Sarah Anderson

Over the Moon

By: Cynthia Adams | Photos By: Nancy Evelyn

A six-months long exhibition spearheaded by a UGA graduate student trains a lens upon Georgia Senators Richard B. Russell Jr. and Herman E. Talmadge and their roles with moon exploration 50 years ago during the heyday of the space race. On display was wide-ranging space memorabilia, including satellite images and pop cultural items documenting the lunar landing. Thanks to this well-conceived exhibition, visitors could place the epochal event in the context of Georgia history.

Moon Rocks!, the exhibition at the Richard B. Russell Building Special Collections Library, officially marked the July 20, 1969 anniversary of the lunar landing of the Apollo 11.

It also provides historic background framing the event.

UGA’s Special Collections houses eye-opening mementos of that chapter in U.S. history. Russell, who Chaired the Senate Armed Services Committee, was called the “most powerful and influential man in Washington, D.C.” by U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk.

His powerful committee roles meant he had great control over the federal budget. Russell was also on the Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Science until his death in 1971, hence his powerful and long connection to NASA.

Talmadge, who served as Georgia governor before becoming a four-term senator, had a less known role but his presence on the Georgia stage of events was notable.

In truth, Talmadge was once a strong proponent, yet he later called for ending the exploratory moon expeditions that began in the 1970s.

In 2019, Sarah Anderson, a graduate student in the museum studies certificate program, helped offer a unique perspective on the moon landing, particularly as marked by Russell’s extraordinary relationship to those key to the moon race.

Russell was a UGA alumnus who served as a Georgia Governor before entering the Senate.

Talmadge, who also served as governor, earned his law degree at UGA.

“While Talmadge wasn’t very influential in a national sense, he was someone to whom the public turned in order to express their opinions, and someone they relied on to make a change,” says Anderson.

As she notes, “Reflecting the sentiments of his constituents, Talmadge believed that the exploratory missions were superfluous after the initial goal of landing men on the moon was achieved.”

Anderson, who worked at the Air and Space Museum for two years after earning a history degree at UGA, brings her own behind the scenes experiences to bear. She has had the rare privilege of working with, even touching, some of the rare, even extraordinary items that pertain to the history-making 1969 event. Few were privy to things that Anderson worked with in the Smithsonian archives.

At UGA, she had access to a surprising range of pertinent artifacts donated by two elected figures who had a unique, lesser known role in the space race.

This exhibition was Anderson’s baby. An avid and experienced historian, she curated it herself following time working at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

Along the way, she gained a new nickname: Moon Girl. As over 400 people queued up to view the Moon Rocks on exhibition at UGA’s Richard B. Russell’s Special Collections during the opening day on July 16—where moon rocks would be displayed for a short window— Anderson watched the line of people eager to see Georgia’s own stash of moon rocks and couldn’t help but think about the public who never even accepted the reality of Apollo 11’s accomplishment.

The Moon Rocks! exhibition celebrated an iconic national event 50 years ago and remained at the Richard B. Russell Building Special Collections Library through December of 2019.

