Naoko Uno

On April 3, last year, Naoko Uno won UGA’s sixth 3MT, which is sponsored annually by the Graduate School. Uno is currently researching an infectious disease known as dengue virus. She works with a research team at UGA’s Center for Vaccines and Immunology, in hopes of creating a universal vaccine. She is also an avid musician and vocalist.

By: Cynthia Adams | Photos By: Nancy Evelyn

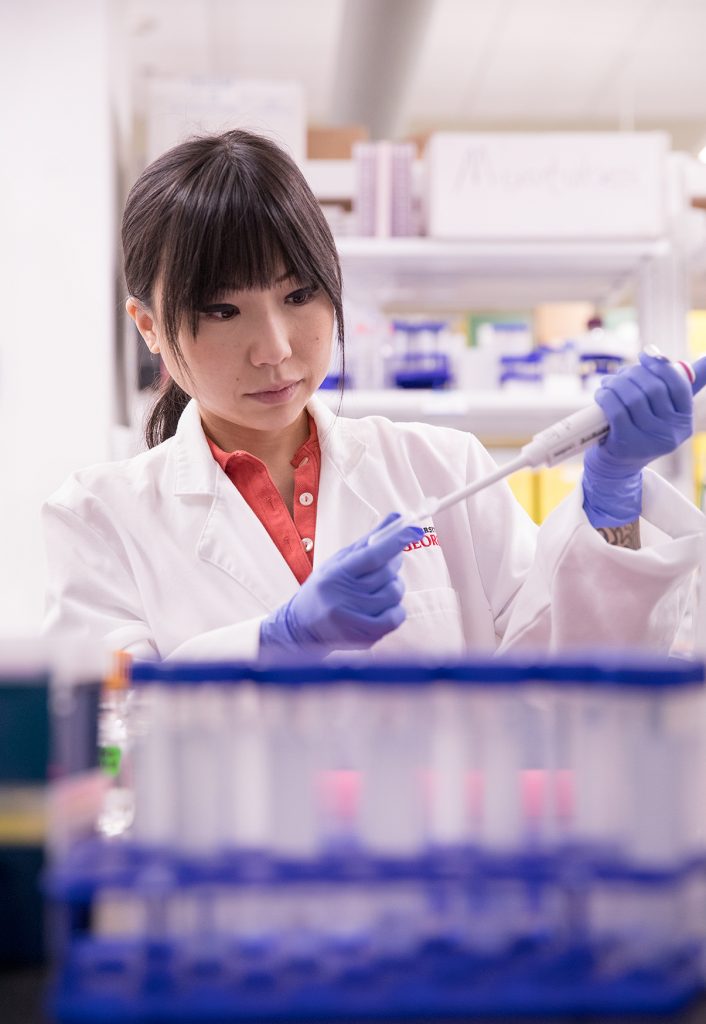

Naoko Uno, the 2018 3MT grand winner and doctoral student at the University of Georgia’s Center for Vaccines and Immunology, lives two lives which intersected neatly and handily last year. On one hand, she works in a laboratory where researchers are developing a dengue vaccine using COBRA, a “computationally optimized broadly reactive antigen.” Their research seeks to create a comprehensive vaccine that will protect against the dengue virus, which has four different strains.

Dengue is also on the rise.

Uno’s winning 3MT presentation was titled, “Designing a Universal Dengue Vaccine.”

But in her off-hours, Uno is passionately, exuberantly making noise rather than running tests. She can often be found pounding the keyboard and singing vocals with several Athens bands, including her very own band, Calico Vision. (Sometimes, she confesses to singing in the lab when working alone at night.)

And so, a stage is a familiar place for the avid musician and scientist, who performs and records music in her home studio.

Yet Uno’s 3MT preparation technique was unconventional, and one inspired by years of mastering piano compositions. It meant learning her three-minute presentation both forwards and backwards.

She tackled her preparations exactly as her music teachers had taught her to master musical pieces. And it worked.

Uno never skipped a beat.

She rehearsed her speech over and again until she could pick it up again seamlessly should she falter, without having to start over. And the effort paid off, netting her first place.

