A Man with a Fiduciary Mission: Michael Gene Thomas

By: Cynthia Adams | Photos By: Nancy Evelyn

To meet Michael Gene Thomas, whose warm, kindly smile and frequent laugh are signatures, is to meet an outwardly easygoing man. But inwardly, Thomas is a doctoral student in the College of Family and Consumer Sciences, one driven to make a meaning in the lives of those with the least financial resources. He cares about ensuring that vulnerable populations have access to financial planning services—a resource that only the affluent usually enjoy.

For a money man like Thomas, this is a tall order but one he feels suited to deliver. His background (a 2005 degree in accountancy and two years working at a CPA firm) made for an easy transition into working in college admissions and later, as a financial aid planner, at LaGrange College.

What was glaringly obvious to him was that the true work of a college was transformation. For many of the students Thomas helped, he realized this meant transforming their relationships with their money. Credit cards and student debts were sometimes strangling. As students sank into debt, dreams became more of a distant reality.

Cold hard cash—and equally cold, sometimes hard, facts—are in order.

Financial Literacy is the ability to understand how money works in the world: how someone manages to earn or make it, how that person manages it, how he/she invests it and how that person donates it to help others.

For many, straightening out financial relationships is as complicated, or more so, than untangling our interpersonal ones. According to the website Nerdwallet, the cost of living has consistently outstripped earnings for many. And worse, card holders often either don’t know their credit card debt or underreport it. Yet they write that in 2015, average household debt was nearly $130,000-with $15,355 of it on credit cards.

Thomas takes an old-fashioned approach to a newfangled problem. That problem is, first and last, the problem of debt, which is the outcome of financial illiteracy. Most Americans have little or inadequate savings, let alone investment capital. He would change that, and thinks there is good reason to begin teaching the value of a dollar sooner than later. The “Millionaire Next Door” approach, wherein people deliberately live beneath their means, is one way of summarizing his financial philosophy.

Thomas, who drives a 10-year-old car (“I hope to get to 500,000 miles,” he declares) is serious about becoming such a millionaire. He tightens his belt—actually, he cinches it—and refuses to be drawn into impulsive buys, ones he might repent at leisure.

Admittedly, says Thomas, living below one’s means is not an easy sell. “My friends tease me about that car” he says. He simply ignores them.

Financial illiteracy is something which surfaces like many social dysfunctions, as almost organic. Too often, he says, it is denied or ignored by a social construction created to protect our images.

Thomas was born into a military family which taught him principles of self-discipline. “My father was a Marine, and I began school in Oahu.” The family moved to Jackson, NC before eventually moving to Gary, In. There, he fell in love with the game of baseball. While attending a Florida baseball camp during his junior year of high school he learned about LaGrange College. He decided to ultimately attend LaGrange and earned a degree in accounting there in 2005. Afterward, Thomas worked in a CPA firm for two years. Later, he was hired at LaGrange as an admissions counselor.

Thomas’s eventual experiences as an auditor, and as LaGrange’s director of affordability and family financial aid planning, made him privy to deeper insights. Some of the students’ financial issues were especially worrying.

“I served in various roles at the college. I saw how vital each function was to transform the lives of the students it served. Going through those conversations, those vulnerable conversations, really hit home for me that the work I wanted to do has to happen far before that year and a half you really get to work with families.”

He felt he needed to initiate conversations about finances earlier—as in, well before a student began to apply to colleges. He explains, “As an auditor, I felt isolated. And as a financial aid person, I felt we had a very short window of time to help families.” This led Thomas to apply to UGA’s financial planning program in the College of Financial Planning, Housing and Consumer Economics.

Thomas had found his footing and became involved in professional initiatives within the College. “My biggest accomplishment was helping to create the first financial literacy summer camp for middle school students at UGA.” He had also launched a business, Modom Financial Services. He describes Modom as based upon a different premise, aiming to financially empower the underserved, especially youth and couples.

“I don’t want to get to my finish line alone,” he says. His eyes are focused, determined. “The reason I am pursuing a financial planning degree is that I want to provide services to the underserved and to the (needy).” Thomas rejects a topdown social perspective. “I am not blessed because I have something someone else does not have.”

Complicating the work he does, he says that it doesn’t help that money and finance are so difficult to discuss.We learn early on that money is one of society’s big taboo subjects, Thomas adds wryly. We don’t disclose financial information easily and too often only when we have no other choice, he says. This further insulates us from making realistic, healthier choices before we are at a crisis point.

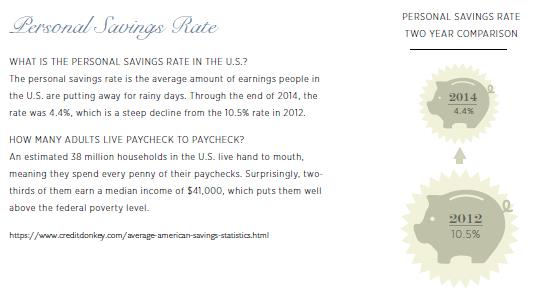

An estimated 38 million households in the U.S. live paycheck to paycheck. Baby Boomers tend to do better when it comes to hanging on to their extra money. Adults aged 55 and older have a positive personal savings rate of about 13%. Millennials(adults 35 and under) have a personal savings rate of negative 2%. Between high student loan debt and stagnating wages, saving at all proves impossible for many of them.

