Abha Rai

By: Cynthia Adams | Photos By: Nancy Evelyn

Abha Rai’s social activism was born in Bangalore, India, which has a population of 10 million and is India’s third most populous city. Her interest was sparked by her mother’s work with community-based organizations there.

During important formative years, she spent time trailing her mother, becoming a careful observer. According to the Times of India, at least a third of all violence against women in Bangalore is due to domestic violence. In short, an alarming number of women are unsafe in their own homes.

Their shared experiences seeded Rai’s later interest in gender disparities, patriarchy and domestic violence —becoming the focus of her doctoral research at UGA’s School of Social Work.

A Sobering “World of Reality” Revealed

Now age 30, Rai is a self-described “goofy nerd” with a sense of humor. As a youth, she grew up as an only child and became an earnest student. She was more inclined to spend time with adults than rather the usual teenage pastimes.

As soon as she was old enough, Rai volunteered alongside her mother, who worked in the field with social agencies. Rai was provided a wide lens trained upon Indian culture, and observed the mores of people from all social strata in a country with deeply ingrained traditions.

As she matured and learned of social issues, Rai’s empathy and interest also grew. She kept a listening ear, attuned to the many stories of patriarchy and worse, and learned about the taboo topic of domestic violence.

There were overheard whispers from those hired to do cooking and cleaning within her extended circle.

“I grew up hearing all that,” she says quietly, adding she also learned much through neighbors, and certain relatives. Although her own household was peaceful and loving, Rai soon understood that homes were not necessarily safe havens for the women who lived there.

“I heard stories of people being hit,” Rai says somberly. “Growing up, I had not seen any domestic violence, although if you look at my extended family, there are instances of patriarchy and gender stereotypes as is in many other South Asian households.”

Her mother, Seema Rai, had revealed a “world of reality” and it was one that Rai could not, nor would, forget. As for stereotypes, domestic violence doesn’t conform. It isn’t confined to class nor wealth.

“Domestic violence doesn’t distinguish based upon your socioeconomic status.”

India remains a largely traditional place with patriarchal social views still in place, even as women ascend and assume roles of seeming equality. There remains an imbalance of power between men and women. According to the NGO Enfold Trust, “many women are doing well in the corporate sector, but wouldn’t report domestic violence fearing social norms.”

As Rai became a young adult, the stories, whispers, and muttered truths haunted her and grew louder.

“I think I always wanted to be a social worker,” she says. “I wanted to be a social worker because of my mother; and, I cannot think of a better person than my mother to motivate me.”

After completing a bachelors in Academic Law, Rai accepted a position in a consulting firm that worked with private companies and community-based organizations. While there, she helped create community-based programs “in alignment with the vision/mission of the funding company.” But largely, Rai was still following in her mother’s impressive footsteps.

The earnest young woman from Bangalore entered graduate studies in Mumbai, India.

She wanted to expose widespread abuses beyond domestic violence. Rai says, “I worked in the field a lot, later writing my master’s thesis on sex trafficking and sex workers. Seeing how people disrespected sex workers was disturbing on so many levels.”

The Forum for Women’s Rights reports that society’s outlook is still unchanged and doesn’t support women adequately. As media reports across India reveal, social views remain stubbornly patriarchal. Even an educated, professional woman may hesitate to report domestic violence and might not find support.

Rai is her mother’s child, she explains; her mother’s influences are indelibly imprinted. Their relationship was further intensified by Seema Rai’s long-term battle with kidney disease. By the age of 17, Rai was accompanying her on frequent hospital treatments.

Meanwhile, she met her future husband, Tarun Aggarwal, through a cousin. When the couple became engaged, it was to her mother’s great delight. Rai describes her mother as an incurable romantic, one who eagerly planned each detail of her daughter’s wedding.

And then Rai lost her mother to kidney disease in May, 2010.

In December after her mother’s death, Rai married Aggarwal, carefully adhering to her mother’s wedding suggestions.

She also recognized and appreciated that her fiancé had assisted her not only through her final undergraduate exams “but also my grief.” Aggarwal was a supportive, sympathetic partner, just as Rai hoped. Her in-laws were also, and a newly extended family fully supported Rai’s academic interests.

Separations were frequent for the newlyweds, because Aggarwal was in India’s Merchant Navy. Rai independently moved forward. “I went on to get my masters while figuring out life. Then, my husband came to the U.S. to study.”

In 2014, Aggarwal came to Indiana, where he earned an MBA at Purdue. Rai rejoined him a few months later. He is now a senior operations manager for Amazon in Dallas, Tx. Separations are an ongoing necessity. She pauses. “We’re apart most of the time because of my school and his work,” she adds, knitting her brows.

But, Rai stresses, “he understands and learns all about my research.”

Prior to her entering UGA, the couple were in Chattanooga, Tenn. While there, she met a circle of South Asian friends and became friends with her fellow expatriates.

Rai took particular notice of a lonely South Asian woman at the local gym. “She had no friends. She couldn’t communicate.” Their native language differed and the woman did not speak English, the lingua franca.

When Rai attempted befriending her, ultimately communicating via sign language, her radar was on alert. She further noticed the woman had no cell phone, nor could she drive. “She wasn’t being helped to acculturate. I am sure this was challenging for her.”

Armed with past experience, Rai recognized the social isolation engulfing her lonely friend for what it was. This, too, was an indication of domestic abuse. “There was some domestic violence even there,” she observed. “I began studying the special challenges these [immigrating] women faced. It was the turning point.”

Rai wanted to develop interventions specifically to help immigrant women who are coping with domestic violence issues.