Despite having learned her 3MT speech backwards and forwards, and pushing herself to perfect it, Uno still worried afterward. Distilled to three minutes, the speeches must capture a thesis subject which can be 80,000 words long.

“I didn’t remember if I’d covered all the points,” she says. “Everyone else was so good! I think that got me nervous, because they were so good.”

Yet she won the $1,000 prize, which Uno will apply towards a future family visit to Japan.

“Right now, I’m going to save it…and be a little less poor!”

Researcher By Day

Uno changed her research focus after returning to her native Athens from the West Coast, where she had done graduate studies in nanomaterials and immunology at the Center for Electron Microscopy and Nanofabrication at Portland State University. She also previously worked in vaccine research at the Robert W. Franz Cancer Research Center at Providence Hospital.

Born in Yokohama, Japan, Uno came to Athens, Ga. at age seven with her family. Her father is a scientist, and her mother, a pianist, studied audiology at UGA.

Uno’s grandfather, Saburo Kubota, retired from Toyota and taught Japanese classes at UGA. It was assumed she, too, would remain at UGA, but she sought more independence.

At 18, she left for Portland, Oregon to begin undergraduate studies in physics at Lewis and Clark College. “My father is a physicist,” she explains.

She remained out West, and earned a master’s in applied physics at Portland State, still following in her father’s footsteps. Then, Uno shifted course. It was a daunting decision and required a change in disciplines, leaving physics for immunological research. But there were contributing factors, both academic and personal.

“When I did my master’s, I collaborated with a cancer research institute,” Uno says. The experience there had given rise to a new interest for Uno, which dovetailed with other concerns.

“What drew me to the cancer research was a family tie to cancer; also, even a childhood friend (who had cancer). Because of that, I wanted to start working in cancer vaccines.”

More to the point, Uno felt she “could help a lot more people rather than doing theoretical quantum mechanics.”

Dengue fever

The mosquito-borne viral disease occurs in tropical and subtropical areas. A few facts:

- Spreads by animals or insects;

- Lab tests or imaging often required.

Those who become infected with the virus a second time are at a significantly greater risk of developing severe disease.

Symptoms are high fever, rash, and muscle and joint pain. In severe cases there is serious bleeding and shock, which can be life threatening.

Treatment includes fluids and pain-relievers. Severe cases require hospital care.

She returned to Georgia where her grandparents still reside and entered infectious disease studies at UGA. (Her parents have since returned to Japan.) She joined a dengue virus project around the time that Zika research was growing among university researchers.

“Could my dengue vaccine help or hurt Zika?” she wondered. Zika, like dengue, is also mosquito-borne.

Uno became interested in designing a vaccine for all four serotypes of the dengue virus. Also known as “Breakbone fever,” dengue virus re-emerged in Florida and Texas after a decades-long absence in the U.S.

In 2012, Health and Science stated, “the vicious virus has re-established itself in the South, and mosquitoes are carrying it North.”

Uno adds that dengue “has been theorized to be around for the past 1000 years, previously circulating and evolving in monkey species and spreading to humans.”

The problem is far from new, and difficult to successfully battle back.

Dengue was once rife in the U.S.

“From the 1820s to the 1940s,” wrote Maryn McKenna, “it caused recurring epidemics roughly every 10 years.”

An Austin, Tx. epidemic occurred in 1885 after the dengue virus had already afflicted people in Charleston, S.C. and Savannah, Ga. It felled half the population of Galveston, Tx. in 1897, and struck one in nine Miami residents 37 years later.

Yet, World War II’s mosquito-eradication programs seemed to banish dengue to the tropics. Unfortunately, that didn’t last.

Numbers of cases are still elusive.

“With dengue, it’s hard to keep track of it,” says Uno. “Tropical countries don’t track it. In the 1940s they isolated it, then in the 1980s they upped the surveillance. I think it was always around.”

In the absence of a vaccine, the best most of those at risk of dengue could do to protect themselves was limited to avoiding mosquito bites and taking proactive steps to reduce mosquito breeding areas in water (e.g., in flower pots or garbage cans) around homes.

