Karolina Heyduk

By: Cynthia Adams | Photos By: Nancy Evelyn

If UGA researchers are correct, plants native to the Southwest adapted to photosynthesize at the optimal time, allowing them to conserve their need for water. Findings on how these plants have adapted matters greatly in a water-stressed environment.

HOW LONG CAN YOU HOLD YOUR BREATH?

Yuccas, hostas and agave are workhorse plants that nearly every common gardener knows well. But it appears these plants have a valuable secret—a breathtaking one, actually.

Say what?

Magician Harry Houdini was legendary for holding his breath underwater for nearly four minutes. But ordinary plants may hold theirs for much, much longer. If UGA researchers are correct, the plants adapted to essentially photosynthesize at the optimal time, allowing them to conserve their need for water. It’s almost as if they have evolved and hold their breath, according to lead scientist, UGA plant biologist Jim Leebens-Mack.

Why does that matter?

Conserving water is swiftly becoming one of the defining issues of the century. Lester Brown, president of the Earth Policy Institute, describes a water crisis in his book, Full Planet, Empty Plates: The New Geopolitics of Food Scarcity. “The world has quietly transitioned into a situation where water, not land, has emerged as the principal constraint on expanding food supplies.”

Enter Karolina Heyduk, a doctoral student who works on Leebens-Mack’s research team. “I’m interested in how photosynthesis works, and how it will be applied. There are projects right now trying to make plants more water efficient. We’ve known for 40 plus years this photosynthetic pathway helped plants conserve water. But nobody thought to look at this huge water conserving option.” The findings on how these plants have adapted matters greatly in a water-stressed environment. “Droughts are making it super relevant…most people focus on drought resistance without looking at how photosynthetic pathways might be (one source of water conservation).”

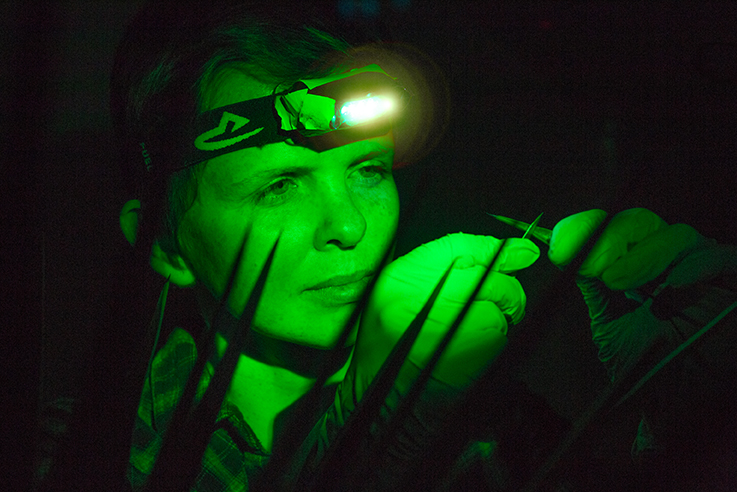

To look at the petite Heyduk, who describes herself as an active science promoter, you might think she spends her nights dancing—another favorite avocation. She moves with spritely grace. But instead, she is often found at late hours conducting research inside a greenhouse, taking measurements of plants throughout various cycles. Heyduk’s work with a Yucca hybrid native to the southeastern U.S. allows her to look at the evolution of the plant’s photosynthesis. Her research integrates evolutionary genetics, genomics and bioinformatics.

The plants do their water-conserving breath-holding on an unforgiving schedule.

“I’m monitoring a plant—a different sort of photosynthesis— taking in carbon monoxide at night. So, to see this variation and study how these plants respond to an increase in night stress, I have to take measurements every four hours.”

When not scrutinizing plants inside a greenhouse at odd hours of the night, Heyduk uses her free time to volunteer at a local middle school, teaching children about science. The volunteer experience began thanks to a friend.

Fellow scientist, Stephanie Pearl (see the Fall 2014 issue of the Graduate School Magazine) was one of the original founders of the Athens Science Café. Pearl was also involved with Hilsman Middle School in Clarke County, and encouraged Heyduk to join.

“When she was almost in her last year of graduate school, I took over because nobody else stepped up,” says Heyduk. Four years later, Heyduk still volunteers along with a group of fellow graduate students in plant genetics. “We go to a seventh grade agri-science class weekly, from winter to spring.” Topics the volunteers teach are usually plant biology-driven subject matter. “We talk about plant anatomy biomes, etc.”