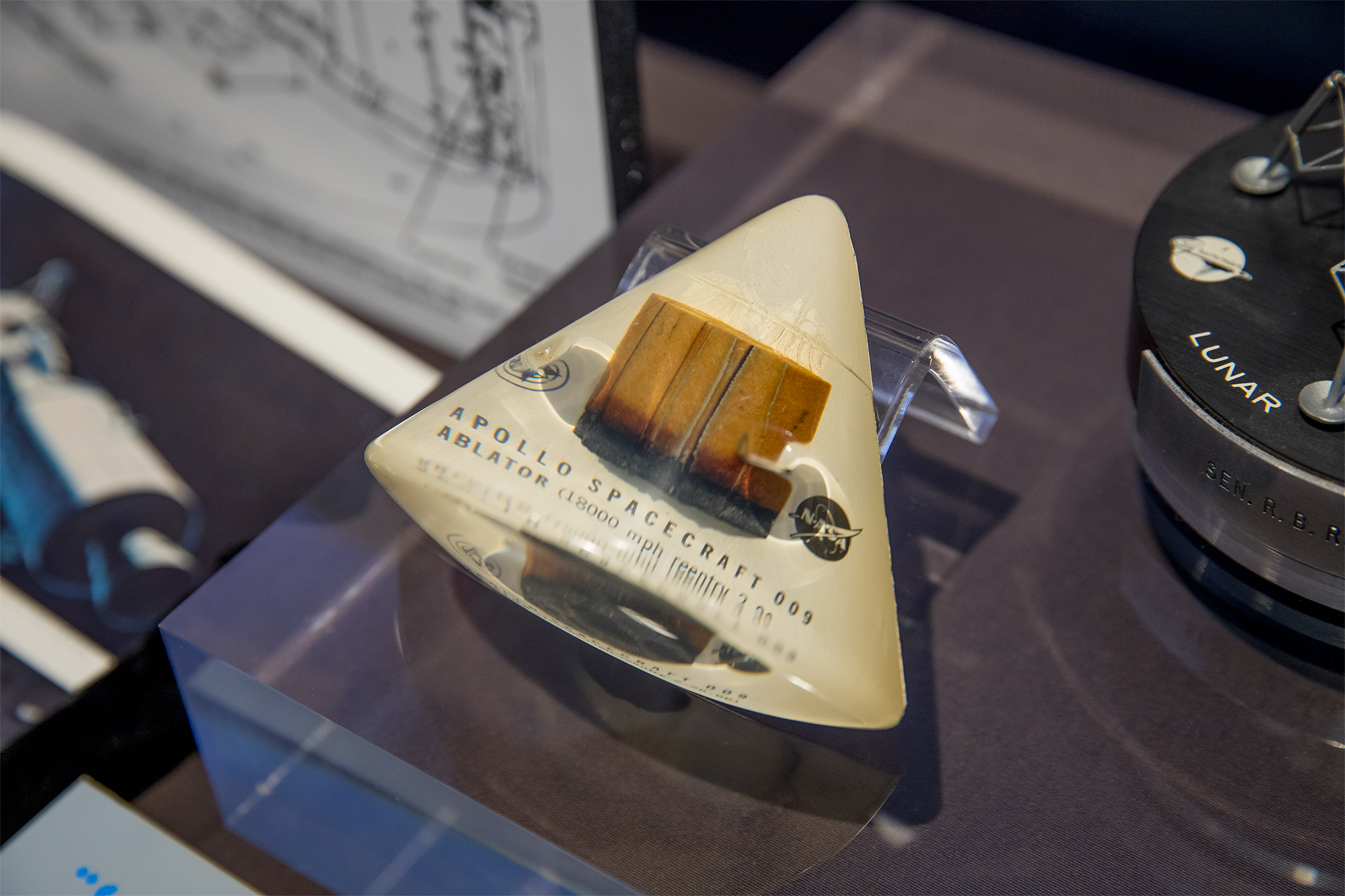

Anderson says the exhibit attracted more than 430 people, double the usual traffic, on opening day. She was stationed with the exhibit the entire day, explaining the artifacts. The moon rocks were returned to their permanent home in the Georgia Capitol Collection immediately after a brief showing. The remaining objects are owned by UGA. The Life magazine was owned by Richard B. Russell. The Apollo 9 spacecraft ablator (bottom) is a piece of the protective material that encases the command module protecting it from the extreme heat that occurs during reentry. Most of the ablative material is burned up in the process of reentry. The coin in the case at the top is a replica of the silicon “Goodwill Message Disc” presented to Senator Russell in 1969. In a NASA release dated July 13, 1969, it was said to carry statements by Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon, and 73 world leaders. It listed Congressional leaders, and the four committees of the House and Senate responsible for NASA. NASA’s former and then administrators were also named.

The naysayers had a name: such people were known as moon mission deniers. The deniers appeared to be outnumbered, if the enthusiasm for this one exhibit was any indicator.

“We kind of understand why some people think that the landing is not real…that we didn’t really go to the moon,” she noted that week.

Moon Girl was more bemused than anything. Historic events are viewed through many lenses. And denial is also one of those lenses.

Anderson has read all the conspiracy theories: the stories about the seemingly permanent footprints, the flag that never unfurled and looked stage-propish.

Each of those are easily dealt with. “The (lunar) photos are really interesting. Footprints don’t leave the moon, so they’re always there. And the flag has a special mechanism to hold it up because there’s no wind. Stuff like that. So, it looks interesting.”

A totally hostile-looking environment, she observes about the moon.

“Supposedly it all looks the same,” Anderson jokes. “There are different kinds of rocks—that’s about all the geology I know.” She laughs.

Months later, Anderson is still thinking about Apollo 11’s brief sojourn to the moon’s surface. The moon rocks owned by the state of Georgia were briefly on exhibition at Special Collections—literal rock stars themselves.

