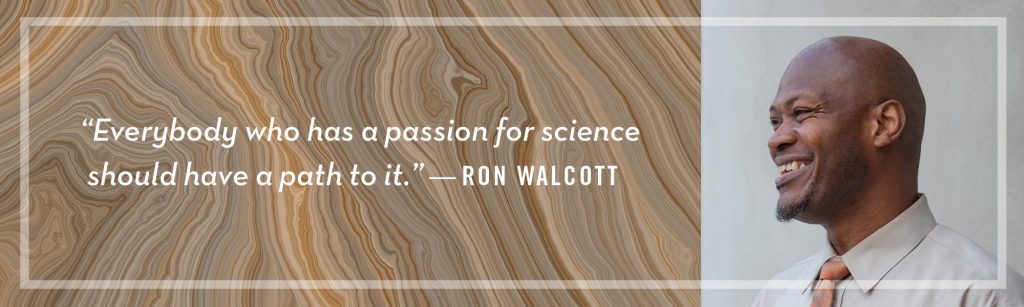

Ron Walcott: The Hibiscus and the Bee

By: Cynthia Adams | Photos By: Nancy Evelyn

Ron Walcott became associate dean of the Graduate School this summer. He is also a faculty member in the Department of Plant Pathology, where he has taught for nearly 20 years.

During his tenure at UGA, Walcott developed an international reputation in the bacterial pathogenesis of plant hosts. During that time, he has secured nearly five million dollars of research grant support. “In addition to his research prowess, Dr. Walcott has a strong commitment to training the next generation of scholars, having secured eight grants from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to enhance training of women and underrepresented minorities in his discipline,” says Graduate School Dean Suzanne Barbour. “He also brings extensive experience as an administrator at UGA, as Assistant Director for the Center for Teaching and Learning’s Lilly Teaching Fellows Program (2007-2011), as Graduate Coordinator for the Department of Plant Pathology (2015-present), and as the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences Assistant Dean and Director of the Office of Diversity Relations (2008-2013).”

In announcing his appointment, Barbour notes “Dr. Walcott’s commitment to academic excellence has been recognized through his selection as a UGA Senior Teaching Fellow and as a member of the UGA Teaching Academy.” She also noted his achievements in mentoring and training graduate students “and securing extramural dollars for their support.”

Ron Walcott, a scientist, has a philosopher’s bent for self-examination. On the other hand, he takes great pleasure in the outdoors. “There are many sides of me,” Walcott says, then laughs out loud confessing to an inability to be a great gardener.

“I am good at killing plants,” he admits, with a wide grin.

There are few personal effects in Walcott’s office at the Graduate School, where he is the new associate dean, apart from a borrowed purple African violet. He cannot repress another grin as he admits that someone else tends the violet, so it has escaped harm.

He is going to put something on the walls. It just hasn’t been important, he adds, as he gets to know graduate students, faculty, and staff. He has an immigrant’s view of stuff—explaining he doesn’t like to move possessions or be possessed by them either.

“I don’t like to be obsessed with things,” Walcott says, spreading his hands open, as he describes life with his wife and two daughters (one a UGA student).

He recently had a birthday, and takes pains to express how family time and outdoor experiences are central to his happiness. Things haven’t been a conduit to his sense of fulfillment. Ideas have. Experiences have. One of his prized childhood possessions was a Raleigh bike—a hand-me-down from one of his four older siblings. That and pick-up games of basketball filled many happy hours.

Walcott’s grew up on an idyllic 21-mile long Caribbean island, where he once thought he might become a biology teacher. Perhaps this mindset was incubated by his growing up on an island, a creature of sea, sand, and sun. He was provided a wide horizon. He was far from frenetic urban centers and close to the rhythms and cycles of the natural world on an island only 14 miles wide.

Under the tutelage of a tough teacher, he grew more observant and curious. He tells a story about a hibiscus flower and a bee, a story that illustrates the ah-ha moment when Walcott knew he would become a scientist. “It started with a red hibiscus,” he says. And a great, although strict, science teacher named Mrs. Procope.

“I was in my early teens, looking at flowers,” he describes. “I was in Barbados and we had hibiscus hedges. I would sit and watch them and the bees going into them, going in to pick up the nectar and pollinating. The flowers were so big, you could dissect them and see the ovaries where fertilized ovules would develop into seeds.” The symbiotic interactions of the flower and bee fascinated. Walcott’s scientific curiosity deepened when the biology teacher stressed that he was good at biology and should follow it.

At 6′6″ tall, Walcott was adept on a basketball court and might have focused on sports but for his taskmaster.

