Stephanie Jones

By: Cynthia Adams | Photos By: Nancy Evelyn

“This was about African-Americans, this was about literacy, this was about education…I needed to do this.” – Stephanie Jones, Graduate Student, UGA College of Education

Stephanie Jones credits a happy accident with falling into an absorbing research venture. Possibly due to the fact that a faculty member on campus shares the same first and last name—Jones received a general announcement e-mail from the College for Environmental Design, or CED. The email, which immediately grabbed her interest, concerned a charrette (more later on what that is) to be held at the site of the former Boggs Academy in southeastern Georgia. As she read, Jones realized that, by a stroke of fate, she was destined to become involved.

The former Atlanta high school English teacher (also the Stephanie Jones distinguished by the middle name “Patrice”) read just enough of the email to hit reply. She was joining the CED experience. Then, Jones began researching exactly what she had just gotten herself into. First of all, she wanted to know everything about Boggs Academy. (She learned that it was an historic boarding school for African-Americans with an astonishingly low profile located in Keysville, Ga.)

Secondly, Jones wanted to know what the heck a charrette was. (In essence, it is a very compressed research experience.) As a graduate student in the College of Education, one who studies literacy and education, the term was new to her despite her strong vocabulary.

Without hesitation, Jones cleared her schedule.

CED was equally delighted—they could use an educator in the mix with three of their own graduate students to strong advantage.

Afterward, Jones says the charrette at Boggs changed preconceived ideas about education in the Deep South then and now.

She speaks admiringly of the multi-racial faculty at Boggs and how innovative the Academy was: “I still would love to be affiliated with this remarkable place.”

THE WORD CHARRETTE—unless you are a designer or are French—probably doesn’t ring a bell. But it does ring a bell for any student in UGA’s College of Environment and Design. The word is at the heart of an experience that is succinct, intense, and fiercely deadline-oriented, by deliberate design.

As Jennifer Lewis, who works in CED, explains, the literal definition of the French word charrette translates into “little cart”. And—wait for it—there’s an actual bell involved.

The idea of a charrette was coined by Parisian architecture professors whose assistants would push a little cart through the studio between the drafting tables when a project was due or a model was due. A bell signaled that time was up as assistants collected students’ work.

Lewis says, “Hearing the cart coming, trying to finish a project, helped develop a public design project in a compressed amount of time—operating on the theory that some of us do our best work under pressure.”

As coordinator for the Center for Community Design & Preservation, it is Lewis’s job to match community needs within Georgia with available resources at CED. She also coordinates design charrettes.

Charrettes are great planning exercises, Lewis says, with discrete boundaries of time and energies. The school offers two each semester. (In the winter 2012 Graduate School Magazine we covered a charrette at historic Stratford Hall on the James River in Virginia.)

“If you commit to this project (ours is three days long) at some point in the process, everybody needs to clear their desk, come to the place they are working and dedicate themselves.”

Designers, the public, stakeholders, and students break off and come back together as they work through a project, or charrette. “Through this, we have a clear beginning point and end point,” she explains.

