David Stanley

By: Cynthia Adams | Photos By: Nancy Evelyn

“Anything worth having is worth fighting for,” David Stanley says softly. His posture is perfect; he is self-possessed, mature, and, most of all, philosophical. “I want to go back to my Florida high school, middle school, and elementary school, and share: ‘I made it out of here.’”

Stanley’s message would be, he has not only survived the narrow straits of youth, but he has thrived.

If you didn’t know better, you might think Stanley is a younger version of writer Malcom Gladwell. Like Gladwell, he’s philosophical and deeply curious. In fact, Stanley seems far wiser, more contemplative, than his 28 years.

Presently, Stanley is a second year doctoral candidate in the counseling psychology program. His lead professor is Edward Delgado-Romero, a psychologist in the field of Multicultural Counseling Psychology.

“David is a mature person who feels a duty to give back to the community in many ways,” says Delgado-Romero. “He is extremely generous to his colleagues and always looking to affirm others.” He will graduate in 2020.

When Stanley is curious about the world around us, he opens his lens wider in order to better capture it. “Why do children and adults act the way they do?” he asks. The study of counseling psychology offers him a mechanism through which he can parse out an understanding. This is the discipline, as he views it, “that is wrapped up in everything.”

In his major discipline, Stanley finds a method and opportunity to translate his own experiences, and those of others. For some, like the young people back home in Jacksonville, Fla., it is more than an academic exercise: it can be life changing.

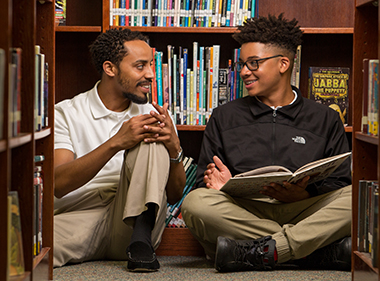

David Stanley in Clarke Middle School media center. Mentor of the year.

In January of this year, the College of Education graduate student was named Mentor of the Year at Clarke Middle School, Stanley joined the Clarke County Mentor Program in the fall of 2015. He is deeply interested in understanding how the parent-child relationship impacts achievement, especially for African-American youths. He also intends to continue tracking his young mentee, Kurali.

“My mentee makes my job easy,” says Stanley. “He has always been a bright student. However, he has grown so much personally, during our brief time together. I hope he feels like he has learned as much from me as I have learned from him!”

He likes working with youth, and feels an affinity for any young person, especially one who may have not been afforded all the opportunities that others have. Stanley has had to work beyond his own challenges; he relates to the struggle.

“I grew up in a single parent household, with my mother, Donna Stanley, an older sister, and a younger sister and brother. I’m the first to attend college.” Mentoring, Stanley says, began at home. That was where he first began modeling behaviors that he believed led to a productive and fulfilled life. His father, David Sr., was also engaged with him. But his first thought was always of his siblings.

“I wanted them (my sisters and brother) to see success and model that.”

Mentoring, Stanley explains, is a small piece of what he balances. He does a practicum at an on-campus mental health clinic, the Center for Counseling and Personal Evaluation, and at an off-campus inter-professional health center. He is a graduate assistant in recruitment at the Graduate School—all while pursuing doctoral studies. Here, too, he can model success to aspiring scholars.

Lisa Sperling, the senior director of recruitment and diversity initiatives, says, “David is one of my graduate assistants, and I am so proud of him!”

Born in San Diego, CA, Stanley was raised in Jacksonville, Fla. One of his friends and role models, Jamile Kitnurse, went to the University of Central Florida. Stanley applied there and the University of Southern Florida, but wound up attending Morehouse College in Atlanta, where he attended undergraduate school. It was due to his mother (who had insisted he fill out the applications to attend Morehouse) that he enrolled; he had already settled upon entering a local community college.

But there was more to succeeding at Morehouse than mastering academics. For Stanley, he had to first overcome his shyness. In order to succeed, he recognized “I had to get out of my shell.” In Jacksonville, keeping to himself had kept Stanley safe from trouble or harm. It was a self-protective effort and one which he philosophically calls “navigating the nuances of a challenging environment.”

It wasn’t unfounded. Stanley cites staggering statistics about his Jacksonville hometown. “106 juveniles were shot in less than two years, and 628 adults. That was a headline.” But once he left Jacksonville to pursue an education and career, Stanley had to discover a more open way to navigate adulthood.

Now, he wants to return to the Westside High School where he graduated in 2006 and share his story. He says he wants to walk the same halls, go to the same locker he once used, and let them know he has walked in their footsteps. He wants to serve as a positive model; something that he knows can make all the difference in a student’s life. “I made it out of here. You can make it out of here, too.”

But first, to “make it out,” Stanley had to learn how to be vulnerable. “If you know the landscape,” he explains, “you don’t have to worry as much.” By landscape, Stanley means the cultural landscape. Street smarts are an altogether different form of knowledge than books offer.

When he took an introductory psych course, he loved it. “One thing stood out,” he says. He was inspired by the work of one man: “Rene Descartes.”

Stanley found that when he read about Cartesian dualism, it helped him think more clearly about the duality of mind and body. It helped him decipher himself. Later, when he took an introductory philosophy course, he bumped into his old friend Descartes again.

Mentorship is an important aspect of Stanley’s personal mandate. As his mentor, Edward Delgado Romero writes, “David is a mature person who feels a duty to give back to the community in many ways.”

“My life kept intersecting with Descartes’ work,” he muses. Ultimately, Stanley found that “everything relates to why people behave the way they do. All the way to the books one decides to read!” He found a guidebook, as he explains it.

Visions of a Black Man, by Dr. Na’im Akbar

“One of my favorite books and one that helped me really gain insight as to what a man consists of was a book called Visions for Black Men, authored by Dr. Na’im Akbar, a psychologist that teaches courses in Black psychology. Actually, Dr. Akbar designed and taught the first Black psychology course in the history of Morehouse College, and eventually developed the first Black psychology program at the college. I learned of him through a talk that he gave while I was an undergraduate student.”

Actively Navigating the Future

Where might Stanley be 10 years from now, with a doctoral degree in hand? “I may be a professor, or in private practice,” he supposes. “Maybe partner with a non-profit organization. Or, maybe, I’ll be a motivational speaker.” With his positive demeanor and confidence, this is entirely believable. He personally understands the value of motivation. This he found very close to home.

The power of one, he supposes, can be enough to sustain a dream. Stanley’s aunt, Daphne Farrell, has been a longtime inspiration. His aunt modeled what success looked like. “She is a true beauty,” he says. Farrell went to school and became successful. “She showed it was possible,” he says.

Now, having survived youth—one fraught with minefields for so many of his contemporaries—Stanley knows the road to fulfillment and success is open to him. He is ready to show that to others and help uplift them, too.

“It is not enough to have a good mind; the main thing is to use it well,” Descartes said.

Stanley emails later: “My intended research focus is to better understand the cultural influences that contribute to the resilience of Black male undergraduate and graduate students, specifically around their career choice.”

He’s ready to be an influencer in his own right. Stanley, a dreamer and doer, is on his way.

His professor adds that he, too, is proud of Stanley. Delgado-Romero says, “He was drawn to a doctoral program in counseling psychology because of our values in diversity and strength-based views. He embodies those ideals.”