flashed everyone in the Warner Robins hardware store was effortless and real.

In Athens, Tripp flung himself into extracurricular activities, making up for an isolated youth. He worked with the Jackson county Habitat for Humanity, the Piedmont Rape Crisis Center, Pulaski Tomorrow, Athens Area Humane Society, Athens Farmers Market, Helping Hands Community Outreach, Camp Sunshine, and Camp Twin Lakes.

And nobody was more amazed than Tripp that he had done so much so fast, after all the hiccups.

When Tripp scribbled with a felt tip pen on poster paper in the fall of 2013, he had summarized himself in a few terse phrases for his fellow students at Emerging Leaders. He was only two months from earning his graduate degree. He had maintained a 3.96 GPA at what is arguably one of the finest graduate schools in the nation. In the run up to his graduation, he was selected as a speaker at UGA’s Social Work Fall Celebration and as a UGA Amazing Student, featured on the University website.

Since graduating, Tripp began actively interviewing for his dream job to become an executive director of a nonprofit organization. He also set about ticking things off a long to-do list, hiking to the top of Yosemite Falls. (“I had to take a lot of Tylenol,” he says with a wince.) He got a passport, and plans to visit Europe. He set more goals.

In his youth, a compassionate volunteer had unimagined impact. So, when Tripp has an open afternoon, he says he will find someone needing a friend, and listen. “I’ve experienced the power and impact that has on a person,” he once wrote, “and I hope to have the same impact as the volunteer who visited me.”

Tripp describes how a fellow cancer patient (one newly rediagnosed) reached out to him to ask, “How did you handle relapses?”

He suggested she have a goal to focus on while in treatment. “I asked what was she passionate about. She takes great photography, so I suggested she start showing the world through her eyes.”

“Living is not just waking up and getting out of bed; living is getting up and having purpose.”

He navigates the emotional terrain of vulnerability and loss like a rehearsed and graceful artist; Tripp says you must find the means to talk about it, and then to visualize something beyond pain or loss.

And Tripp, with correction to slightly askew glasses, flashes his brilliant green eyes and focuses upon his own new horizon, which almost always lurks behind one believed lost.

About Emerging Leaders

Since its founding by former Dean Grasso in 2004, outstanding graduate students such as Joey Tripp have been selected for intensive professional development training through the Emerging Leaders Program, or EL. This experience is fully sponsored and funded by the Graduate School.

Many EL alumni are now notable leaders in their own fields. Presenters like Praveen Kolar and Fenwick Broyard are past EL participants who returned as trainers. Other UGA alum, such as Centers for Disease Control executive, Sarah Smith, not only return as presenters but view EL as a prime recruiting ground.

For more information on The Graduate School’s Emerging Leaders, go to: http://www.grad.uga.edu.index.php/current-students/professional-development/emerging-leaders-program/