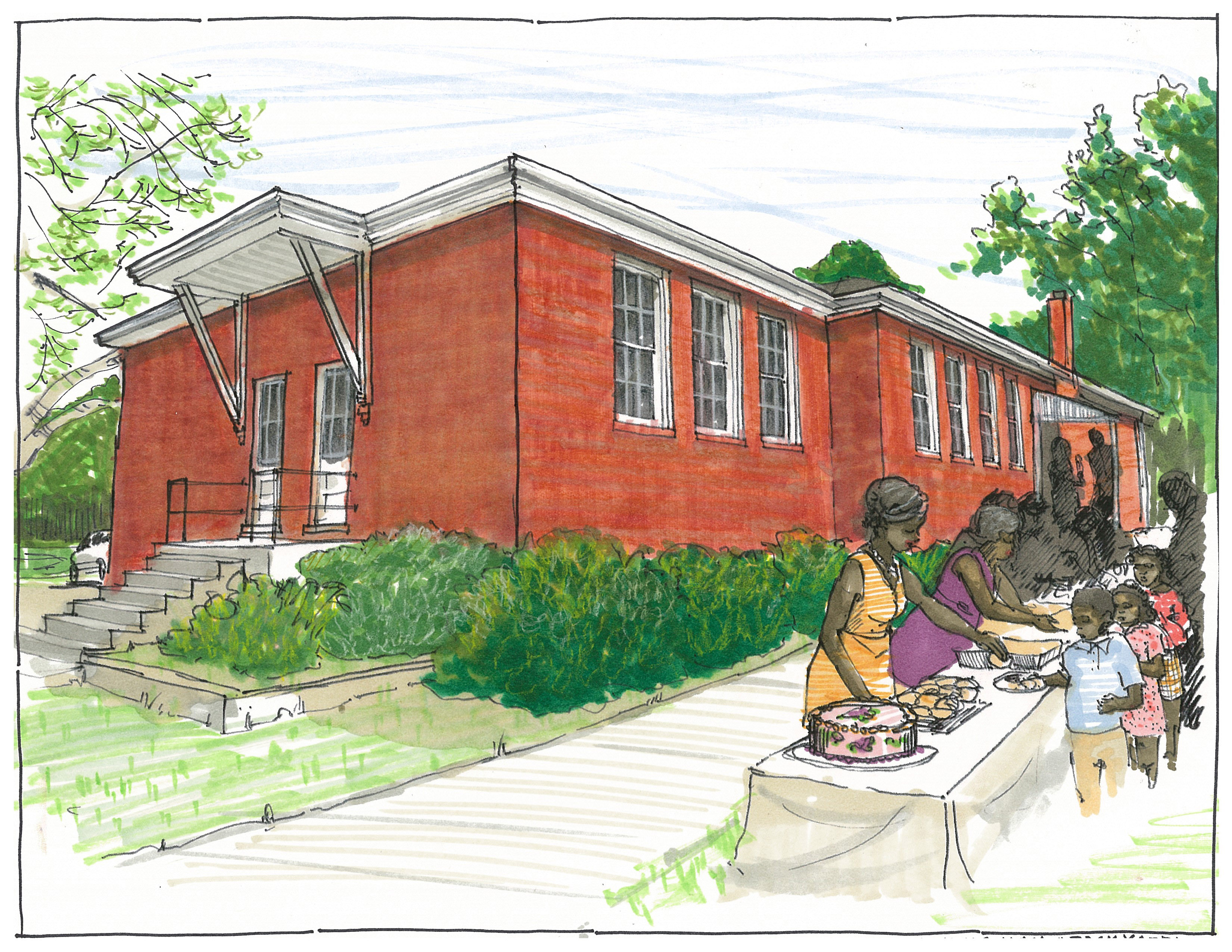

UGA’s Graduate School Magazine became interested in the extraordinary charrette which took place at historic Boggs Academy in April—a merger of interdisciplinary research, community service, outreach, and pooled resources. Plus, the former Boggs Academy, now reinvented as the Boggs Rural Life Center, provided for a charrette encapsulating an amazing aspect of post-Civil War education.

THE STORY OF BOGGS ACADEMY

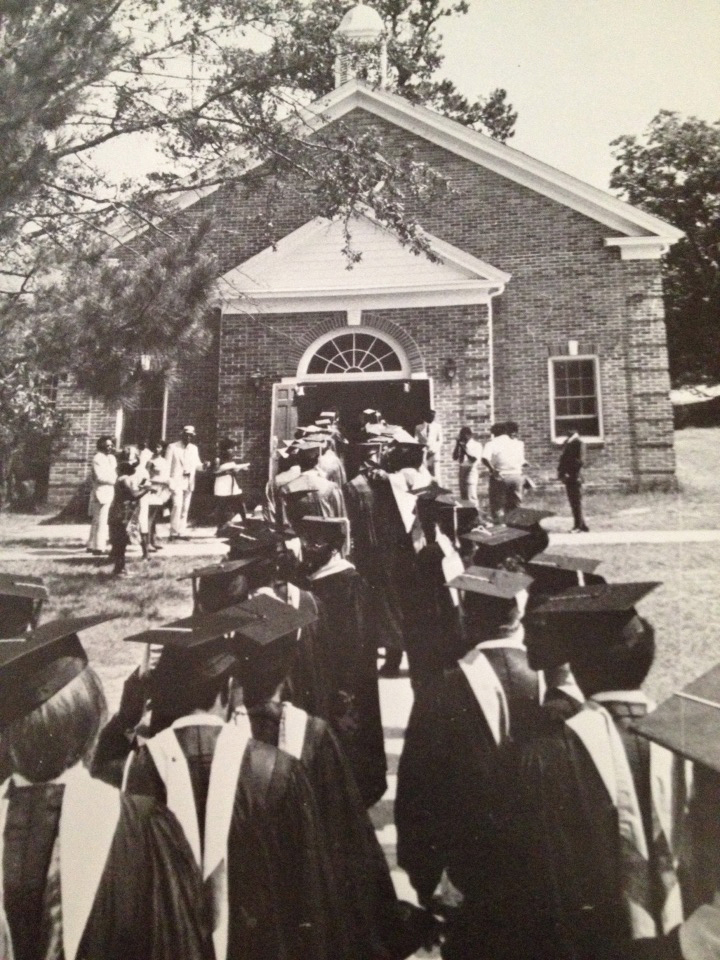

Boggs Academy operated from 1906 to 1986. The last class graduated in 1984, as the school’s purpose changed with integration.