The differences for the victims of abuse in such cases are twofold: not speaking the language, as Rai explains, and not being able to work.

“Right now, women can work on an H-4 visa but they are dependent on their husbands for this visa. The ‘main visa’ holder, most commonly the husband, can file for an H-4 only after he meets certain immigration criteria. But, it is so demoralizing for women who are educated and used to working who cannot.”

Ultimately, these factors may seed the perfect storm of social problems for immigrating couples. The lack of social interaction, communication struggles, and lack of purpose culminate in cyclical frustrations at the very least. At its worse, the frustrations spiral into violence.

“Right now, women can work on an H-4 visa but they are dependent on their husbands for this visa. The ‘main visa’ holder, most commonly the husband, can file for an H-4 only after he meets certain immigration criteria. But, it is so demoralizing for women who are educated and used to working who cannot.”

“Stop the Violence, End the Silence”

Before visiting Athens in 2016, Rai was made an offer by UGA but needed to be certain that this was a diverse campus, one where she would feel at home. She walked the campus and felt an immediate sense of ease. When Rai toured the School of Social Work, it sealed the deal for her.

“UGA felt right for me. I feel that Georgia is so welcoming,” she says. “On my first day, the first meeting I had, I found that.”

The culture and diversity at UGA were as she hoped.

“Seeing people of all color was so comforting to me. I didn’t have to feel so different. And we have a diverse faculty in the School of Social Work, not of a single race. My advisor, Y. Joon Choi, is originally from South Korea. That is why I like Georgia,”

“I love it here,” Rai smiles widely. “Even at the School of Social Work, our Dean Anna Scheyett and all other faculty members are amazing. They have always supported me and I know they always have my back!”

Last December, Rai received the Tarakanath Das Foundation Graduate Student Grant. The School of Social Work posted the honor on Facebook.

“Rai stood out among 21 excellent applicants as a leader in academics and service,” they wrote. “The T. Das Foundation awards this competitive grant to an Indian graduate student studying in the U.S. each year. Rai received $3,500 toward her educational expenses from the foundation, honoring her dedication to her program and outreach.”

As she nears the end point of her doctoral studies, she finalizes her dissertation, which bears many notations and sticky notes and is titled: Perceptions, Prevalence and Help-seeking Resources of Domestic Violence among South Asian Immigrants in the United States.

Rai stresses while the focus of her work was inevitable given her background experience, the formal shape of her research expanded at UGA.

“I didn’t know this was going to be my doctorate when I came in. Now I work with both men and women, and I want to know what men and women think about domestic violence.”

“I have always been close to my father, retired Major Pankaj Rai,” she says. “We have gotten closer ever since I lost my mom. I remember how he would always pamper me and support me in everything I wanted or dreamed of. The sky was the limit for me and he made sure I could dream big and achieve even bigger things. Even now, he is a patient listener and a best friend.”

Her father now lives in Hyderabad, India with her grandparents, and runs a computer language training center.

“I talk to them almost every day. It is this communication that keeps me motivated to keep going with my research,” she emails later. Her emails are ended with a tagline:

“Stop the violence, end the silence.”

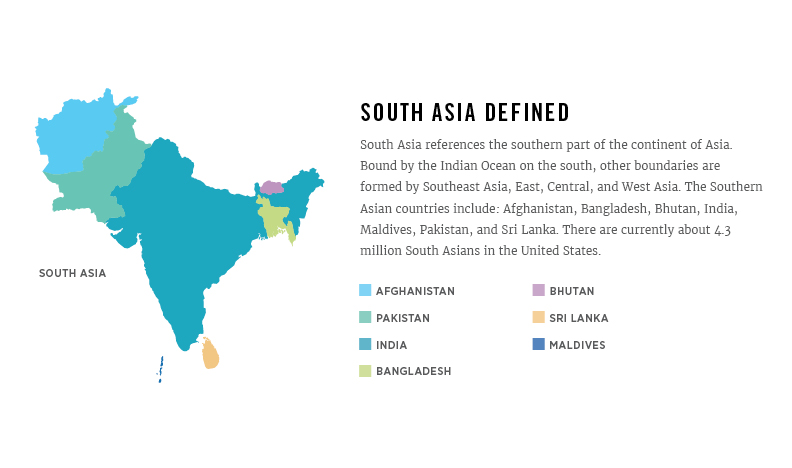

VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN Almost one third (30%) of all women who have been in a relationship have experienced physical and/or sexual violence by their intimate partner. The prevalence estimates of intimate partner violence range from 23.2% in high-income countries and 24.6% in the WHO Western Pacific region to 37% in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean region, and 37.7% in the WHO Southeast Asia region. There is evidence that advocacy and empowerment counseling interventions, as well as home visitation are promising in preventing or reducing intimate partner violence against women. http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE WITHIN THE SOUTH ASIAN COMMUNITY

According to UGA doctoral researcher Abha Rai, domestic violence refers to any form of abuse—physical, mental, emotional, verbal, sexual, psychological, economic or immigration-related that is perpetrated on a partner in a relationship. “Due to the patriarchal nature of the South Asian society, women are most often victims of domestic violence. Domestic violence rates are anywhere between 18-60 percent,” says Rai, who devotes her UGA research to exploring the daunting social problem.The complex issues are specific and worrying, she says. “South Asian women face unique challenges such as lack of familiarity with the language, inability to acculturate into the American society, social isolation due to limited or no friends, lack of financial independence that make them more vulnerable to experiencing abuse in comparison to American women.”