Benjamin Leiva

By: Cynthia Adams | Photos By: Nancy Evelyn

Benjamin Leiva was the tenth and final speaker at 3MT this past April. When he took the stage in Cine theater in downtown Athens, he noticed that the venue was filled to capacity with 127 keen observers who had scored a ticket.

In recent years, 3MT has grown into a rigorous communication exercise.

During its history at UGA, the event has become increasingly competitive and slots to present are sought after—and so are seats for spectators.

“We had to turn people away, unfortunately,” says Meredith Welch-Divine, who directs the annual event.

Given the finalists were preselected from a field of 70 graduate student hopefuls, there was no question that it didn’t help presenters’ nerves to consider that fact.

The competition rules are strict: only one static slide allowed the presenters, and merely three minutes to summarize their research. Another 3MT requirement is that the presentations given by the 10 finalists must be designed for a general audience. The audience members, in fact, get to choose one of the three awards given: The People’s Choice Award.

Leiva was dead last on the program; the evening was growing late. It wasn’t as if being tenth in order meant he would start 27 minutes after the competition either. Despite each speaker having only three minutes to present, a master of ceremonies gave introductions and bantered before each.

Leiva, who has taught courses in sustainability, economics and ecology, will earn his doctorate in agricultural and applied economics in 2019. He is well accustomed to an audience.

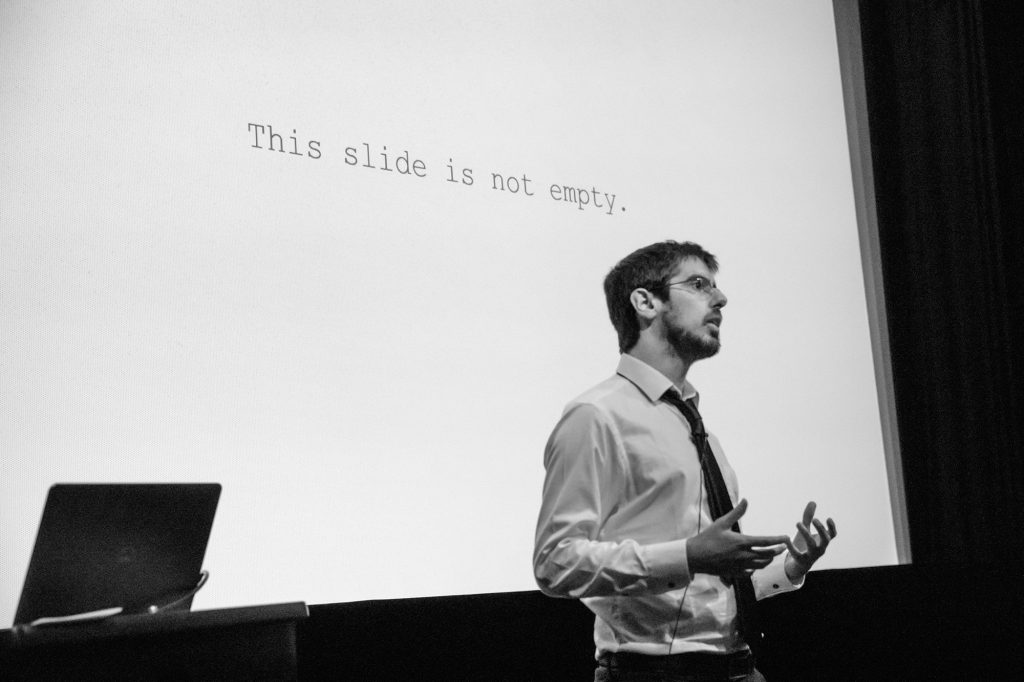

When he confidently took the stage to speak on “Economics and Energy: Getting More Light Than Heat” what appeared to be a possible error filled the onstage screen.

A blank screen.

Audience members glanced at one another in sympathy and confusion. There were sympathetic murmurs. Was the final presenter having A/V problems?

Not at all. In fact, things were going exactly as planned.

Benjamin Leiva was teaching his audience about the power of negative space.

“This slide is not empty,” he said, as members of the audience straightened in their seats, now watching intently.

“Actually, it is teeming with energy in the form of photons that are reaching our eyes. In the same imperceptible way, energy in the form of glucose allows us to breathe and live, in the form of electricity our computers to work, and in the form of oil our cars to run. Quite literally, energy makes the world go ‘round. In the natural world it allows galaxies to rotate and the ATP synthase to work, and in economic systems energy enables the production of every single good we consume.”

Three minutes later, Leiva had caused his audience to think about economics and energy in a very novel way.

Later, he smiled widely as he remembered the presentation and the attention given his deliberately blank screen. “I was thinking a long time about what I should put there,” he explained over coffee, as fellow students filled a Broad Street Starbucks.