The school was founded and operated by the Presbyterian Board of Missions for Freedmen, a committee organized in the final year of the Civil War. The mission, largely supported by women, anticipated the educational needs of thousands of African-American children. Boggs Academy was created because public schools remained stubbornly segregated after the Civil War. As a whole, the educational needs for African-American children were ill met, if at all, unless provided for by private charitable interests. (Only one black school existed in all of Burke County, Ga.)

Boggs Academy was prompted by the desperate need for educational opportunities within Burke, which mirrored the needs throughout the entire South.

Founded by the Reverend Dr. John Lawrence Phelps, both a church and school were built upon two acres of donated land in Keysville, Ga. Only five children entered Boggs Academy when the school opened its doors in early 1907. It was initially concerned with providing education to local students, but later became a popular preparatory school for students throughout the Southeast.

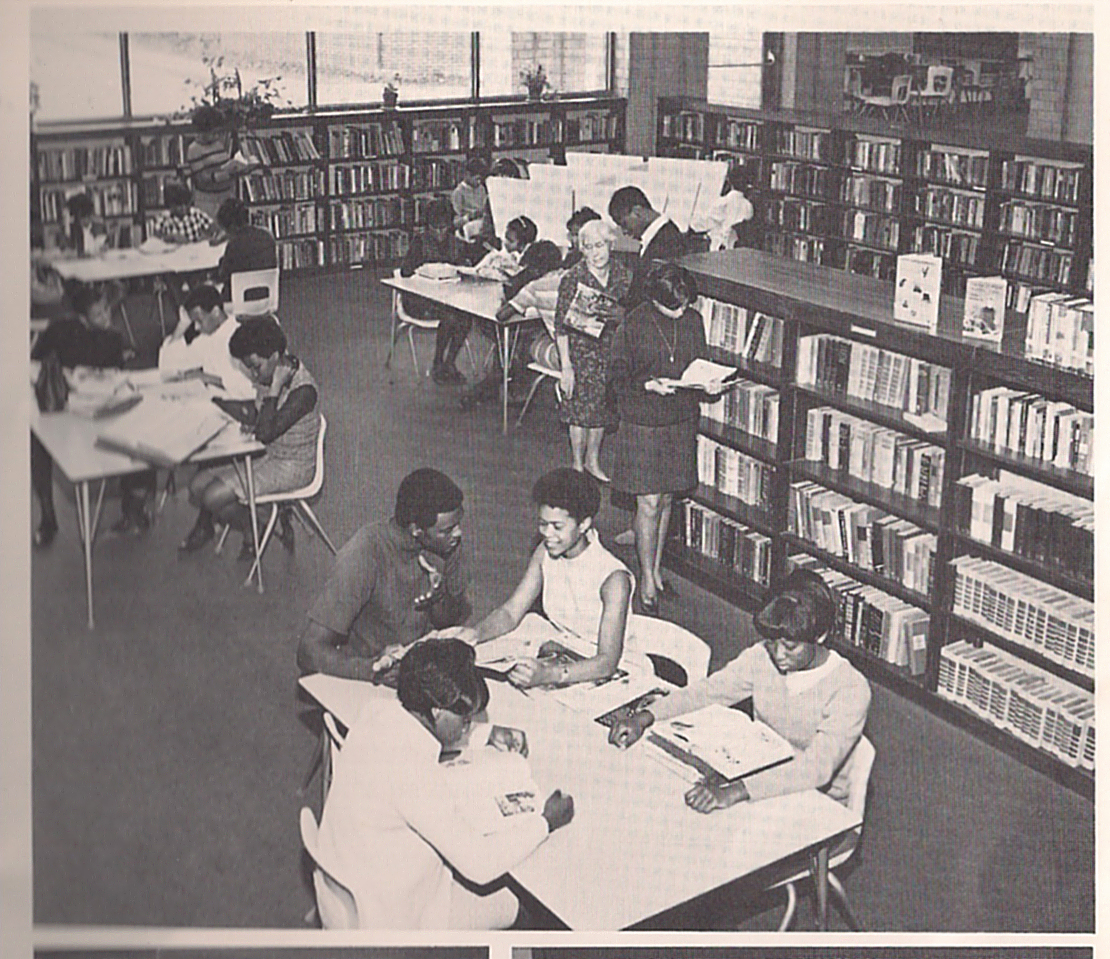

“It afforded people opportunity to get an education. Middle class and professional black families had no place to send their children,” says Jones. Over the years, the Boggs student body and campus flourished with additional acreage, buildings and capabilities. Eventually it encompassed a complex of industries that supported the school, with a work/study program teaching skills like farming and food canning. They also taught social skills and graces along with academics.

