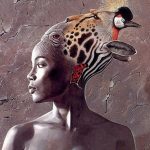

Stephanie Toliver

Wonder Woman

By: Cynthia Adams | Photos By: Nancy Evelyn

Even finding speculative fiction writers from diverse backgrounds is a challenge says doctoral student Stephanie Toliver. She knows; she has become such a writer herself and also has worked to assemble a resource of diverse writers.

Can the success of the blockbuster hit, Black Panther, help change that dynamic? Perhaps it can, in having a diverse audience “seeing themselves in narratives that aren’t tied to violence, death, and pain due to the color of their skin.”

Within a specialized literary field, Toliver focuses upon “representations of and responses to people of color in speculative fiction texts to discuss the implications of erasing youth of color from futuristic and imaginative contexts.”

Stephanie Toliver pursues Language and Literacy Education at the University of Georgia. Not surprisingly, given that in her childhood, reading transported Toliver to a world that defied limitations, showcasing heroes and heroines who had transformative experiences.

In the thrilling world of her imagination, Toliver had no limits whatsoever.

Her research emphasizes reading education, literature, and language arts. Make that, speculative fiction.

“Speculative fiction covers sci-fi and fantasy, as well as the hybrids, like superhot, magical surrealism, and blends of subgenres,” explains Toliver.

Often referenced as the “what if?” genre, it includes fiction which breaks with traditional laws at work in our known world.

Outwardly, Toliver is polished, giving the appearance of the experienced professional educator she is. On a sunny summer morning, she wears a cheerful print dress and a perpetual, brilliant smile.

But think of Toliver as a modern super heroine type, like Marvel’s Misty Knight, or Storm from “X-Men”: one possessing super powers, hiding in plain sight. Well, not literally, but within her richly imaginative world, Toliver employs a love of science fiction and anime and shows her students a world of possibilities.

In the classroom, she uses young adult and science fiction genres to help promote social justice and equity Toliver was preparing to present an educational workshop in Las Vegas titled, “Diverse Fantastic Characters and Where to Find Them.” Yes, she laughs, it is deliberate wordplay based on J.K. Rowling’s similarly titled work.

Once upon a time, she was a disenchanted teen who had one, singular and burning passion: to read, especially science fiction. Beyond that, Toliver only knew she hated school and found it utterly boring.

“I didn’t have texts that showed girls like me, and I didn’t have teachers who challenged me.”

As a young girl living in Omaha, Neb., she once chose a Wonder Woman costume for a children’s party. “I wore it,” she says.

“There were no Storm costumes,” Toliver adds.

At the party, Toliver was told by another child she “couldn’t be Wonder Woman because you’re Black.” The comments stunned and stung.

In recent years, Toliver taught in Tallahassee, Fla., before accepting a job in the Greater Atlanta area teaching English and reading to high schoolers. The irony is not lost upon her.

“I went from (being) the kid who announced to my mother at 17 that college was out. I didn’t see school as a challenging space or a representative space; I didn’t think that college would be any different.”

Toliver gives a laugh and a shake of her head. When a teenager living in New Castle, Pa., Toliver was once on the verge of being held back a grade, despite a strong average and passing scores. It was all due to lack of attendance; there was no other reason.

It was not for lack of ability; Toliver often skipped school, which lacked challenge and creativity. She was, however, riveted by “Animorphs”, “Star Trek”, and “Dragon Ball Z”, televised programs which “defined my childhood.”

She watched Wesley Snipes in Blade and Chris Tucker in The Fifth Element.

However, the speculative fictional works and movies that inspired programs and films were dominated by white male writers. L’Engle herself had decried that fantasy and science fiction was a closed shop, open to white males only. Black-authored science fiction is often rejected by publishers and occasionally even by readers.

But Toliver had also discovered the groundbreaking works of Octavia Butler. Butler became the first African American science fiction writer to receive a MacArthur Fellowship. Her writings were sometimes deeply unsettling; she foresaw a dystopian future, which was Orwellian and prescient.

As a writer, Butler had netted honors once reserved exclusively for white males. By professional measure, she had no limits.

She was a woman of color, but she was writing about super powers and heroines who were also diverse.

Butler herself had super powers, Toliver thought.

