Jessie Johnson & Matthew Schneider

Leaving Good Will in Their Wake: Meet Leave No Trace’s Jessie Johnson and Matthew Schneider

By: Cindy Adams | Photos By: Nancy Evelyn

On a winter’s afternoon, UGA alumni Jessie Johnson and Matthew Schneider had a brief opportunity for a warm respite, ducking into a coffee shop while in North Carolina for a weekend training event. Johnson, 37, received an MA in Sociology (2005). Schneider, 39, earned a Ph.D. in Philosophy (2010).

They found a sunny table in downtown Greensboro’s Green Bean, taking advantage of the warmth of hot drinks and a makeshift office offering Wi-Fi. This and every day for the past two years, the couple adapt to available resources and continue their work as educators on the go.

Johnson and Schneider were on day 524 of what will be three years as traveling trainers with the Colorado-based nonprofit, Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics. They know the date well, as they have kept careful logs, mindful of the passing days as they crisscross the most wild and beautiful spaces in the nation.

With every passing day, their enthusiasm for the life of outdoor trainers only grew.

Wiggle Room: No Shirt, No Shoes, No Problem!

With their Leave No Trace Subaru and trailer securely parked nearby, the duo of educators answered emails and prepared for a weekend training session for Carolina Outdoor Adventure Leadership Summit, a training program hosted by the University of North Carolina-Wilmington.

The duo showed the benefit of their healthy lifestyle. Both are well-toned, ruddy and exuded good health. Although in their late 30s, they appeared younger. Wearing athletic wear, the couple had earbuds in place as they scrutinized their laptops, surrounded by backpacks.

A spot in a Wi-fi connected coffee shop where they could respond to emails was as close to an afternoon at the office as they would approximate, given their home is a tent in the great outdoors.

Johnson and Schneider have no permanent address, no “home” per se, but live on the road and camp in public campgrounds or sometimes on private land. They are one of four pairs of Leave No Trace professional trainers who travel the nation promoting the Leave No Trace precepts and advocating for best outdoor practices. In the course of 11 months annually spent on the road, their work demands presenting to a variety of groups, leading communications and training workshops while crisscrossing the nation.

As of the beginning of 2019, the couple has logged 65,000 miles and spent the past two years camping and promoting ideas that educate and conserve natural resources. “Working closely with all federal land management agencies, along with state and municipal agencies,” says Johnson. “We’ve personally worked with the Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Forest Service, US Fish and Wildlife, National Parks, multiple cities’ park and rec, and lots of state parks.”

They insist it is well worth it. Their ideas about advocacy and adopting a simpler way of life have validated their chosen lifestyle, especially given the public’s frequent lack of outdoor education.

Camping 200 Nights in One Year…

After leading the training program in N.C., Johnson and Schneider were figuring out their agenda.

Where the intrepid couple would go next depended largely upon the federal government’s shutdown, which had continued for nearly a record-setting month. In the meantime, federal parks were closed, and minus park staff and employees, it would be difficult for Johnson and Schneider to go forward with their usual planning and programs.

And then, that very afternoon as they were working through emails, the government shutdown ended.

Afterward, Johnson and Schneider spoke about the shutdown’s significance. Parks are already understaffed, as they explained; shutdowns impact education as well as many other, unseen, yet necessary operations.

In their travels to national parks, they witness the impact of funding struggles firsthand.

More often than not, they are staying in public parks.

“We camped about 60 nights a year before the job,” says Johnson. “Last year, we camped 200 nights.”

A Tiny House “Seems Like Such a Cramped Space.”

Given the extremes of winter weather, with record temperatures and rainfall, full time camping as a lifestyle seemed especially challenging. (Prior to their current jobs, the couple had conventional jobs and owned a home.)

For the majority of the time, they pitched a tent. As in, no-frills tent camping. More nights than not, the duo sleep beneath a canopy of stars.

Often, too, the educators truly rough it, without even a camping space available.

That means they have to somehow find a place to pitch camp.

“Dry camping—meaning, camping on land, but with no water or facilities.” Schneider elaborates: “Pasture, field, or desert.” Which, of course, also means figuring out basic ablutions, cooking and sleeping.

For some, that would be too much to ask. For Johnson and Schneider, it is business as usual.