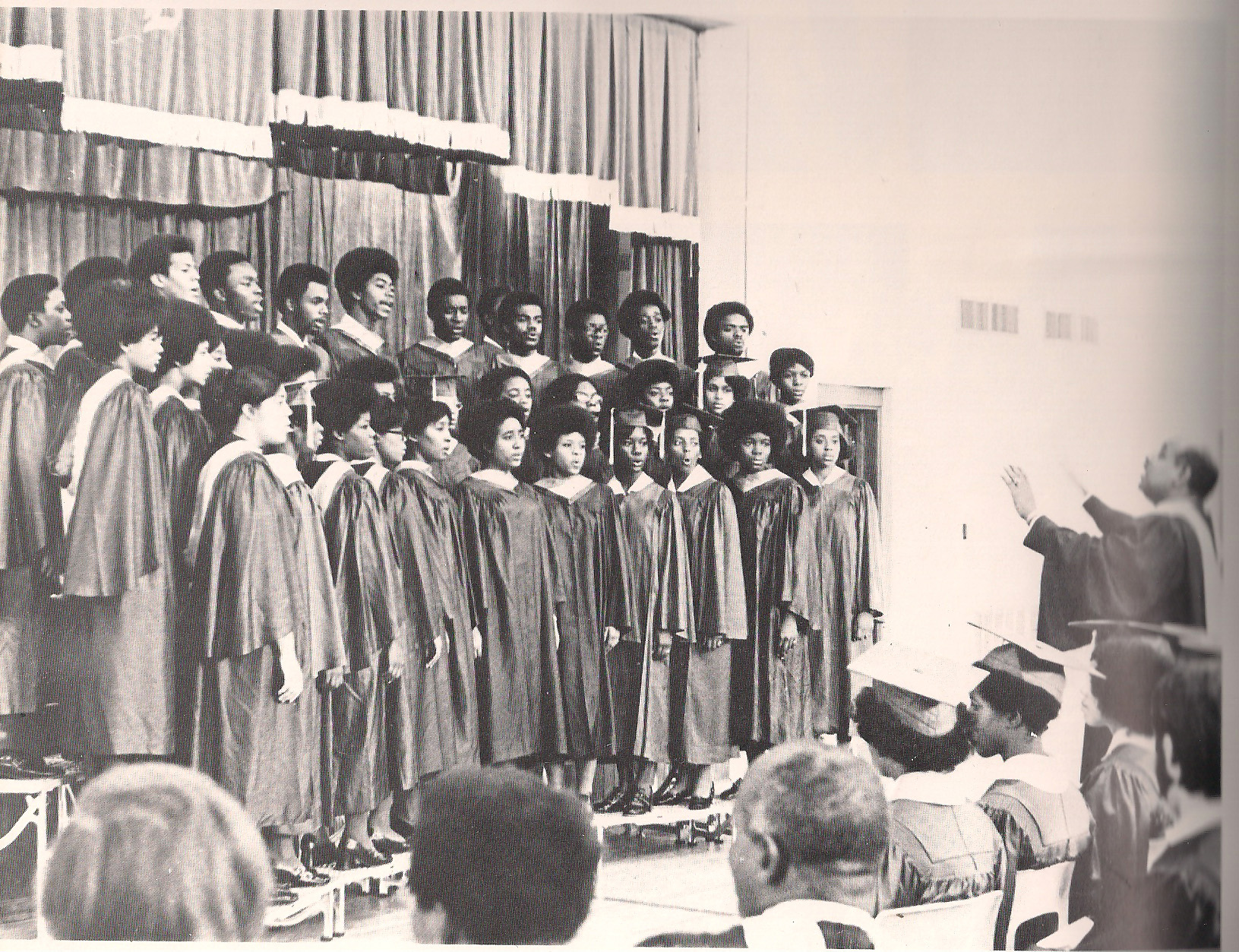

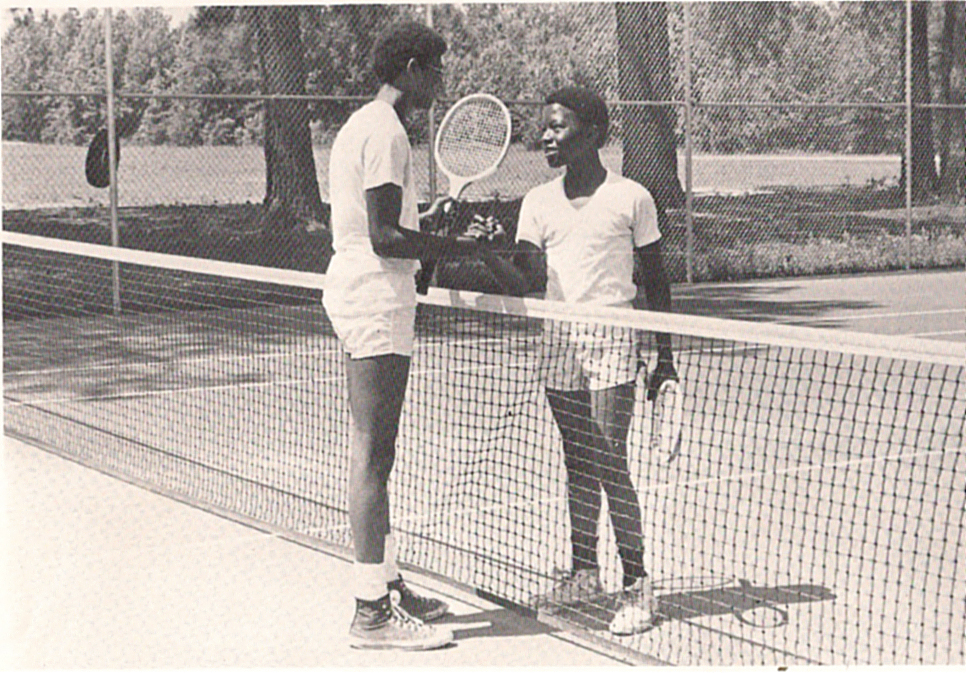

“The teachers had high expectations of the students,” Jones adds. “They were expected to get A’s in everything.” The students also learned sports, music and other arts.

When Boggs Academy closed in the late 1980s, the U.S. Presbyterian Church Association worked to transition the school to an organization that still fit its original mission. The Academy morphed into the Boggs Rural Life Center.

“Hearing the cart coming, trying to finish a project, helped develop a public design project in a compressed amount of time — operating on the theory that some of us do our best work under pressure.” – Jennifer Lewier, UGA Center for Community Design & Preservation

“AN INFINITE LABORATORY”

Ovita Thornton is executive director of the Georgia Clients Council, or GCC. GCC provides public assistance to disenfranchised communities statewide. She first became aware of Boggs 13 years ago, serving initially as a resource person. Thornton was not a Boggs alumnus, but is completing a term this year as president of the board of Boggs Rural Life Center.

She met Pratt Cassity, director of Public Service and Outreach at CED, when they worked together on a corridor planning project years earlier. Last fall, Thornton contacted Cassity, this time with a different project in mind. She solicited the help of the CED to create a cohesive vision for the Boggs Rural Life Center. Thornton ultimately led Cassity to examine the former Boggs Academy as a potential charrette.

Present-day Boggs faced the dual challenge of forging a new identity while maintaining its historic legacy and chartered covenant with the church. In a truly rural, sparsely populated setting, the alumni and board members were struggling to redefine themselves as an organization and find a way to meet their defining mission: to help people in need.