According to various news reports, mosquito-borne illnesses such as dengue and malaria pose a bigger threat than ever, and are found where they were not reported previously. The need for a safe vaccine is steadily growing.

A Musician and Scientist, At Home on Different Stages

Uno’s 3MT presentation addressed how almost half of the world’s population is at risk of dengue, which is mainly transmitted by the Aedes aegypti mosquito.

There are more than 4,000 species of mosquitoes. But Aedes aegypti is a commonly found pest, known to carry a number of dangerous diseases, dengue being one.

“What should we know and how to respond?”

Uno revisits this question a few weeks later in a meeting near her lab. “It’s hard to figure out viable treatment options; there’s not a treatment. Usually symptoms are mild, but there is a chance you could get severe dengue and die from it, so, it’s important to have the resources.”

It’s frustrating work.

As she notes, “Many cannot get medical care and vaccinations. It’s really hard with Puerto Rico, and hurricane Maria, for example. We have a dengue project with Puerto Rico here at UGA.”

How close is her research group to development of a dengue vaccine?

“During my 3MT talk, I said the current licensed vaccine is harmful in children. That is going to make any new dengue vaccine put through a more stringent checklist. Now, we’re going to have to spend a lot more time making it safe.”

Uno projects that it can “take decades for a vaccine to be licensed.”

There are additional barriers to a vaccine.

“It is really hard because there are four different types. And, there are a lot more complications with dengue. You can get antibodies from, say dengue I, but say you get dengue II. It won’t actually kill it but make it easier for it to go inside your cells. That is what is so dangerous.”

Since her triumph at 3MT, both Uno’s research and musical interests have been affirmed and acknowledged. In June, her band was a winner at the Flagpole Music Awards, which took place at the Morton Theatre. The event is a “kickoff to Athfest” according to the tabloid.

Calico Vision won the Upstart trophy, an award “given to a band that formed during the previous 12 months and made a strong impact off the bat.” In writing about the Upstart win, they reported on the “dream-pop/psych-rock outfit Calico Vision, which made a splash in its first year with a series of memorable live performances involving creative outfits, masks, bubble machines and other ephemera.”

Her mother returned to Georgia in order to see Uno perform during Athfest, an annual music festival. And in August, 3MT judge Shelley Nickle invited Uno to present her work to the Georgia Board of Regents.

It was all music to her ears

Calico Vision band at Caldonia Lounge – Guitar/Vox: Bren Bailey; Guitar: Landon Woodward; Keys/Vox: Naoko Uno; Bass: Nate Lee; Drums: Adriana Thomas

What is the 3MT™ Competition?

The Three Minute Thesis (3MT™) is an exercise that develops academic, presentation and research communication skills and supports the development of students’ capacities to effectively explain their research in language appropriate to an intelligent but non-specialist audience. Master’s and doctoral students have three minutes to present a compelling oration on their thesis or dissertation topic and its significance. 3MT™ is not an exercise in trivializing or “dumbing down” research but forces students to consolidate their ideas and crystallize their research discoveries.

2018 3MT™ Results

Grand Prize: Naoko Uno, Infectious Diseases, Designing a Universal Dengue Vaccine

Runner-up: Kate Zipay, Management, Work Hard, Play Hard: Hobby Jobs, Nostalgia, and Playfulness at Work

People’s Choice: Kristen Lear, ICON Forestry & Natural Resources, A Story of Bat Conservation and…Tequila

Finalists:

Krishna Latha, Infectious Diseases, Breathe Easy: TPL2 Fights Your Flu

Carmen Kraus, Plant Breeding, Genetics, & Genomics, The Shape of Tomatoes

Michael Snell, Psychology, Beyond Identity Politics

Lainie Pomerleau, English, In Their Own Words: The Forgotten Literature of Medieval Queens

Alexis Ramos, Plant Breeding, Genetics, & Genomics, Making Tomatoes Bigger: Mining New Fruit Shape and Size Genes

Alicer K. Andrew, Infectious Diseases, Placental Malaria: A Global Menace to the Miracle of Life

Benjamin Leiva, Agricultural and Applied Economics, Economics and Energy: Getting More Light than Heat