How has loss of creature comforts affected their daily lives?

How, too, do Johnson and Schneider contend with being on the road all the time?

Apparently, they found compensations. They wisely invested in a Y membership which has proved very useful for both showering when dry camping, and also for maintaining swimming and general fitness when weather is extreme.

As for fitness, both are avid climbers, cyclists and runners, and travel with mountain bikes.

Last year, Johnson and Schneider got luckier concerning creature comforts, although some of their more dramatic Facebook posts show them having to thaw frozen liquids and foods over a camp fire.

“We have had a lot more campgrounds this (past) year,” Johnson adds.

In between work gigs, they will occasionally stop for a respite at a friend’s house.

“We’re anchored to our car and trailer,” Schneider admits. “That’s where all our stuff lives. But when we go stay at a hotel or Airbnb…we’re like, ‘did you bring this in? Where is it?’”

Strangely enough, the camping life has left them only itching for more of the great outdoors.

Last year, Johnson and Schneider experienced the tiny house phenomenon for a week’s stay while giving a program in Portland, Oregon. Given their lack of materialism, it might seem the pair would dream one day of pitching up permanently in a tiny house?

But surprise—Johnson and Schneider say that 150 square feet just wasn’t their cuppa tea.

The pair agreed the Oregon tiny house “seems like such a cramped space.” Schneider “found it confining.” He pauses. “Whereas, like when you’re camping, you’re outside.”

The sky for a ceiling still pleased them far more than a conventional house.

“Oh, yeah,” confirms Schneider.

Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics

The nonprofit Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics, headquartered in Boulder, Colorado, is a national organization that seeks to teach and inspire outdoor goers to adopt simple practices to protect the environment.

Jessie Schneider says Leave No Trace “came to fruition basically when park service, forest service and other land management agencies had the same issue as now. There’s never enough staff to help people know what to do when either camping, or hiking or paddling or picnicking to make good decisions to sustain these places, whose use has gone up and up and up.”

As various nongovernmental entities focused upon education, research and curriculum, they considered how to best get information pushed out to the public, says Schneider. Partnerships with for-profits emerged.

“We have a lot of partners,” she adds. “Automaker Subaru is one, and they supply the LNT educator teams with vehicles.”

“So, we don’t have to walk from place to place,” says a joking Matthew Schneider. REI, the outdoor outfitter chain, is another high-profile partner.

The Vista is Either Through a Windshield or a Tent Flap

Prior to taking the training job, the couple biked, ran, enjoyed marathons, and camped weekends as often as possible. Johnson’s past roles seem tailored made for her present life. She has been a children’s librarian, outdoor educator, and has volunteered as a Girl Scout troop leader and for sea turtle patrol.

She also enjoyed backpacking, hiking, and camping, writing that “Matt would pick me up at work every Friday, bikes and burritos ready to go.”

Hayley Cox, development officer for UGA’s Graduate School, was a colleague of Johnson’s in 2010-11.

“I worked with Jessie at the Oconee County Library in Watkinsville, Ga.,” says Cox. “Jessie is warm and makes people feel immediately comfortable. As a children’s librarian, kids and parents alike adored her, and as a colleague, she was always aware of opportunities to support the rest of her team, pitching in with any task, regardless of her own workload.”

Schneider, an Eagle Scout, has been a camp counselor, outdoor trip leader, philosophy professor and a challenge course leader. (As he says, in that order.) He writes in his bio that he has “paddled, pedaled, hiked, climbed, surfed and caved on three continents and in 11 countries and 32 states over

the years.”

How did they get their Subaru/Leave no Trace traveling trainer jobs?

“Because we applied,” deadpanned Johnson, grinning widely.

After getting the gig in 2017, the adventurers sold their home in coastal Georgia, gave away everything except what would fit into a small U-Haul, stored it, and became official Subaru/Leave No Trace Traveling Trainers—driving a Subaru, naturally.

It all sounds very much like the Great Escape—the fantasy of every 9-5 working stiff, walking away from the corrupting influences of mortgage, materialism and stifling tradition.

Not really, they say.

“We’re not trying to escape anything,” insists Johnson. (They aren’t even anti possessions. Like most of us, they have a weakness for non-essentials, even admitting to a fondness for stuffed animals.)