Thornton was interested in Boggs’ mission, which overlay with that of GCC, one of the oldest grassroots organizations. “It is through my job that I can share my contacts, build new collaborations, provide training, assistance—and write grants and find funding for Boggs,” she says. Thornton estimates that 90 percent of the resources paired with Boggs are due to the GCC. Her colleague, Jackie Bosby, has helped create a museum at Boggs.

“I assumed the position as board president because there were internal things needing to be addressed, but could only be addressed through a position on the board,” Thornton explains. Her goal has been to make Boggs “stable or sustainable.”

Sustainability was a complicated project to tackle. The campus alone, as it exists today, is a large property comprised of 1,200 acres. There are buildings and amenities in various states of repair. And there were two extant groups with sometimes different visions for the future. Those two groups comprised the Boggs Alumni Association and the board of the Boggs Rural Life Center.

In the past, the two groups were contentious, according to observers. They did agree on two points, however. One, the history of Boggs was not well known. And two, they had to find a new way to sustain the campus and a newer vision.

Would they become a retreat center? Should they revert to their agricultural roots? What about management and sale of the timber on the property? They needed expertise in many areas—agriculture, design, planning and education. “We (CED) had expertise to answer some of their questions,” Lewis says.

The CED faculty decided to reach out to a variety of disciplines given the challenge: how to adapt the former boarding school into a community resource? Cassity and Lewis agreed to take on Boggs as a project, finding support from the top-down after Cassity approached UGA president Jere W. Morehead last spring.

