Chickens, Computers And Science

By: Cynthia Adams

When James Carmon, a professor in animal husbandry, convinced UGA to buy the most expensive and sophisticated computing equipment available, UGA soon joined the space race.

What might chickens, computers and UGA have to do with the Apollo 11 mission in 1969?

The answer is twofold. Call it a matter of synchronicity.

According to NASA Planetary Protection scientist Moogega Stricker, chickens were fed moon rocks in order to verify their safety to humans prior to their becoming available.

“I’m not sure why they selected chickens, but it’s just one of those tests,” she said on the Freakanomics radio program aired June 5 last year. “How do you prove that you’re not going to kill anybody?”

A UGA researcher studying chickens is a reason Georgia has direct ties to the Space Race culminating in the Apollo 11. The story appeared first in a documentary, “50 Years of Computing at the University of Georgia – 1957 to 2007” which aired in 2016. Last year, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution effectively trussed up the chicken connection that must be re-told.

Apollo 11 liftoff from launch tower camera (photo: NSSDC.GSFC.NASA.GOV)

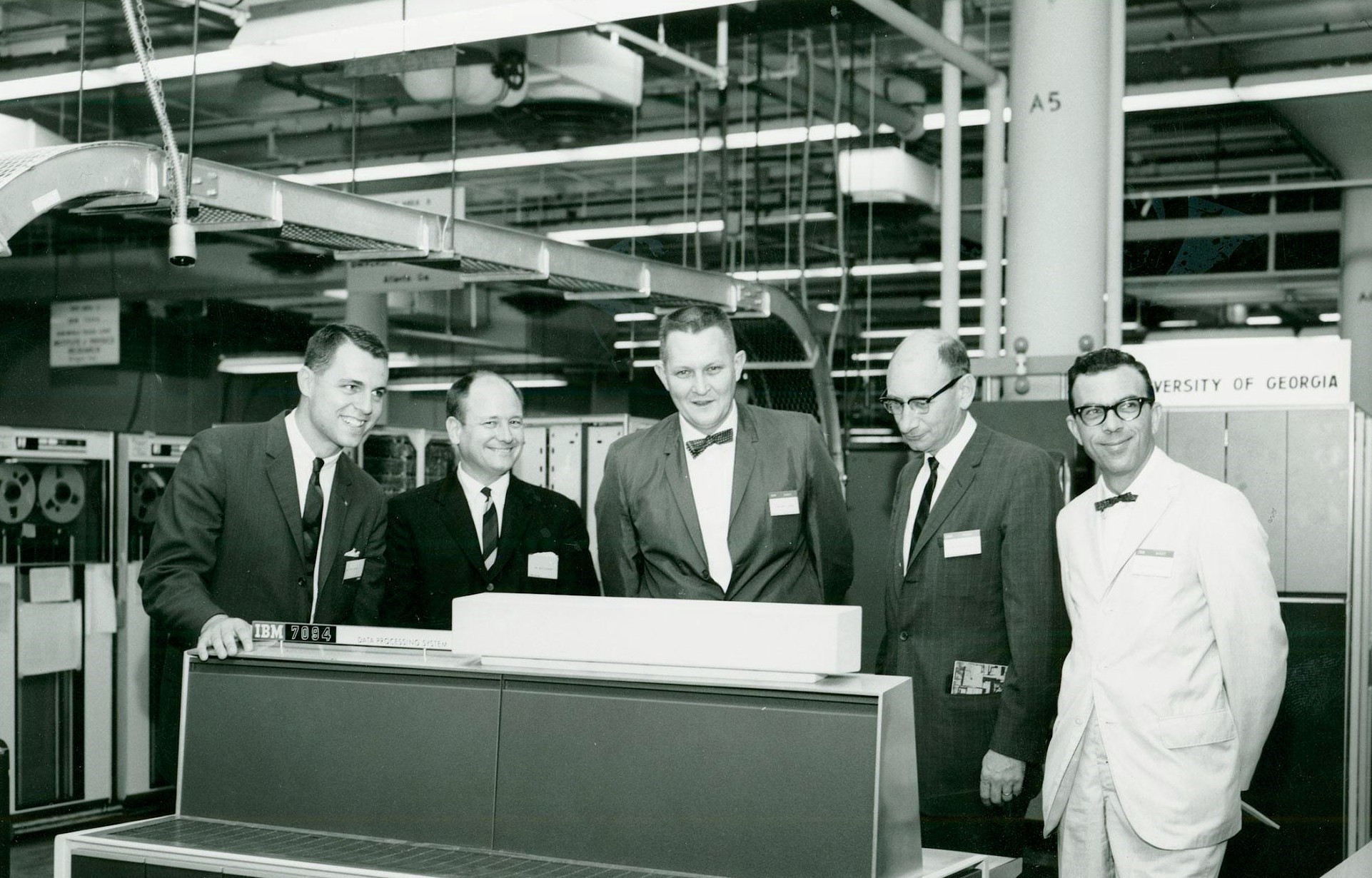

The UGA researcher in question, James L Carmon, loved statistics even more than chickens, his research subject. The professor was fascinated by statistical analysis according to his family. The IBM 7094 mainframe was a rarity, especially on college campuses, but Carmon made it his vision quest to bring one to Georgia.

Such a computer (although bulky and one which overheated easily) was critical to analyzing huge amounts of data.

The year was 1964, when the IBM 7094 mainframe was certainly not chickenfeed to purchase; writer Bo Emerson reports it cost $3 million. A sum, he adds, which would be roughly equivalent to $25 million today.

Carmon apparently possessed superior negotiation skills in addition to his statistical talents.

The professor of animal husbandry (incidentally, specializing in broiler chickens), thereby played his part in getting man to the moon. Carmon persuaded UGA to buy what Emerson called “the biggest, costliest computer in existence.”

Somehow, UGA found the scratch to make it happen, despite the astonishing costs.

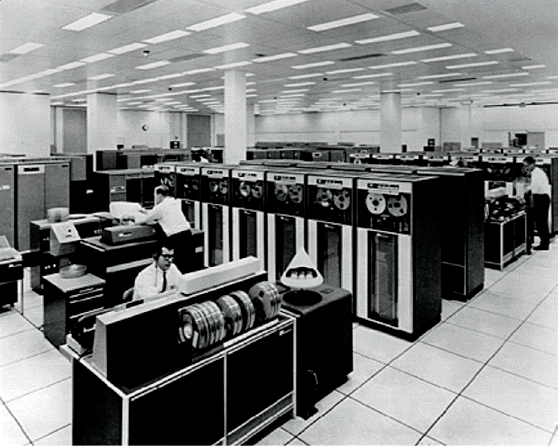

The 7094 was IBM’s last commercial scientific mainframe, built for large-scale scientific computing. It “achieved expanded power through high-speed processing” according to IBM’s website. IBM customers could convert from the 7090 machines to the 7094 data processing system in hours.

Truly, it was large-scale.

Such a machine as the 7094 filled entire rooms dedicated to data processing. The mainframe had “36- bit memory with four petabytes,” says retired UGA employee Harold Pritchett who worked with the 7094, “a total of 40 of these grids. Each had 4,096 doughnuts. So, a 36-word memory rate was about 6” square and 2.5” long…”

Translation: it was a monster.

The IBM 7094 was located in the basement of the Lumpkin House on the UGA campus.

The IBM mainframe was so enormous that controllers had to be suspended from the ceiling when it was installed in the basement of the Lumpkin House.

According to former employees, the machine was paid for by renting time out to various agencies and entities, including NASA. It was one of few in the Southeast outside NASA’s own facilities. The computing center also sold time on the 7094 to then Lockheed Marietta.

James Carmon, center, shown with the IBM mainframe computer. An IBM 7094 at UGA was a source of major computing power and important to expediting calculations. (Photo: UGA Archives)

NASA employees traveled to Athens from Huntsville, Ala.

When NASA’s team arrived, they threw everybody out. “They brought their own operators, their own tapes,” the documentary explained.

“Keep in mind that the IBM machine had a memory of between 32 and 150 kilobytes, or one-millionth the capacity of your iPhone, and was programmed with the use of punch cards. Hundreds of punch cards might be necessary for a single program,” wrote Emerson.

When the machine was eventually decommissioned, it was stripped for valuable parts and the rest was trashed. It was an inglorious end for a machine that had played a part in the quest to place man on the moon.

IBM 7094 System (Photo: Columbia.edu)

“Harold Pritchett, who worked in the computer center, still has a cast-off piece of the computer’s central memory core in his Athens basement,” wrote Emerson. “The hand-made interior features thousands of pin-head sized ferrules, strung on wires. ‘It’s history,’ said Pritchett.”

He added, “But it’s forgotten history, except in a few corners of our cultural memory.”

Forgotten, too, is poultry’s immeasurable contribution to both scientific endeavors, and, incidentally, to planetary safety.

Mission Control celebrates Apollo 11 (photo: UGA.EDU)