“We minimize our belongings, getting to be outside.”

It has been a worthy, even exhilarating trade off, they say.

The couple were inspired by their friends and Internet examples knowing others who headed into the woods long before they followed suit. Their plan was far more planned.

“It’s becoming a more popular way of living. We would follow people online,” Johnson says. “Everyone’s story begins this same way: ‘Going to work 9-5. Then, one day, sold our house.’”

Most people who learn about their odyssey, the couple say, “are perplexed but intrigued. Some think it’s neat but don’t understand.”

Admittedly, even their families were perplexed. After all, prior to their nomadic work life, they were living what appeared to be an idyllic life on St. Simons Island. By many peoples’ standards, Johnson and Schneider were already in paradise. But it was a life more conventional than their present lives, then rooted in one place. Spending the majority of their workdays outdoors with an ever changing backdrop was precisely what they wanted.

“We opted out of routine, but not of obligation,” stresses Johnson.

With 2018’s obligations largely wrapped up, they spent last December off the road. “By the end of the month, we were antsy” says Schneider.

A month of looking at sheetrock ceilings had them longing to sleep beneath the Milky Way. The road beckoned. They anticipated a calendar of endless adventures.

Some Leave No Trace events are memorable, standouts even by the cinema-ready standards of their designated camping locales. “A big event at Yosemite every year,” recalls Schneider, “evolved into a four to five day event.” Also, they point out, Yosemite lives up to its reputation for natural beauty.

Leave No Trace sponsors a backpack tag identifying registered Appalachian Trail Thru-Hikers. Registered hikers receive year-specific hang tags like the one shown at left.

“Completing the entire 2,192 miles of the Appalachian National Scenic Trail (A.T.) in one trip is a mammoth undertaking, usually spanning 5 to 7 months,” notes the ATC website. Hikers can register starting dates and locations, ensuring safer and less complicated hiking.

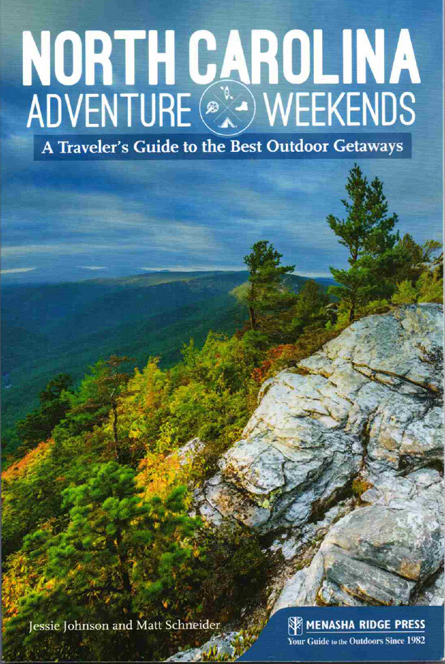

In 2017, Johnson and Schneider published their first book. It was written prior to beginning their job as traveling trainers. North Carolina Adventure Weekends: A Traveler’s Guide to the Best Outdoor Getaways was released under the imprint of Menasha Ridge Press.

The 208-page outdoor guidebook provides suggestions for their 12 best weekend adventure destinations, rating hiking cycling, climbing and paddling according to difficulty. It provides lodging options, as well as suggestions for food and drink.

Their future may hold more writing, they suggest, as the publisher has requested additional books.

A smiling Johnson admitted she, too, is both curious and excited about their next chosen adventure.

For More Information:

Johnson and Schneider appear in a Subaru commercial shot early this year in Burbank, Ca. To view it see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=10QyLxU_7AY&feature=youtu.be&fbclid=IwAR3tSEM54Dkr0BPkQdVO5G8s7SgDeyoBWaEnPu3Z0XTPypI081aRduDgNCo

Visit the Leave No Trace website at: https://lnt.org/

To join the Leave No Trace movement: https://Int.org/learn-about-membership

To visit the Subaru/Leave No Trace Traveling Trainer’s website: https://lnt.org/about/traveling-teams

To follow Johnson and Schneider on Facebook and Instagram, visit: @epicweekendadventures

To order North Carolina Adventure Weekends: A Traveler’s Guide to the Best Outdoor Getaways https://www.amazon.com/dp/B075V4N5DX/ref=dp-kindle-redirect?_encoding=UTF8&btkr=1

Q. Weather during this period has been extreme. How do you cope when the outdoor temps are so variable? And how many times have you simply had to seek indoor accommodations when things were simply too drastic? (And what actually constitutes too drastic by your measure?)