“We received generous funding for the charrette from President Jere W. Morehead’s Venture Fund and the support of our dean, Daniel Nadenicek,” says Cassity. The idea was to use a field team to gather information, something that the Kettering Foundation calls “concerns gathering,” says Cassity.

They composed a solicitation targeting a variety of UGA programs and sent the message out on list serve. The initial response to a proposed charrette at Boggs was disappointing.

One of the email recipients was Stephanie Jones, a doctoral student studying language and literacy education in the College of Education. Initially puzzled by receiving that particular email, she quickly knew why. “There is a professor in the College of Education named Stephanie Jones as well,” she says. “Now, I use my middle initial, P.”

Boggs was only a couple of hours away and yet it might as well have been on the far side of the moon—Jones had never heard of it. “I found out it was an African-American boarding school. I thought, ‘How could I not know about this place?!’ I was immediately interested.”

Jones wanted to know more about Boggs Academy. “This was a high school, and a middle school. And 90 percent of the students went on to post-secondary school, matriculating right into college!”

The idea of joining the charrette was irresistible. “This was right up my alley. This was about African-Americans, this was about literacy, this was about education…I said, ‘I’m here! I need to do this.’” Jones cleared her schedule and rearranged meetings in order to attend her first charrette.

Lewis recalls Jones’s immediate reply. “Stephanie emailed me and said, ‘I’m African-American. I’m interested in education. I’ve never even heard of this place and I want to come see it!’ And, I definitely wanted her there.”

The eventual trip to Boggs also included three CED graduate students representing each of their specializations. CED masters students included Chencheng He, a Landscape Architecture student from China, James Anderson, an Environmental Planning and Design student from Macon, Ga., and Ross Sheppard, an Historic Preservation student, from Sandersville, Ga.

As a prelude to the Boggs experience, Jones interviewed her mother about her integration experience as a young girl.

“She was involved in the second wave of students who integrated her school. The first boy and girl integrated Newton County in 1966. She went in the second wave in 1967.”

Jones was ready for Boggs.

In mid-April, 10 people boarded vans in Athens and travelled to Keysville.

THREE DAYS AND 70 NEW FRIENDS LATER…

None of them were there by chance. Each was carefully chosen for their respective abilities.

This charrette would involve three days spent on-site at Boggs, with alumni, faculty, and community members meeting for an exchange of ideas and information. “We pulled students from Education, and an African-American farmer who had worked with community agriculture programs,” says Lewis. A group of Boggs Academy alumni gathered onsite.

Their numbers swelled. When the UGA vans pulled onto the campus, nearly 70 people in total had assembled for the charrette’s opening event. They would discuss Boggs and hold discussions about rural America.

They took meals together and even shared a fish fry—all arranged by Thornton.

Boggs is remote—wooded and somewhat difficult to find, it is an island within a network of rural communities. That remoteness had been both a saving grace and a detriment. Its isolation might have been part of its protection. At one time, it afforded some protection from the outside, especially hostile groups like the Ku Klux Klan, who burned crosses more than once on the campus.

And post segregation, its remoteness also saved it; otherwise, it might have been razed for agricultural or corporate development if not for being an inconvenient 45 minutes from Augusta, the largest nearby city.

All of which fed neatly into the message from CED’s Cassity, who has been working with the Kettering Foundation in conjunction with their National Issues Forum. Cassity’s role with Kettering specifically concerns rural America, and how to prompt dynamic inquiry, “using creative and cultural tools,” he writes.

Lewis recalls, “Pratt asked, ‘What is good about rural Georgia; what is working against it? If you could make changes, what would you put in place?’”

Jones says those intensive days in Keysville allowed her to do research and spend face time with graduates and former faculty. She threw herself into interviewing them for first-person ethnographic accounts, knowing she was directly participating in the historic school’s metamorphosis.

Watching her interact with people, then get up and make presentations— Well!” Lewis laughs and shakes her head. “Anything that didn’t fall neatly into design, preservation, or agriculture, we gave to Stephanie.”

As an educator, Jones found it a thrilling and singular experience. “I was looking at the archives on campus, and looking at what was it like to be a student there?”

She interviewed former Boggs faculty, meeting one who lived next door to the Academy. As she steeped herself in the experience, Jones discovered that the people at Boggs had a prescient sense of destiny.

“They foreshadowed what happened to them. They wrote in one of their yearbooks that it was an incredible laboratory, ‘an infinite laboratory’.” Jones pauses, collecting her thoughts. “I pull this aside as an example of what happened there.”

The former maintenance supervisor at Boggs opened up to Jones during an interview, offering his thoughts about its future.