Moon Girl enjoys a little joke when pressed to describe the now-absent Georgia moon rocks. “Moon pebbles?” she suggests, and giggles.

But there is a more serious, intense tie underlying Anderson’s love of history, and why those denying

historically documented events is personal. One thing can keep her up at nights: if events of history are not fully grasped, we cannot learn their lessons.

Ironically, there are even those today who insist that the Holocaust never happened, despite the mountains of evidence documenting atrocities and eyewitness accounts. This, she laments, is at great cost to present day civilization.

Take Anderson’s own grandfather, John Anderson, who flew 24 missions with the 388th Bomb Squadron before being shot down over Germany and captured. For eight months, he was a POW in three camps, starving as were so many, and left by the roadside as the Nazis fled during the Liberation.

His captors didn’t believe he would live. “He was scooped up and saved,” Anderson says. “He recovered in a hospital in France.”

John Anderson’s experiences were documented in John Nichols work, The Last Escape.

He was uppermost in his granddaughter’s mind when she found herself in the Smithsonian archives, with access to World War II archives, relics and aircraft. His reality was at her fingertips.

“I started working there because my grandfather was in World War II,” says Anderson. “He was in a B-17 during World War II. And, I was interested in aircraft. Working (at the Smithsonian) with space artifacts was just an added bonus for me.”

She pauses. “But now, it gained a whole new meaning—learning about the inter-generational aspect.”

Her grandfather’s story had a happy outcome and led directly to Georgia.

He returned stateside after liberation, later joining the music faculty at UGA. “He continued his education after the war while working for the University.”

Anderson discusses how her grandfather went on to become assistant UGA bandleader, and even met his future wife, Hazel, while she was a student. Having once endured forced marches while a POW, he now marched joyfully before crowds of cheering fans and his growing young family. His granddaughter smiles at the irony.

The Andersons became a family of devoted Georgia Bulldogs.

During Anderson’s turn at the Air and Space Museum, she did collections-based works. Her work was truly hands-on—the care of rare items requires this.

She discussed a day’s conservation work at the Smithsonian where she got to touch some of the Apollo mission artifacts.

Anderson says “I dusted the containment module the men were in for 21 days after the Apollo 11 module.” Recently, Smithsonian conservators discovered previously unnoticed astronaut graffiti inside the Columbia command module. Access to that artifact is very limited, she says.

Simply being within touching proximity to the iconic module felt goosebump special for an ardent student of history.

Anderson’s work with the moon may have ended, but she still gets intriguing questions from visitors (like, were seeds taken up in the space module?)

As the 50-year Apollo 11 mission anniversary loomed, there was discussion of an exhibition. Both the state of Georgia and important UGA alums had a special connection to the event—and unique artifacts in their care.”

“It was an impetus to change,” she says. “The Space Race was a massive innovation, for technology, computers, satellites…internet.”

Anderson was excited the moment those discussions began in earnest. A fun and arresting name for the idea surfaced: Moon Rocks!

“Jill Severn, the Head of the Access and Outreach Unit came up with the idea and the name for the Moon Rocks! Exhibit,” explains Anderson. The public was excitedly watching televised documentaries of events half a century earlier, and the audience ratings were high.

The synergy of the race was real and still riveting. To have planted a flag on the surface of the moon and bring back a cache of rocks and geological materials captivated the public’s attention.

Few had ever seen actual moon-related artifacts, let alone moon rocks.

“The Russell Library tries to focus on nationwide events which allow our unit to draw attention to the diverse nature of our collections. Knowing that Richard B. Russell had served on the Space and Aeronautics subcommittee, Jill felt that it was important for our library to produce an exhibit focusing on the 50th anniversary of the moon landing.”

It wasn’t merely a good idea. It was a great idea, and Anderson was energized. Perhaps it would become her first curated exhibition.

The idea was green-lighted.

“Since I had experience with space artifacts through the National Air and Space Museum and I had shown interest in learning how to fully develop an exhibit, Jill and Kaylynn Washnock (my supervisor), provided me the opportunity to proceed in researching and then curating the full exhibit…as well as being the lead in organizing the exhibit opening event.”

With an exhibition approved, Anderson was officially off and running. She had touched and experienced important space artifacts. She had a family connection to flight via her grandfather.

And, she was becoming the special sauce for a cannot-lose concept: Moon Girl.

As Anderson discusses, over 400,000 people ultimately worked on the mission and space race. A huge endeavor, which she mentions was stunning and ambitious in scope.