A. Because we generally travel with the seasons, we haven’t had to deal with too much extreme weather! There have only been a handful of times that we’ve “jumped ship” and had to leave our campsite—or decided against camping—because of the weather. Of course, Mother Nature is unpredictable. We’ve had to pack up our tent in a windstorm that was so intense that I had to sprawl out inside of the tent while Matt took it down to keep the wind from whipping it across the Arizona desert. We also have a hotel stipend to use in inclement weather or when there’s no camping available. Also, if a host requests a program and knows that the weather is likely to be bad while we’re there, he/she will offer indoor lodging of some sort—a bunkhouse, state park cabin, guest room, etc.

Our general definition of too drastic is any weather that’s dangerous to us and/or our gear. Again, thinking about those windstorms, lightning, rain that our tent can’t keep out, etc. We haven’t had to deal with much extreme cold, snow or ice, luckily, because of how our schedule is set up.

Q. On the flip side, I kept thinking of practicalities of nomadic life. How did you figure out the necessary essentials? Of course, I know you were no strangers to camping and backpacking, but living full time on the road is something else again. What happens to basic possessions, such as books, maps, souvenirs? How do you discipline yourselves? What learning curve was there to adapt to a nomadic, minimalist lifestyle?

A. Necessary essentials haven’t been too hard to come by. One, because, while people picture us tromping through the rough wilds of North America, we’re often working in what we call “front country” areas. These areas are places people visit for the day where they might have a picnic, go for a short hike, splash around in a lake’s swimming area or take pictures at a beautiful overlook. These areas aren’t too far from civilization in the form of grocery stores, coffee shops, Target, etc. So, we’re able to stock up on basic supplies frequently. Amazon lockers have been helpful, too. We can place an order and pick it up at an Amazon locker, which are often at gas stations, grocery stores, etc.

Two, we’ve also redefined what “necessary essentials” mean to us. Part of the appeal of taking on a job with this lifestyle was leading a more minimal life; something we were already working on while living in a house. Of course, we got a bigger car and a gear trailer when we started our second year on the road, so we have to admit that our list of necessary essentials has expanded somewhat.

Before taking this job, we went through everything in our house—we literally put our hands on every item we owned—and decided what would be worth moving and storing, and what could be replaced. We took a small U-Haul of what we decided to keep and are storing items with our very gracious family. Now that we’re on the road, we are pretty ruthless when it comes to what we keep with us. We don’t buy much and occasionally will send things we want to keep back to our family.

The biggest learning curve was to learn to go with the flow and not get too riled up by mishaps, especially when it comes to things breaking. Because something is ALWAYS breaking and it’s never going to be convenient to fix—so you might as well just laugh it off.

Q. Inasmuch as I gather you were both keen to be very well-educated adventurers, and that you both share an important vision and mission as your work, what else do you see in your futures? Will you contemplate starting your own educational nonprofit given you are both especially qualified and have advanced degrees? Or do you intend to live on the road as long as possible and remain trainers given your joy and wanderlust? What does that future look like from your perspective?

A. Short answer—we don’t know. We are currently putting energy into making our last year and a half on the road as Traveling Trainers as successful and fulfilling as possible. Right now, an ideal life for us would allow for lots of travel, but also a home base to return to from time to time. We might consider writing more travel books or doing consulting work. Or, maybe, by spring 2020, we’ll be ready to get back to “normal” life.

Q. And how has this lifestyle changed you? Has this work made you grow more jaded about our culture, or less?

A. We’ve been able to redefine the definition of “home.” Even when we’re moving, on average, every three days or so, wherever we set up camp is home and it always feels good to return there—wherever “there” is—after working all day. We’ve both become more flexible in terms of our lifestyle because, well, we have to be, and are more sensitive to each other’s needs/desires/pet peeves. When you’re living, working and traveling together almost 24-7, you realize how much of an effect, positive or negative, you have on your partner.