Meanwhile, a series of happy accidents transformed Toliver’s future and illuminated her path. In what turned out to be a fortunate shift, Toliver’s mother’s insurance job moved the family from Pennsylvania to Sanford, a town in central Florida. Here, Toliver “got a new slate,” she explains.

It wasn’t that Toliver found her new school in Sanford more challenging. If anything, she was even “less challenged,” she admits. “I didn’t have to do much of anything…it was repetitive work.” In her senior year, a guidance counselor asked Toliver, “where are you going to college?” and Toliver replied that she wasn’t going.

Yet things were soon to change. Toliver’s mother had other ideas for her daughter’s future. She took her to visit Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University, a historically Black college, and Toliver had a change of mind. She decided she was going to college in March of her senior year. Toliver quickly took college entrance exams for the first time. Her scores were high, and qualified her for scholarships fully covering her tuition.

Toliver already had a 4.0, an average she had maintained since the 11th grade.

Meanwhile, Toliver’s mother had plans of her own, and earned a bachelors degree after hours while working

full time.

Toliver’s research interests include speculative fiction, narrative analysis, Afrofuturism, and Black girl literacies. Like female fantasy writer Madeline L’Engle, she was drawn to the study of English early in her life. But more like Octavia Butler, she is challenging further obstacles faced by minority writers.

Toliver did well in her studies, but was unhappy with her public relations major. She was asked to teach

in the same place where she student taught. She took the job full-time, remaining four years.

Both Toliver and her mother decided to continue their studies.

Toliver entered graduate studies at Florida State University, while teaching and four months pregnant. She studied “curriculum and instruction with an emphasis in English education.”

Toliver continued working, eventually leaving Tallahassee and accepting a teaching job outside Atlanta, nearer to family members.

Soon, she decided to enter doctoral studies, choosing UGA. “It was the only school I applied to,” Toliver smiles.

She interviewed and was accepted into the Language and Literacy Education doctoral program. “I teach teachers now…and I have people who say they haven’t had a Black teacher until college.”

Toliver’s now in her fifth year of doctoral work From her first class, she began to understand she could use both her love of sci-fi and love of anime with young adult literature. “I honed it in a little more.”

In 2019 Toliver was awarded the NAED Spencer fellowship, which encourages research relevant to the improvement of education. Only 35 fellowships were awarded nationwide and will support her work for four years. “Over 400 people applied for this award nationwide,” she says.

By their own description, the Spencer Fellowships “support individuals whose dissertations show potential for bringing fresh and constructive perspectives to the history, theory, analysis, or practice of formal or informal education anywhere in the world.”

NAED SPENCER FELLOWSHIP

The Spencer Foundation’s Dissertation Fellowship program provides training opportunities for education scholars and education journalists to develop new foundational knowledge and to participate in research that can support better policy-making, practice, and deeper engagement with the broader public. The Dissertation Fellowship program is committed to supporting the research training of promising doctoral students from a wide range of disciplines, taking up research relevant to the improvement of education. Funded by Spencer, but administered through the National Academy of Education, the $27,500 fellowships support individuals whose dissertations show potential for bringing fresh and productive perspectives to the history, theory, analysis, or practice of formal or informal education anywhere in the world.

https://www.spencer.org/grant_types/ dissertation-fellowship

Toliver had distinct ideas about how to bring a fresh perspective to the classroom, and specifically to the teaching of speculative fiction.

During the first years of her research, Toliver says she was sometimes asked a surprising question: “Do Black women read sci-fi?”

She answers, “It was known as a white male dominated genre…because that’s what they know. But there has been sci fi written by Black people since the 1800s.” She cites Black authors such as Octavia Butler, Charles W. Chesnutt and W. E. B. Du Bois.

Toliver also had teachers pose another issue. They challenged the lack of books with diverse characters. She felt she could become a resource.

“I realize a lot of teachers say, ‘where do we find these books?’” Toliver had insights and began to cobble together resources. “Some are self-published. I created a list of 150 books with Black and Asian characters, Latinx, and Native-Americans, and LGBT, and disabled characters.”

OCTAVIA BUTLER

Octavia E. Butler was the first science fiction writer to receive a prestigious MacArthur Foundation “Genius” Grant and the first African-American woman to garner widespread acclaim writing in that genre.