UGA held an early contract with NASA, Anderson points out, related to information technologies. The NASA connection resurfaced this summer when a journalist working on an article found it while sifting through a mass of space-related information.

Anderson had found a reference to a contract in the 1969 Business Management Magazine, which is displayed with the exhibit.

“It was in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution,” Anderson says. “The article was on the IBM Supercomputer, and they mentioned us in 1965.”

Photo: HISTORY.NASA.GOV/AP11

On July 20, 1969, American astronauts Neil Armstrong (1930-2012) and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin (1930-) became the first humans ever to land on the moon. (Michael Collins was the command module pilot.). About six- and-a-half hours later, Armstrong became the first person to walk on the moon. As he took his first step, Armstrong famously said, “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” The Apollo 11 mission occurred eight years after President John F. Kennedy (1917-1963) announced a national goal of landing a man on the moon by the end of the 1960s. Apollo 17, the final manned moon mission, took place in 1972.

Apollo 11 carried the first geologic samples from the Moon back to Earth. In all, astronauts collected 22 kilograms of material, including 50 rocks, samples of the fine-grained lunar “soil,” and two core tubes that included material from up to 13 centimeters below the Moon’s surface. These samples contain no water and provide no evidence for living organisms at any time in the Moon’s history.

https://www.history.com/topics/space- exploration/moon-landing-1969

https://www.lpi.usra.edu/lunar/missions/ apollo/apollo_11/samples/

The machine, which resided in the Lumpkin House, was a $3 million dollar investment, spurred by a UGA agricultural professor with a fascination with statistics. Supercomputing typically refers to parallel processors, all working as one. In the 1960s, UGA’s supercomputer was a mainframe, explains Don Adams, an engineer who worked for IBM in Johannesburg, South Africa. Earlier computing machines began as large tabulators that morphed into more sophisticated machines.

NASA farmed out work to various units in order to process huge amounts of data, he speculated. (As a matter of fact, NASA brought their own staff from Huntsville, Ala., renting the UGA computer. The investment paid for itself swiftly. See Chickens, Computers And Space.)

Adams adds that the IBM 7090 series mainframe was designed for large scale applications, doing arithmetic and scientific, technical calculations as opposed to business calculations. “Parallel processes are all about speed and bandwidth,” he explains.

“By having multiple processors, each taking a small portion of the task, or a fraction of the process, it thereby speeds up the actual processing of the original task—by dividing it up across these processors, then assembling the results back into a composite at the end.”

Perhaps one such task was calculating the spin of the Earth and its gravitational field, which NASA would use to help speed the rocket to the moon, the engineer offers by way of illustration.

Researchers, mathematicians, and computer professionals played a role in support of landing men on the moon and safely returning them to Earth. And, given the relative rarity of supercomputers, and UGA having geographic proximity to Huntsville, Ala., the calculation to purchase such an expensive machine was a solid idea.

The investment paid handsomely for UGA. NASA and others rented the supercomputer and it was quickly paid for—making it a great investment, unique resource, and earned UGA a place of relevance in an epochal scientific endeavor.

From political cartoons, memoranda and news clippings about supercomputing, Anderson did the same—establishing relevance to Georgia. She digested such pieces of information with eagerness, assembling a larger portrait of the efforts in support of the mission, the public discourse, and then, its aftermath.

She provided something invaluable: context.

For a younger generation under 50 years of age, that context was second-hand.

“I didn’t see the moon landing but my parents did,” Anderson says. “It’s nice to have that experience. Something they can share. People like to reminisce. It’s important to give them something they can latch onto and share.

“It inspired people. It gave them a perspective.” There was the westward-expansion appetite that left America in need of a new horizon. She mentions how Americans strive for advancement and power—and the moon offered both.

“Property is power,” Anderson adds.

As the astronauts toiled on the moon surface, gathering samples, an American flag was planted, and more.

A goodwill disc with various greetings from Earth left on the moon remained; a replica given to Russell was in the exhibition and on display.

Then there is America’s near obsession with the astronauts themselves, which Anderson finds both fascinating and also curious. Despite her scrutiny of the men who went to space, she is not quite able to understand the public obsession fully. She laughs and jokes, “But, I’m not a white man.”

She wonders aloud what Neil Armstrong, the commander, would say about his experience with the press in the aftermath.