We were both fairly optimistic people before taking this job and, while we see a lot of harsh realities in terms of the recreational impacts we have on the environment, we’ve also met hundreds of land managers, volunteers and people who are just so incredibly passionate about protecting our awesome public lands. They’re problem solvers and are always looking for the best way to help people make good decisions when they’re outside, even with all the challenges they face, like slim budgets and too few staff. So, while we can’t say we were jaded before, we’re definitely not more jaded now!

- Pizza on the California coast. Image: Jessie Johnson, copyright: Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics

- Mojave desert late winter. Image: Matt Schneider, copyright: Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics

- Shenandoah National Park. copyright: Matt Schneider

Photos Courtesy of Jessie Johnson, Matt Schneider, Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics

Q. How difficult is reentry when you are off the road? You mentioned becoming antsy when you were visiting folks over the holidays. What is it you most miss when you are more confined?

A. When we take a little bit of time off the road over the holidays, it’s not too difficult to “reenter.” It’s such an amazing experience to get to spend that time with family and friends, and we usually have a list of logistics that we need to take care of while we have a home base for a bit. So, we have no real complaints about that, especially because our family and friends are so gracious and generous to open up their homes to us. We do miss life outside (although, maybe not so much in December)—you miss so much when you’re sleeping inside. Incredibly starry nights, animal noises, fresh air, new places, the simple camping lifestyle. Plus, we’re always aware of being in someone else’s space and, like we mentioned, it’s nice to return “home” to a campsite because that’s our space, our home.

Q. Also, reading online concerning the mission of LNT, I keep wondering what to make of the fact that record numbers of people are going to public parks, but clearly, seem ignorant of the impact. That parks are challenged by simply coping with the (staggering!) impact of human waste—of every kind—is dumbfounding. This alone seems to be generating an enormous amount of problems. What is the disconnect? Do you find people have simply failed to register that it is devastating, environmentally and as a matter of civility, to not deal with their own wastes?

A. In the past two years, we’ve had conversations with thousands of people who either work in the outdoors or who enjoy spending time outside. We’ve learned that impacts usually—not always, but usually—occur not because people are trying to be malicious, but because they don’t have the knowledge or skills to make a better decision.

As a society, we’re very much used to having access to trash cans and toilets. Sometimes people will say that Leave No Trace skills are common sense. But if you’ve always had access to a toilet and most of your outdoor adventures are day trips, you very well might not intuitively know that the best way to take care of human waste in most places is to dig a six to eight-inch cat hole, 200 feet away from trails, water, campsites, or parking lots. That’s a skill! In terms of trash, if there’s always been a trash can in your favorite picnic area, you might not bring a trash bag. In that case, you might not have an easy way to take your trash home with you and, while you don’t want to leave it, you aren’t necessarily going to throw your watermelon rinds in the trunk of your car.

A lot of us are trying to do the right thing outside, which is why we end up with a lot of food trash left behind. People look at apple cores and orange peels and think, “Hey, this is biodegradable—I’ll leave it here so it can break down” But they don’t think about how long those things take to break down and, in the meantime, they attract animals to trails, roads and people.

It’s easy to get overwhelmed quickly in the outdoors, too, and we don’t make the best decisions when we’re cold, wet, hungry, thirsty or feeling lost, and while we would usually never forget a bag of trash at our lunch spot, if it starts raining and we don’t have any rain gear, we’re very likely to go into “survival mode” and forget about things like packing out our trash. That’s why the first principle of Leave No Trace is to “Plan Ahead and Prepare.”

Education really does help with a lot of those issues. Most people want to do things the right way and part of our mission is to get them the information they need before they go outside so that they know how to do the right thing. It’s also imperative that people understand the reasons behind Leave No Trace recommendations.

Why do we recommend digging those cat holes six to eight inches? That’s where there’s the most microbial action in the soil and that helps break down waste. If you dig too deep, you hit mineral soil where it won’t decompose as well. Too shallow and you risk exposing your waste to people or to insects who might land on your sandwich! We need to be internally motivated to do the right thing and to develop our own outdoor ethic.

“The first principle of Leave No Trace is to ‘Plan Ahead and Prepare.’ It’s easy to get overwhelmed in the outdoors – we don’t make the best decisions when we’re cold, wet, hungry, thirsty, or feeling lost.” -Matthew Schneider