“He was candid with me; I asked him, ‘What do you think should happen?’ He said, ‘We need a place where kids can play. That is a part of education, too.’”

Then there was the question of the infrastructure of the remaining buildings. While most of the unused buildings were in ill repair, some could be rehabilitated. The fact that so much had survived in the 30 years since the school closed seemed remarkable. Jones noted that the large education room was in relatively good shape—but needed a new roof. The gym needed some work, but could be resurfaced—and also needed a roof and other repairs.

Jones took special note of the swimming pool, still in relatively good condition. To her, the pool was more than a nice amenity. It was emblematic of the surprising opportunity that Boggs had created for minorities in the segregated South. Having access to a pool was nearly impossible for most minorities, regardless of education or class.

“It was very, very rare to have a swimming pool for the African-American community,” she stresses. “Most African-American people didn’t learn how to swim because the pools were segregated.

“As an educator, the question was, ‘How can we remake this, how can we have courses built around it? Can we have basketball camps? Swimming lessons? Summer enrichment?’ All those are things are things every kid needs.”

But Jones knew her limits. She was an educator, neither a designer nor preservationist. “There were things I was unable to see, because my eye was not trained.”

Jones says what she knew from the first reading of the accidental group email had proven true: the experience was one not to miss.

“I am still making contact with people I met there…and maintaining relationships.” And, Jones had a central role to play in the Boggs charrette, one that she couldn’t have realized initially. Lewis found her to be the perfect go-to resource.

“We had all these issues swirling around, but there were only 10 of us,” says Lewis. “Stephanie took all this information, our discussions about the future of the campus, as an outreach center, etc., then she set it up. I thought this is why we needed a teacher—a good teacher.” The group was struck by Jones’s ability to distill the many issues and help explain them.

“I appreciate what the students do during this process — this charrette is a microcosm of history, gender, class.” – Ovita Thornton, Georgia Clients Council

Ovita Thornton – Boggs Academy board. Statewide director for nonprofit Georgia Clients Council

“THERE AS AN ADVOCATE OF EDUCATION…”

Jones was attracted to the Boggs project as one with staying power. “You sometimes do graduate level research and go into a community, and then you leave.”

In subsequent months, each graduate student wrote a chapter for a consolidated report. “The charrette is at a point that they have to make a decision,” says Lewis. “We will have a report and help them get started. But it is an ongoing relationship.”

Next steps will potentially involve a land management plan concerning the timber on the property. The people involved in the Boggs charrette will help with the next iteration, including long-term issues.

“The love you have for this place is going to make this place return.” – Pratt Cassity, Director of Public Service and Outreach, UGA College of Environment and Design

Dr. Pratt Cassity, College of Environment + Design, Director of Public Service and Outreach

BACK TO THE FUTURE

One of Boggs’s purposes is to be a living museum, and offer its space for ongoing programs. Towards that end, they have established a relationship with the Burke County school system, and a legacy mentoring program with Burke County students.

While only a few buildings are rehabilitated now, the condition of many of the facilities is still salvageable. There was once a drug store, canteen and dance hall. The dining hall remains, and there were four houses for faculty accommodations. Across the street is the church, still in use since 1926, and a manse. “Rehabilitation of the manse is wrapping up now,” says Cassity.

There were farmlands, agricultural buildings and fields. The students studied and worked in an on-site cannery, working dairy and laundry. The faculty on campus was international and multiracial, says Lewis.

Some of the alumni were the children of the famous. One student’s father was a musician with the Commodores. Another student was the son of a Gambian ambassador. Martin Luther King’s relatives are said to have attended Boggs.

The alumni shared endless coming-of-age stories with the UGA researchers.

Boggs students worked long hours, and were assigned “duty work” that had to be completed every day, says Cassity. Many returned to their families only at Christmas or during summer vacation. It was isolated, and the obligations were steep.

Yet, the alumni wept with happiness when the UGA team showed archival pictures from times when Boggs Academy still thrived. Jones took note of both the Boggs experience, and the CED’s approach.

“One thing I did not expect a charrette to do for me, was that it made me think about my teaching more,” observes Jones, sitting in the CED studio months later.

As her eyes scan the space, she comments about how the studio is configured to be shared. This contributes to consensual learning, she says.

“When we think about Google, or these interesting tech startups, this is what their offices look like. It’s collaboration. They don’t have private space. It’s like a studio. It’s a place where ideas are made.”

She grows animated as she connects people, resources, and materials in a studio-like environment, designed to be collaborative. “If there was some collaboration between the School of Design and College of Education…that would be powerful.”