Was it overwhelming? What about his having to undertake a 40-day goodwill tour immediately following the training, mission, isolation in the trailersized module Anderson actually has experienced, before the crew’s eventual release?

It was trailer-sized, but must have seemed large compared to the confinement of the space module, she says. That graffiti later discovered inside? It was simple. One of the astronauts counting off the days before their release.

“What is true?” Anderson asks, suggesting the pressure to perform publicly. “Show puppet?”

She also helps humanize the larger dynamic by offering personal facts, such as how little the astronauts actually netted financially.

Despite the risks, there was no appreciable financial gain. The crew were prevented from capitalizing upon their inestimable fame.

Astronauts earned about $14,000 a year in the late sixties, she points out.

“Aldrin was worried he wouldn’t come back; he didn’t have insurance for his family. So, he signed all these autographs before he left and gave them to his wife (as a form of financial insurance).”

MOON ROCK BANDITS

Thanks to Russell’s long political reach, Georgia has its own space rocks. Actually, all the states do.Georgia’s reside permanently in Atlanta. They were whisked away from the UGA exhibition after a very short stay on July 16 and returned to their permanent home as part of the Georgia Capitol Collection.

Occasionally, some of the moon relics held in collections worldwide go missing. NASA has its own Special Forces who go in search of missing moon rocks.

Anderson mentions the case of Honduras space rocks which disappeared. The rocks were sold during an uprising, having been placed on the black market. Therefore, she explains, “millions and millions of dollars went missing.” Luckily, “A NASA Special Forces man recovered them,” she adds.

Sex on the Moon, the 2011 book with a cult following, concerns another moon rock theft (and eventual recovery) event.

Photo: ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY, TOM STORY

After Apollo 11, the simple fact is, “We became the super power.”

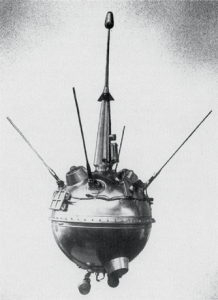

Anderson again provides context. “Russia saw that, too. The mentality was, if we could get to the moon, we could bomb anybody on Earth.” She points out the Soviets crash landed an unmanned spacecraft on the moon on July 29, 1969, just as the Apollo 11 crew were making history.

The world order was affected but impetus to return to the moon had waned. Georgia’s Talmadge cooled to further exploration, and did not throw support behind future missions.

“China, Israel have gone to the moon. But there were not many manned missions past 1972 when we stopped the Apollo mission. We only had six manned missions on the moon.”

As Anderson sifted through artifacts, she examined each piece with the insight of looking backwards after decades. She studied everything possible: pop culture, commentary, simultaneous events, and the motivations of the space race’s proponents and detractors.

“We were working with the most important pieces we had in storage. This exhibit gave me an understanding of why people are so in love with space.

It was an enormous task. Anderson analyzed political cartoons, photos, and even “boring legislation,”

she says with a wry smile.

Then there were the space race souvenirs: state flags and moon rocks, which were given to each state afterward by President Nixon.

“A lot of flags supposedly went to the moon, and items like this stamp, or this medal,” she says, walking through the exhibition display cases.

“We have coins that went to space, and photos. A Georgia state flag went on a space mission—to the moon. But I don’t know, what did this actually mean? Was it on the landing module or did it just orbit around the moon?”

There were 135 country flags as well, she says. “I need to find the flight logs to know what exactly was on board.”

Anderson is working to establish if an artifact actually went to the moon and clarify what it really signifies.

“Several items were gifted to both the State of Georgia and Senator Russell by NASA or individual organizations that were said to have flown to the moon or ‘landed on the moon.’ However, I am still working on finding the exact locations of these artifacts during the mission—whether that means they were on the Lunar Module or held in the Command Module. Did they land on the moon or just orbit the moon?” she emails later. What is the item’s precise provenance?

In curating the exhibition, Anderson hoped to vet the list, or manifest, as to what actually went into the Apollo 11 module. Thus far, no luck.

She especially wonders what was among the astronauts’ private possessions allowed on board.

For sheer fun, they placed a ballot box inside the exhibit, which allowed visitors to vote on two burning

questions.

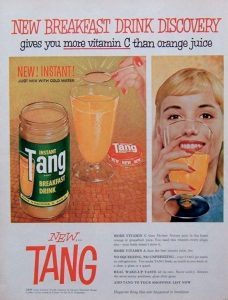

Did they think we should return to the moon, and, would they drink Tang if they were an astronaut in space?