Leiva had initially brainstormed the slide with his girlfriend, Maria Fernanda Terraza.

“She had the idea of different cells/systems dissipating, moving energy around…then I thought, what if I kept it blank?”

Leiva decided a completely blank slide made sense. All white with an absence of graphics would symbolically convey what concerned him most: energy.

“White is (the presence of) all the colors,” he explains. “Light is the primary way that we receive energy from the sun. I talk about something that people can’t see, can’t touch, cannot smell—that challenge of relating something to someone that hasn’t been related to it.”

He pauses. Most people understand they need electricity for various functions, like charging cell phones, he says. But they don’t consider that when they eat, they are doing so in order to gain energy.

Leiva now had the concept for a single slide visual. Now, he only had to hone his speech down. Public speaking was familiar to him, as he had trained since an adolescent growing up in Chile. But 3MT’s time limitations were another matter.

“I did debate when I was younger, and I had experience with public speaking in Chile from middle school. You had to present, not only for your classmates, but others in the school were invited. They trained you to be up there on a stage, since age 12. You had to do this once a year, which I feel was big training.” But, Leiva adds, “I had never had to say every word with that specific timing.”

A Student of the Americas

Leiva’s family left Chile during the 1970s when Nicaragua was in the midst of a Civil War. Leiva’s father accepted a position with the United Nations Development Program, or UNDP, in Nicaragua. Benjamin was born in Nicaragua during that time.

“My dad went to help the government control inflation, working for the UNDP.”

Leiva later returned with his family to Chile. Years later, at the Universidad de Chile, he began thinking about economics in a nonconventional way.

Eventually, Leiva had an insightful breakthrough. It was an “aha” moment.

“It was in 2013-14, during the summer in Chile, in December or January. I was reading this ecology book,” he explains. “And I got to the food chain…the food pyramid. (I read) how energy flows through trophic structures. All living systems are arranged according to energy, almost everywhere.”

This caused him to reflect. Here was something he felt long missing throughout his undergraduate studies. Previously, environmentalists and scientists have looked at ecosystems. But here, in the contemplation of energy, Leiva found a missing piece of the economics puzzle.

His work addresses this missing element.

Leiva considers how raw materials are manipulated and modified into final goods that are convenient to us.

“Energy comes in (to play) very clearly, because the only way matter can be rearranged is with energy transfers.” People, horses, machines—all are systems that transfer energy, as he explains.

After the Epiphany: Translating an Idea

After having that moment of discovery, Leiva looked for physicists to discuss his ideas. One of his best friend’s brother was in his last year of physics studies. Initially, the economist struggled to communicate with the physicist, a problem exacerbated by a language gap.

“It was difficult because the languages were so different. For several weeks it was impossible for us to understand each other,” says Leiva.

He was patient, and strongly motivated to understand the relation between economics and energy. Over time he had more than 10 conversations with the physicist.

Leiva explains the ways in which the dialogue was useful. “The physicist was interested in the idea that this underlies my understanding; why complex systems exist from an abstract perception.”

He illustrates this further. “When you think of a car, it’s metal and plastics that were, before, underground, or (in the form of) crude oil. We put these other elements together and built these functional units, for example, as a car, a cell phone, a cup of coffee that we can enjoy. And what we find are prime movers take energy goods, and their energy content, and transfer the energy.”

Leiva points to my notes on a notepad. “When you write an article, you are doing this right now; atoms are transformed and arranged in a very specific form that someone else can decode into knowledge.”

Then, Leiva holds up a coffee cup. “This, too, was transformed so that I can enjoy it.”

He is both excited and dismayed by his insight.

“What is frustrating is that economic theory has not considered energy seriously. A 200-year-old discipline that has yet to understand what is its object to study? Because production is one of the most fundamental issues we deal with…it’s so obvious that it’s almost boring to talk about!”

Leiva argues that economists should not have unassailable axioms that are not up for debate. He argues that we should not have “religious relationships” with our ideas.

As he nears the completion of his doctoral research, Leiva is convinced energy plays a fundamental role in production and, therefore, underpins each aspect of economics, not merely one.

“Force times distance equals work; work is energy. When I learned that work is measured energy, I connected physics with economics…again, because of the transfer of energy.”

His ultimate takeaway from his work? “My take is that the most evident error in economic theory is the absolute neglect of the role played by energy in production.”

He is at the core an intellectual, one who believes in the absolute value of knowledge and rejecting what he calls “today’s incentive scheme in academia known as ‘publish or perish.’”

Leiva points to no less than one of Western civilizations’ renowned scientists and philosophers, saying, “Aristotle argued that, the most valuable form of knowledge is entirely useless.”

His brows knit, as the economist discusses his underpinning desire, which is even more straightforward: to make the world better.

In the final analysis, the classic scholar is motivated by the ecological crisis of our time, and views sustainability as underpinning all other challenges.