“She was a pioneer, a master storyteller who brought her voice—the voice of a woman of color—to science fiction,” said Natalie Russell, assistant curator of literary manuscripts at The Huntington in San Marino, Ca. “Tire d of stories featuring white, male heroes, she developed an alternative narrative from a very personal point of view.”

A 1954 sci-fi film, Devil Girl from Mars, inspired Butler to take on science fiction. Russell said, “She was convinced she could write a better story than the one unfolding on the screen.” discoverlosangeles.com

- Octavia Butler (Photo: OCTAVIA BUTLER, FACEBOOK)

- Anyanwu, a character from Butler’s book Wild Seed

“I teach teachers now…and I have people who say they haven’t had a black teacher until college.” -Stephanie Toliver

The University of Wisconsin in Madison compiles research about diverse characters and writers in the Children’s Cooperative Book Center. There is a low percentage of books with minority figures or authors, says Toliver, “but there is an uptick.”

The interest in and demand for more representative literary figures were real. Toliver has also quantified that interest.

“I did a survey on Black women’s reading of science fiction,” she says. She posted the survey on Facebook and Twitter, “asking if you identified as black and femme. I had 365 responses in three weeks to the 30-question survey!”

Toliver also wanted to know the respondents definition of science fiction. Her analysis expanded the conversation and reach.

“People have been speaking out. In 2014, #WeNeedDiverseBooks began, creating a collective term about representation in youth literature. Diverse books were already there, but the hashtag helped the conversation grow,” she says.

Then a fantasy film called Black Panther made history in 2018 and proved both a need and hunger for diverse works in print and on the big screen. Toliver discusses the 2018 superhero film produced by Marvel Studios and distributed by Walt Disney Studios

The Academy Award-winning Black Panther did something that helped Toliver’s and others’ work. It shattered long-standing preconceptions about diversity not having a market. The film not only broke several box office records, but also became 2018’s highest-grossing film in the United States and Canada. Worldwide, Black Panther became the second highest grossing film for 2018.

More significantly, here was a film, “about black people seeming themselves in a narrative that wasn’t tied to violence, death and pain due to their skin color.” Toliver says the viewers saw characters unencumbered by their color.

ACADEMY AWARD-WINNING BLACK PANTHER

Black Panther is the 18th movie in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, a franchise that has made $13.5 billion at the global box office over the past 10 years. (Marvel is owned by Disney.) It may be the first mega budget movie—not just about superheroes, but about anyone—to have an African-American director and a predominantly Black cast. Hollywood has never produced a blockbuster this splendidly black. time.com/black-panther

Imagination precedes reality.

Toliver describes “seeing yourself in imaginative places, when we dream of something different,” citing writer Walidah Imarisha. “We are speculating in fiction.”

In recent times, she also revisits Butler, her old childhood favorite. She not only stands the test of time, but now the writings are important to Toliver’s research. “I re-read her Parable series a couple of years ago, and it was so prophetic that it was scary. I’m using those novels now in my dissertation because of how amazing they are.”

The seminal works Butler produced decades earlier have enjoyed a resurgence of interest given she employed what she called “grim” themes of a radicalized America. Her stories and novels portrayed a frightening, fragmented, racist society that rejected science and embraced intolerance and violence. As a New Yorker essay described, some readers sought Butler’s writings out as a sort of survival guide in a dystopian time.

Fantasy writer Madeline L’Engle, another female writer among Toliver’s childhood favorites, has also proven timeless. L’Engle famously blended time and time travel in her famous work, A Wrinkle in Time.

“I feel we can talk about what happens in the past… or the present. This is what is happening in the world, what might it look like,” Toliver says, with a cup of coffee in hand.

“Whenever we dream of something different, we are engaging in the fantastic, in fiction,” she says. We must imagine a different future.

Her own child will soon be six. “I want him to know there are people who look and think differently from him.” Toliver is teaching him about a diverse reality, without “jading him, or making him cynical about the world.” She reads widely with her son.

She wants to cultivate positive relations, not fear. “I think about the world being created for him, and the world I want him to have. I try to have conversations with him about race, identity, and know there is a world with different people.”

“Whenever we dream of something different, we are engaging in the fantastic, in fiction. We must imagine a different future. ”

— Stephanie Toliver