She was completely certain that Tang was consumed in space. “We found the meal log…that’s how we know Tang was drunk in space,” says Anderson. “It was a part of the astronaut diet labeled as ‘orange drink.’”

Does Tang actually exist anymore?

“Yes, it does. But it’s really bad for you,” says Anderson, again smiling. “We had it at the opening event. And we ran out so fast.”

She adds, “NASA got upset with Tang because of the mass commercialization. The flag that went onto the moon was bought from Sears and NASA said they couldn’t advertise it.”

“LAUNCH YOUR DAY WITH THE GOODNESS OF TANG”

Tang was used by early NASA manned space flights. In 1962, when Mercury astronaut John Glenn conducted eating experiments in orbit, Tang was selected for the menu; it was also used during some Gemini flights, and has also been carried aboard numerous space shuttle missions.

Tang first appeared on the market as an orange-flavoured breakfast drink in 1957. In 1959, its more recognizable powdered form arrived on shelves. It was mostly sugar—9 grams in each 8 ounce serving—but it was also packed with vitamin C, vitamin A, calcium, and vitamin E.

Sales were poor until 1962 when John Glenn drank Tang in orbit. His Friendship 7 flight was the first time an astronaut would be in space long enough to need food and drink. Millions watching the mission saw Glenn eat applesauce and drink Tang out of a bag. It was a space age treat moms could bring home for their children from the supermarket. Sales skyrocketed.

Turns out Tang is popular according to their interactive balloting. And so is the moon landing, at least today, with the perspective of time. But in the context of 1969, landing on the moon was highly charged with accusations of being exorbitantly costly, a wrong-headed use of resources, and potentially an embarrassment.

What if we failed?

What if the Russians beat us to the Moon?

(Although denied at the time, Russia was engaged in the so-called Space Race, a fact revealed accidentally during Glasnost.)

The pendulum of public opinion swings back and forth concerning space exploration, says Anderson. “It’s very strange. There was such paranoia about Russia. When we landed on the moon, Russia was also trying to do the same.”

Despite his misgivings about the Space Race, Talmadge played a part that became a place keeper within the history of Apollo 11. He was instrumental in bringing the lunar (namesake) Stone Mountain Rock to Stone Mountain Georgia.

As a public programming fellow at the library, attuned to the groundswell of interest in the 50th anniversary, Anderson notes, “He felt that it was important both to bring attention to the amazing human effort behind the moon exploration, the fact that (astronaut) John Young graduated from Georgia Tech, and to bring more attention to the recently completed sculpture on the mountain.”

Talmadge’s inclusion in the retrospective at UGA was valuable and instructive, Anderson says.

THE SOVIET UNION AND THE MOON

The Soviet Lunar program had 20 successful missions to the moon, including the first flyby and image of the lunar farside. Ale xei Leonov, a Soviet cosmonaut who in 1965 be came the first person to walk in space, was scheduled to walk on the moon be fore the Soviet Union abandoned its efforts for a manned lunar landing.

- The Luna 2 Soviet spacecraft (Photo: NSSDC.GSFC.NASA.GOV)

- The first image of the far side of the Moon, taken by the Luna 3 spacecraft in October, 1959.(Photo: NSSDC.GSFC.NASA.GOV)

Although Anderson is normally a solid sleeper, she worries during restless nights about knowledge without context. She was a teaching assistant when the instructor placed an image of Reagan’s campaign posters on the board. The instructor asked who originated the slogan.

Every student identified Donald Trump.

Every student was wrong.

“There were audible gasps as the students acknowledged Reagan’s campaign slogan, ‘Let’s Make America Great Again.’” Anderson sighs.

“Students don’t have a sense of history. The focus is upon STEM. Students learn facts that aren’t relatable.” She says it is historians’ work to provide a perspective, provide a voice, and lend context to knowledge.

“Take classes outside history to interpret places with conflicting story lines.” Anderson is a social scientist, as much as she is an historian. Her grandparents used to relate her family history, more than once discussing her grandfather’s POW experience in World War II.

Anderson wants to make America relate, to remember again.

“Even if we are great, we are flawed,” she adds. The American people “generally want to view the world as simpler than it is.” People in the past “had to exist in real time.”

Much of this thought didn’t originate with Moon Girl’s work on Moon Rocks! She parses out threads, following the warp and woof of history.

“Journalists live for the origin of the story. Many historians say there is almost never an origin.” She adds later, “history is ever evolving and always causal of the events that preceded.”