“She told me, ‘You are good at biology; you should pursue it. I read your essays and you comprehend it.’” The teacher was tough; she inspired fear, he remembers. Yet her fair-minded toughness commanded respect. “I remember her very well. She instilled confidence in me!”

Problem solving and figuring things out attracted him. In the fullness of time, he started looking at the things within nature that weren’t always so positive. Plant pathology seized Walcott’s academic attention.

A Bright Red Hibiscus…

A well-known example useful to Walcott’s teachings of plant pathology is the 19th century Great Famine of Ireland. The affected who ultimately immigrated to the US came to escape widespread famine and starvation.

“The genetic diversity of the potato was zero. You didn’t have to find seeds, or buy seeds; you just found tubers and put them back in the land.” Walcott shakes his head. Cheap, easy to grow, and abundant, potatoes were a crucial crop throughout the United Kingdom, but particularly in Ireland where poverty was rife. “A lot of people were depending on one commodity.”

When disease came, for as Walcott explains, “Disease will always come” it was 1845. The Irish suffered profound scarcity and hunger. The Irish ultimately waged a battle for independence from the Crown; they had many fewer resources than the UK as the majority of their food and resources were exported to absentee landowners. As the potato crops were decimated, starvation took the lives of more than one million.

Science had not yet advanced sufficiently for the farmers to realize they were perpetrating the very practices that were choking off their food supply. “These things were happening, but the disease had not been acknowledged.”

The point, Walcott stresses, “Is that science has the capacity to help us understand the world around us.” He teaches about how everyone “believed in concepts such as spontaneous generation. They believed if meat was left out to rot, that maggots would appear and was evidence of spontaneous generation!”

The bright red hibiscus that piqued his curiosity caused him “to think about something bigger than someone my age…It goes back to the interconnectedness of things.”

Did the bee grasp what it was doing, he asks hypothetically? No…but there is some process at work, and the question still excites him. Will we ever fully understand the consciousness of living things?

“You have to read to the end of the book before you know how it ends,” Walcott answers enigmatically, and then laughs.

As for books, he read two while a high schooler that had great influence. Walcott’s favorite, Things Fall Apart, is a cautionary tale of devastating culture clash in Africa. “The book made me think about how devastating outside pressures can be. That book resonated with me.” Another, To Kill a Mockingbird, is a classic about ruinous biases.

In some ways, Harper Lee’s novel provided an important map for him. Little could Walcott have dreamed he was destined to leave his island home and one day live in Georgia, only a state away from Lee’s Monroeville Ala. setting for Mockingbird.

Separating Out Biases

Walcott is happy inside a classroom, and keeps an open-door policy. “Students are not blank slates, they come with their own biases and beliefs,” he says, adding he enjoys student interaction and a lively topic. “I ask them to think differently.” One of the differences that education demands is to examine and explore unconscious biases.

He is the youngest of five children and came to Iowa for undergraduate studies. He was 23ish, he recalls. There, he met the very same man who edited his mycology textbook. “Charles Mims,” Walcott says. Mims was a UGA professor and the graduate coordinator in plant pathology.

“When I was young, I would look up to someone and think, ‘I could never be that!’” But as he explains, Mims, who became a long-time friend, was different. Mims was accomplished, approachable and engaging.

“He was from Louisiana and a real down-home, easy to talk to guy. He loved basketball. During the reception he started talking to me, and I thought, ‘OMG, he’s talking to me!’ He made him feel comfortable. That was great. We stayed in contact.”

Soon Mims recruited Walcott to UGA. “He’s still my mentor today, and we go fishing,” Walcott muses. Walcott still likes pick-up basketball; old pleasures have never left him.

His pride in science hasn’t either. He stresses how exacting and tedious research is, how examined a scientific paper is before publication.

“There is certain inherent value in being trained in a thing that you love,” he adds, smiling knowingly. “I’ve invested time and resources getting good at what I do, and everybody who has a passion for science should have a path to it.” Walcott speaks to how scientists maintain neutrality and adhere to strong principles.

This isn’t only what science demands, but what critical thinking demands. “That is what graduate training does; training to separate our personal biases from the task at hand.” This was a lesson learned back in Barbados, observing the hibiscus and then learning to dissect it into its many parts.

The dramatically colored, simple looking hibiscus is a complex plant; things are not always as they appear.

Walcott, curious as ever, is humble. “There is a ton that I don’t know anything about…it scares me and invigorates me,” he admits. Sometimes, too he must hurry to keep a pace that also challenges. He wants to keep a healthy balance; to carve time for a hike in the woods or for another student chat.

Yet, the hands on the old-school watch on his wrist creep towards mid-day. And Walcott has places to go, and students to see, and, as he jokes, plants to kill.