The children’s teacher initiated the planting of an outdoor garden. “Dr. Stratton, their teacher, embraces the idea of kids embracing agriculture,” says Heyduk.

The following information is provided by Heyduk:

1) I cut leaf samples and use them for RNA analysis. This gives us an idea of what genes are expressed in that tissue at the time I harvested them.

2) I take gas measurements because it tells us when the plant is conducting gas exchange – CO2 into the leaf, water vapour out. For C3 plants, this happens during the day. For CAM plants, gas exchange happens at night. Gas exchange patterns are a way for us to assess whether a plant is C3 or CAM.

3) Green light is needed at night because plant stomata (pores on the leaves that allow for gases to enter and exit) respond to blue and red light. Plants are green to us because they reflect green light back while absorbing red and blue! To avoid stomatal opening, we keep to green lights. A key trait of CAM photosynthesis is that plants take up carbon at night and fix it then, as opposed to doing it during the daytime, like C3 plants. Because CAM is active at night, we have to check for gas exchange and gene expression throughout the day/night cycle to capture both C3 and CAM traits.

- Karolina Heyduk conducting research in growth chamber in both night and daylight conditions.

- Karolina Heyduk conducting research in growth chamber in both night and daylight conditions.

PHOTOSYNTHESIZING A NEW CAREER

Heyduk’s parents immigrated to the U.S. from communist Poland in the 1980s after her father sought and received asylum. Her father had a doctorate in philosophy, and her mother was a chemist. She began her formal education at the University of Wisconsin in the field of economics.

Although Heyduk’s mother worked in a laboratory, she was also a gardener and frequently outdoors. Heyduk took a job which changed her career course. “I had always had an interest in a natural environment…had this random job with an entomology prof looking at something like potato beetles…outside, hot, but I loved it…in the fall, I applied for a job at the USDA.”

And as for changing course of study, Heyduk discovered that her own evolutionary timeline has worked well. She finds that having begun in another discipline is an advantage, in that it allows her to view things from a different perspective. “A lot of people scoff at the non (science) majors…but it gets me to think about how people perceive science,” she explains.

Heyduk adds, “I think my research is relatable because I say I am working on photosynthesis.”

She breaks down the research in lay terms: “I’m monitoring yucca plants for a different sort of photosynthesis. The plants under study take in carbon dioxide at night. So to see this variation and study how these plants respond to an increase in night stress, I have to take measurements every four hours…I do this every other day so that I can sleep.”

The project runs for 10-day cycles, which she has done five times in the past year and studied 50 plants. The sabal palm was her focus during the first two years. The plants are all maintained within a controlled setting on the UGA campus inside the plant biology greenhouse.

“My advisor had me dive headfirst into research,” Heyduk says. “I didn’t know anything about programming or bioinformatics…and it has been surprisingly fruitful.”

Do plants evolve as slowly as people? Heyduk thinks “it might be faster because plants cannot affect their environments.”

In contrast, Heyduk seems to have fully adapted to life in the Deep South in short order. She says she much prefers the Georgia heat versus the Wisconsin cold, even when she is deep inside a greenhouse in the summer. But during winter months, the scientist must conduct research inside a cooling greenhouse. So be it.

On a frosty January morning after a long night of monitoring the yucca plants, Heyduk shivered slightly and pulled her sweater around her.

“It’s really hot in the day, but was 65 degrees inside the greenhouse last night,” she announced. Heyduk married a fellow plant biologist last July on a farm outside Watkinsville, Ga. She will finish her doctoral work in May of 2016, but plans to remain at UGA for postdoctoral research.

“The last cycle I finished was the last one for my dissertation. My professor got a bigger grant to do more of this.”

Her dreams have synthesized; now she, too, can breathe.

Agave plants – photographed through light painting.

#41 Agave american (huge/long with yellow stripes)

#44 Yucca aloifolia

Postscript:

Karolina Heyduk was selected to attend the Graduate School’s Emerging Leader’s workshop in the fall of 2014. Emerging Leaders is a prestigious leadership opportunity for outstanding scholars who are recommended by their professors. “I loved it,” says Heyduk. I learned more about how to interact with the world around you. And I set goals for myself.”