Cassity observes that this type of “design thinking” is a current cover topic for Harvard Magazine. “It’s also the basis of some aspects of UGA’s THINC lab and the entrepreneurial certificate program.”

It will be the spring of 2016 when Jones completes her doctoral program, and will seek a tenure track position involving teacher education and literacy. If not that, well, then, Jones muses, and thinks of other possibilities.

For example, in this literacy teacher’s view, we could use more brick-and-mortar bookstores. “So I might open one of those!”

Meanwhile, educator Jones is still reflecting on the future of education in general, while processing how she can remain part of Boggs future.

As the future of Boggs unfolds, Jones says, “I still would love to be affiliated with this remarkable place…”

Boggs alumni see rows of seats in classrooms, neatly made beds in the dormitories and set tables in the dining halls. Instead of collapsed rooftops and the invasion of nesting insects, they see basketball games and assemblies held in the beloved gym, and savory meals of fried chicken and hot biscuits taken with their friends, after grace was gustily sung a capella.

BOGGS ACADEMY IN THEIR OWN WORDS:

The alumni described their years at Boggs as nearly idyllic. Boggs Academy graduates matriculated in college at the rate of 95 percent, according to a 1975 Ebony magazine article.

BARBARA PHILLIPS WILLIAMS, CLASS OF 1968

BARBARA PHILLIPS WILLIAMS, CLASS OF 1968

“It was the best thing that ever happened.” She went on to become the first college graduate in her family. “It gave me my start, opened up doors. I knew I wanted to be something.”

ALSIE DELORES (DEE DEE) PARKS, CLASS OF 1966

Parks excitedly recalls her first memories of September of 1961 when she was dropped off at Boggs. “I was a good girl—an A student,” she says. “We were one great family,” Parks notes. After 30 years in human resources at a major corporation, she counts Boggs as instrumental in her life success.

WINSTON COOK, CLASS OF 1962

Although he had resisted attending Boggs in the beginning, Cook recalls using his military leave to visit his alma mater. After leaving service, Cook entered college to study business and accounting. “When Boggs closed, I closed, because it hurt.”

GEORGENE SILLS MUSLIM, BOARD MEMBER

“People are saying in the community that Boggs will never come back, may not be the same. Don’t be discouraged…people from the University of Georgia are here upholding a dream. It keeps the life blood pumping.”

ALTON WEST, CLASS OF 1968

ALTON WEST, CLASS OF 1968

“Boggs represents what education needs today—that was family, that was a culture, an organization, a plethora of things…everything in my whole life was planned.” West describes learning oration, character, and manners. “We became each other’s parents.”

SABRINA LEWIS-BRADLEY, NEE SMITH, CLASS OF 1975

At age 12, Lewis-Bradley entered Boggs. She later studied art at the University of Georgia, graduating in 1977. “I was a scared 17-year-old when I went to the University of Georgia and graduated in three years…” “My father and mother went to Boggs. It has been, and always will, be a part of me.”

YVETTE HATCHER, CLASS OF 1983

YVETTE HATCHER, CLASS OF 1983

“The Boggs curriculum was ahead of the curve,” Hatcher says. “Boggs graduates are outspoken. They have a drive; it was instilled in us, the unspoken, but it was there. Going forward, I think, ‘What can I do for Boggs?’ Boggs means to me, a never-ending story but a beautiful ending.”

EMMA GRESHAM, CLASS OF 1940

Gresham reiterates that in her view, “This is holy ground.” She retired from teaching after 32 years and for 17 years worked as the mayor of Keysville, Ga. Today, she is president of DIVAS, a social club. She is also a member of DEALERS, which she helped found. The clubs fundraisers help provide high school graduates with a laptop computer.

RYAN THOMPSON, PRESIDENT, THE CENTRAL SAVANNAH RIVER AREA

“It has been a while since I’ve seen them [fellow alums], but once we get together, time is erased. There is a string between us, and all of it stems from Boggs.”

For Further Information about Boggs and other CED Charrettes:

tinyurl.com/BoggsCharretteFbook

www.ced.uga.edu/services_outreach/designcharrettes/

Seven years old and going to Boggs (1937) – YouTube www.youtube.com/watch?v=4tbZYD2mIQ4 To view a promotional film for the Presbyterian operated Boggs Academy (Keysville, Ga.), produced by the PCUSA Board of National Missions, 1937. [Motion Picture A104, Presbyterian Historical Society, Philadelphia, Pa.]

www.facebook.com/pages/Boggs-AcademyNational-Alumni-Association-Inc/ 141279679275735 The Facebook page for the Boggs Academy National Alumni Association, Inc.

For Further Reading about News Events Following the Supreme Court Ruling Brown V. Board of Education:

The Race Beat, by Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff