Letitia Rincon Herce

By: Cynthia Adams | Photos By: Nancy Evelyn

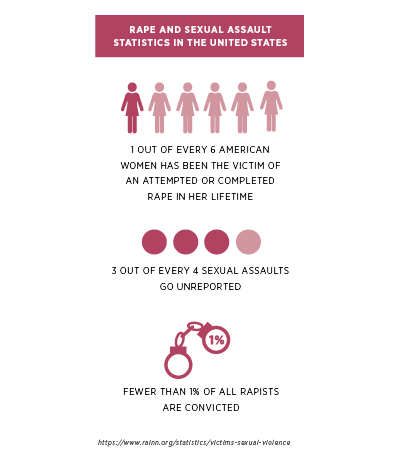

Letitia Rincon Herce is a UGA doctoral student in linguistics, and a recipient of the 2017 Innovative and Interdisciplinary Research Grant for graduate students. · Her research concerns the pragmatics of language in context, specifically concerning how lexical choices affect trial outcomes in rape cases. She offers a staggering statistic, one which underscores the value of Herce’s research: fewer than one percent of all accused rapists are convicted. Much of this is potentially due to how cases are discussed, conveyed, and interpreted.

The 2017 grant she received enabled research undertaken both here and abroad, which allowed Herce to gather important data from rape trials.

Bulls were once much more familiar to Letitia Rincon Herce than bulldogs.

She came of age in Spain, not far from Pamplona where the annual running of the bulls is the stuff of cultural lore. Herce’s native city of Arnedo, Spain is roughly 1.5 hours south of Pamplona, which attracts a million tourists for the San Fermin Festival each July.

Now bulldogs, not bulls, are far more interesting to Herce—and she can indulge and enjoy this fascination. Since coming to the United States for graduate studies five years ago, Herce has discovered a completely different collegiate experience. At UGA, she discovered an even more intensified sense of alumni engagement.

Herce shakes her head wonderingly about the investment and passion that fellow UGA students feel for their alma mater.

“In Spain, I am unsure what the difference is, but there isn’t the same connection with a university.” Although the Spanish are known for their high sense of passion, Herce says she had never before experienced the degree of affection that alumni hold for their alma mater before coming to the University of Georgia.

“I love it,” she says.

In her native Spain, Herce became a first-generation college student with an affinity for languages, undertaking translation and interpreting as an undergraduate. Her undergraduate university’s relationship with Erasmus allowed her to study in Paris in 2011. It was a natural pursuit for a multi-lingual European who could deepen

her mastery of French in the process.

What she discovered was that translation was unsatisfying. “I didn’t love it, translating, but I did like the language part,” she discovered. When she completed her undergraduate degree, she learned about her college’s overseas partnership with the University of West Virginia and Kentucky. “My mother loved the idea of my doing a doctorate,” Herce says. She enrolled at the University of Kentucky and earned a master’s in literature and Hispanic studies, but had decided she didn’t want to work as a translator. What she enjoyed most were the linguistics classes she had taken in the course of her degree work.

Kentucky offered Herce a chance to complete a master’s and doctorate in literature in five years. She earned a masters in literature and Hispanic studies, but she declined to stay in Kentucky for doctoral studies as her interests were now more defined. What she was most interested in was the area of social or pragmatic linguistics.

She applied to UGA.

There Herce met her lead professor, Sarah Blackwell. The meeting cemented her interest in Georgia.

“I visited the school; I loved it! The professors were incredibly welcoming. I had the chance to talk with Dr. Blackwell during the interview and decided not to even finish applications to other schools. UGA was it!”

Herce concentrated her doctoral studies upon pragmatics, the study of language in context.

“Lots of times we say things and are communicating more than what those words mean. In order to understand interaction, you need to study more than syntax (how words are related) or semantics (literal meaning of words) and take into account the intention of the speaker and what he/she’s trying to accomplish with that. Another big part of pragmatics is the study of how the hearer makes sense of what is said and understands what the speaker wants to say, even if it is not present in discourse.”

She also became interested in Blackwell’s research, which led to her own dissertation thesis.

Herce examines the specifics of women witnesses and the judicial process, while also studying institutional context.

“Power relationships are reflected in language,” Herce explains.

If ever there was a time overripe for such work, Herce believes it is now. Although her own research is not related specifically, it is concurrent with the #MeToo movement, which spotlights power struggles between men in power and the women who must cope with a shocking imbalance of power.

The Power of Semantics and the Blunting of Truth

Herce’s doctoral work focuses upon how linguistics may affect trial outcomes, specifically as it applies to rape trials.

As the Washington Post reported this year, the felony conviction rate for accused rapists is less than one percent.

“I’ve always loved police work and crime shows and books and films,” Herce explains. “When I started here at UGA, I thought I was going to do a dissertation in something like forensic linguistics.” She took a criminology course, looking at different types of crime and the professor mentioned the statistics on rape.

“He discussed the amount of rapes in a year.” Herce was deeply affected. She learned that a significant number of people experienced rape and did not report it. Among those reported, there was a disturbing disparity between occurrences of reported rapes and convictions.

The statistics were deeply upsetting to Herce. How has this occurred? Herce believes some of the answers may lie in semantics. There is also an inherent social bias.

“People are predisposed to not believe women,” she says bluntly.

Herce learned rape victims are the only eye witnesses facing a disturbing social bias: there is an inherent belief that they are untruthful.

“If I say I saw a murder, that is one thing,” Herce says. She would be found credible. “But if I said, ‘Oh, someone raped me,’ I think that it is incredibly shocking (that I would likely be disbelieved).”

The bias was overwhelmingly against the victim in cases of rape.

The significance of research in pragmatics in the case of attacks unfolded before her, given the exceedingly low rate of rape conviction. The overwhelming bias appeared to be that juries were sympathetic with the rapist, not the raped.

“I read an article about how men who have been accused of murder and rape are more likely to plead guilty of murder than rape,” Herce adds, as she explains that an exceedingly low rate of conviction means the rapist risks little, or nothing, in denying the charge. A plea deal in a rape trial may not even be sought—statistically, over 99% of accused rapists will not be found guilty or serve time.

How could this happen?

Herce addresses one aspect, which she calls the “cognitive filter” that applies to rape cases.

She asks a singular question, which is: Does the general public even understand how a trial works?

“After a traumatic experience that is rape, there is the second traumatic experience that is a trial…and to fight for those rights to be believed in court.” It is a staggering point; the victim must face off against their accuser in a court of law. And the victim is judged or viewed through a “cognitive filter,” Herce says, one which is “created by the lexical choices of the attorneys.” This discredits the woman’s version of events.

Herce says another point is clear: “The experience of the women hasn’t been taken into account as much as the experience of the men.”

Then there is the fact that many victims will never even report the crime against them, given the heavy, ancient social stigma a rape victim must carry. A general silence on the part of rape victims is prevalent. There is no accusation even made in many instances of rape.

There is no opportunity to even express the crime against them. “Putting your experience in words is what these women don’t get to do…your experience is still disregarded. It’s (viewed as) not important.”

“Cognitive filters” are an aspect of this.

When Research Illuminates Destiny

Herce draws much of her data from rape trial transcripts obtained from the courts, as researchers and observers are typically not allowed to record court proceedings. Creating a verbatim transcript of a trial falls to the court reporter.

“Without permission from the courts I cannot record (a trial in progress) so I am using the transcript for my research. The Open Records Act means everything is available, whereas it isn’t allowed in Spain. Here in the U.S. it is easier to get data.”

Herce will travel to Puerto Rico at the end of the spring semester in order to obtain data there, which has ramifications of its own.

“Because they have a very particular linguistic situation, federal cases are in English, although Puerto Ricans are native Spanish speakers. So, if they don’t have enough competency in English, they have an interpreter.” This means an added layer of linguistic filter—the victim cannot report first person events in her native tongue. In addition, Herce adds that “all of the members of the jury have to be bilingual (in Puerto Rico).” This, too,

affects the available jury pool. That also has repercussions for both the accuser and the accused.

Herce will spend a week reviewing court transcripts in Puerto Rico and potentially observe trial proceedings.

“There aren’t many articles (or at least I haven’t been able to find them) that explore language in rape cases in Spanish-speaking countries or Puerto Rico,” Herce explains.

“What I want to accomplish with this, and what I hope the data provides, is a confirmation of what I (and many people) believe: that linguistic manipulation in rape trials to undermine the credibility of the plaintiff is not just a U.S. phenomenon. It happens everywhere.”

She continues. “By doing a comparative research, I will be able to see if the manipulation techniques used at trial are the same, if they use the same cultural frames, and hopefully, if they affect the outcome of the trial in the same way.”

Herce is making a point of trying to raise public awareness of her research, traveling to conferences and symposia this past semester.

“I am in the Women’s Forum committee in the Romance Languages department and we organize workshops or round tables with the professors for the graduate students and we talk about several problems of women in academia. Between the Women’s Forum and the GSO (Graduate Student Organization), together with the Equal Opportunity Office, we have organized a couple of workshops about what to do if students disclose sensitive information about sexual assault and how should instructors or professors deal with that in a classroom setting. So, even though it’s not my particular research, it’s also a way for us to make people more aware of this in a variety of environments.”

Among Herce’s inner circle are rape victims who did not report the crime.

“One of the big problems with this type of crime is that it’s incredibly under reported,” she says.

“Several reasons can make someone not report the crime; for example, shame. They’re afraid of the consequences or that no one will believe them. They are made to believe that it’s not a legitimate rape. They’ve already had a traumatic experience and they don’t want to be reminded of it and asked very specific details about it over and over again, especially when they know that nothing will happen to the person that did it.”

Ultimately, she hopes her study will “help destigmatize the survivors and make the process less traumatic for them, which will make women and men more willing to report it.”