As one popular book on personal finances says on the cover, being educated about our finances is a case of “Your Money or Your Life.” Debt and lack quickly strangle dreams and purpose. Life dreams become thwarted.

Money – A More Loaded Subject than Sex?

Why, precisely, is money such a psychologically loaded subject? Thomas smiles at the question thoughtfully before answering. He sits in a lobby near campus while nursing a coffee, discussing what he has learned through his various clients (both at Modom and the UGA programs he is involved with) struggling with money issues.

He wears a crisply laundered dress shirt and pants, but sports no logos. He is a man who has learned to practice what he preaches: Keep things simple. Live simply. He sighs, looking into his cup. Like Warren Buffett, the famous money man popularly known as the Oracle of Omaha, Thomas is also pragmatic and imminently kind.

Money and personal finance, he explains, are a complicated, loaded set of subjects.

“If somebody runs into money, (like a windfall) it emphasizes certain traits about them,” says Thomas. He shares what he has learned through Modom Financial Services, and the clients struggling with money issues he served both there and through the collegiate programs.

What he has learned in working through financial challenges doesn’t make him a seer, but it makes him privy to deeply held secrets and issues. “If they have an addiction problem it magnifies it…money magnifies personal qualities. Whether we realize it or not, money is a genuine expression of whom we are.” Here, Thomas pauses for emphasis.

“If you want to know something about somebody, look at their bank statements,” he says seriously. He even suggests that couples might want to look at one another’s bank statements before they become too involved. “That would be revealing,” he says, arching a brow elaborating. In fact, he doesn’t talk about market fluctuations or how to beat inflation. He talks about things such as financial infidelity and trust issues—chief among other issues that entangle our financial truths.

“I’ve talked with couples in the past, but neither knows what the other is doing with their money. Money tells a story, another picture of our truer selves. There is a deep connection with who we are, intrinsically, and how we spend.”

Thomas firmly believes that you can tell a lot about a person if you observe how they spend their money. “If people went out and asked to see their bank statement you could learn a lot about that person…it should be explored a little.” His eyes widen. He is serious. Money, he stresses, is a serious subject.

“We’ll talk about sex, we’ll talk about drugs. Everything. But it—money—is very difficult; money is very personal. We will talk about sex before money.”

To know thyself, Thomas adds, you should begin with full self-disclosure with the intimates in your life. “A great question before dating or befriending someone would be: “What role does money play in your life?””

Thomas says people are burdened with unexpressed discomfort and expectations concerning money. Basically, money actually makes our worlds tilt off axle, especially if we cannot talk openly about it, he notes. When asked if he, himself, has a healthy relationship with money, Thomas weighs the question. He replies that he is constantly learning and evaluating himself, too.

“Getting your house in order isn’t a once and done…you keep altering it,” he explains.

“There are some things I’m working on… For me, my biggest thing is that I don’t take enough (financial) risk. I understand the markets. I talk about my money plan.” He frowns slightly. Perhaps he is too cautious, he wonders aloud. “Too much of a saver?”

The Ultimate “Exit” Plan…

But Thomas has had to sort through the financial issue of owning a home that is in a neighborhood with declining worth. In real estate terms, he is upside down—the property is losing rather than gaining in value—but he refuses to declare bankruptcy. Perhaps instead, he and his wife will consider a short sale—an alternative that he finds more ethical. He further discusses short sales, and the complicating notion of a house versus a home—something with lingering financial implications for an entire family. Thomas has gone so far as to stipulate that his children liquidate the family home when he dies. A home can become a burden to offspring, he says. “I don’t want to pass the baton back to them,” he says, “and make them have to be (slowed) by us.”

Millennials have embraced an altogether different scenario of home ownership. Their affection for tiny houses (ones built upon an axle, sometimes repurposed from shipping containers, and therefore more affordable) have become part of a social movement. It is attractive to simplify one’s life and shrink a mortgage, Thomas notes. “We can use money as energy to do other things (than pay a mortgage)…these things can be more meaningful than buying a new pair of shoes or the latest iPhone.”

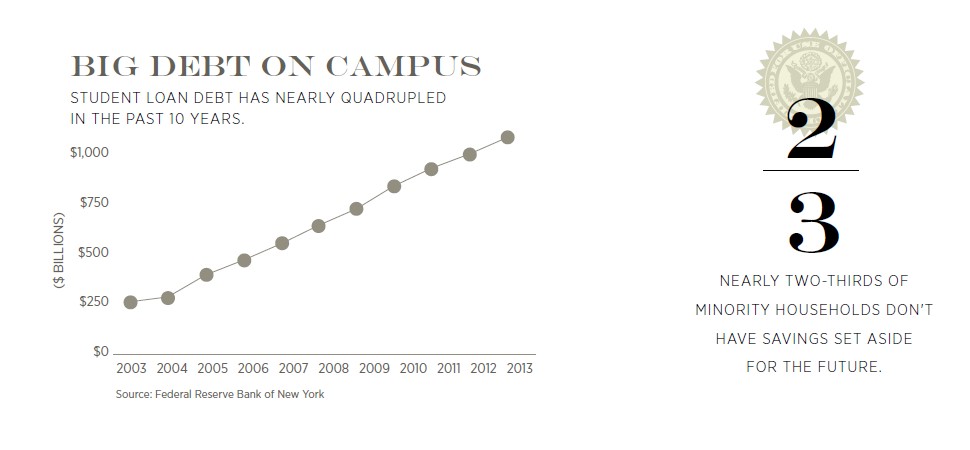

The amount of total student loan debt has soared in the past decade, shooting up from $240 billion at the start of 2003 to nearly $1 trillion today.

A Humbling Loss and the Aftermath

Psychological issues have been especially difficult for Thomas since November of 2015, when he had to face down tragedy within his family. His sister, Tiara Thomas, was murdered just before Thanksgiving, allegedly by her ex-boyfriend, leaving three young children behind. Thomas has since been trying to help his young niece and nephews navigate a nightmare while coping with his own sense of bereavement.

Thomas was close to his sister; he is deeply shaken and the grief is unspeakable. “Now I know there is nothing worse that can happen to me. Nothing that can make me feel as low,” he says quietly during the week before Christmas. Thomas says his emotions spill over into his work, leaving him less hesitant or concerned about small things. “I am now absolutely okay with risks, but they have to be calculated.”

His sister’s untimely, tragic death was gravely humbling. “We still mean something even though we are but a small piece of the big whole,” he says thoughtful. The enormity of what he has experienced has changed him. “I think it is a breakthrough. At the end of the day, I am intentional about doing my very best, and if it doesn’t happen, guess what? I’m probably going to have another opportunity to do it better…everyday, we have an opportunity to do it better.”

Thomas, ordinarily an optimist, is finding a new philosophy to navigate through tragedy. His new philosophy, he has discovered, “is about living in the moment and relaxing into the grand experiment that our lives become. If something were to happen to me tomorrow, someone whom I might not have a great relationship with may decide to speak at my funeral…people will determine to remember me how they wish.” An aunt, one who spent her life in the military, told Thomas to stay true to his convictions. “That was it,” he repeats softly. That straightforward advice became a sort of lodestar.

Thomas, ordinarily an optimist, is finding a new philosophy to navigate through tragedy. His new philosophy, he has discovered, “is about living in the moment and relaxing into the grand experiment that our lives become. If something were to happen to me tomorrow, someone whom I might not have a great relationship with may decide to speak at my funeral…people will determine to remember me how they wish.” An aunt, one who spent her life in the military, told Thomas to stay true to his convictions. “That was it,” he repeats softly. That straightforward advice became a sort of lodestar.

He is actively building his own legacy. Thomas volunteers with low income tax assistance and with the Athens work release program through UGA’s Aspire clinic. With the assistance of other UGA undergraduate students, Aspire provides six or seven sessions to the prisoners, designed to help them achieve more financial ability and prevent recidivism. Thomas believes that in supporting prisoners’ access to services and benefits, it will make for a healthier transition to freedom. “There are so many ways to help people plan.”

He is actively building his own legacy. Thomas volunteers with low income tax assistance and with the Athens work release program through UGA’s Aspire clinic. With the assistance of other UGA undergraduate students, Aspire provides six or seven sessions to the prisoners, designed to help them achieve more financial ability and prevent recidivism. Thomas believes that in supporting prisoners’ access to services and benefits, it will make for a healthier transition to freedom. “There are so many ways to help people plan.”

After he completes his program, Thomas is leaning towards working with a local agency. One, he adds, that has a firm and strong commitment to service.

“For me, being in the doctoral program, and aspiring to do the kind of work I do to stay true to my convictions, is keeping me focused. Dr. Goetz and Dr. Palmer, members of the multidisciplinary Healthy Marriage and Relationship Education (HMRE) team, were gracious enough to allow me to be a part of this project. The HMRE project, will impact a lot of lives. It takes into consideration relationship dynamics, communication, family, therapy, best practices, and the financial capability of this component, working together to create more stable families—emotionally, psychologically, and communicate better. That is the kind of work I want to be doing. How do we strengthen families?”

Thomas says absent that helping aspect, he would have simply completed his master’s degree and immersed himself in a new professional track. “If this hadn’t happened, I’m not sure I would have done a doctoral program.”

And so Thomas, even in the midst of personal grief, finds meaning in eliminating financial difficulty. He works with the poorest, the broke and broken, the imprisoned, and the most disenfranchised. “Love when it is inconvenient,” he adds softly. Thomas writes this online, a sort of personal manifesto, which is a declaration of his integrity:

“All people need is for somebody sitting across from them at that desk to care about them. Let’s show people we care about them, and let’s start there. Then we look at assumptions and race, and can be sensitive to how we talk to them. If we don’t care, you’ve just given me a script.”

For Further Reading:

Thomas’s friends have set up a fund for his surviving niece and nephews at: Gofundme.com/tiarathomas

To learn about ASPIRE

For additional information concerning the HMRE project