Why Scientist Bridg’ette Israel’s Path Blazing, Glory Making, Power Building, Family Recipe for Success isn’t a Secret Anymore

By: Cynthia Adams | Photos By: Nancy Evelyn

Take everything you think you know about fast-track researchers and scientific scholars and turn it around.

Myth 1: Scientists take a vow of poverty–self-inflicting monastic conditions of self-denial in the name of their art/ research/elegant thought.

Myth 2: They must shutter out all the things they enjoy— idle pleasures, fellowship–in order to focus upon the end goal and once there, publish or perish.

Myth 3: They are driven. Mono-manic.

Myth 4: They are introverts. Left-brained.

Myth 5: First-borns only should apply.

Think again. Hit the brakes. Back it up!

Meeting Bridg’ette Israel is like meeting the mythical monk in a red Ferrari.

She exudes Georgia red. She strides into a Savannah hotel lobby in a red dress with heels, flashing a megawatt smile with teeth even and perfect beneath red lipstick. She fixes her even brighter eyes upon people in the lobby and extends a firm handshake.

Um, this is not Bridg’ette Israel, the scientific researcher, right?

This is Bridg’ette Israel. Israel was born into a gregarious family on August 21, 1978 in Chatham County, Ga. “I love people; I would talk to that wall if nobody was in here,” she jokes.

Making it all look easy—like a piece of cake. (Her favorite, of course, is RED velvet.) Yet absolutely none of it, Israel explains with a cool smile that could just as easily be a grimace, was easy. Not a new marriage, the two children arriving at such a crazy-making time in the midst of graduate studies, the volunteer Girl Scouts work, the fierce love of home, the drive to steer this particular dream onto the runway, and land a doctorate at UGA. None of that was easy, not one iota.

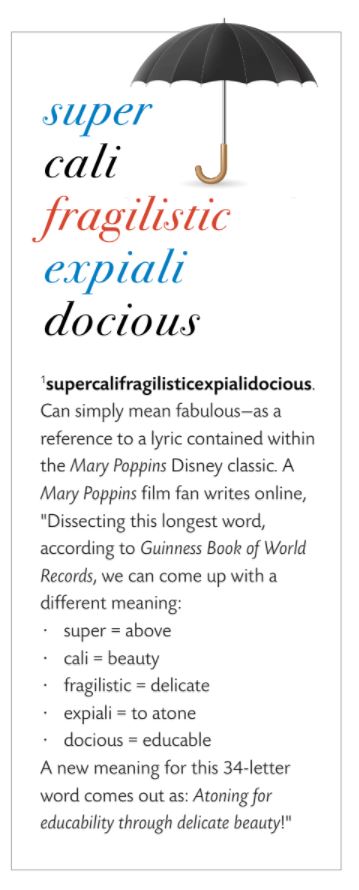

“Now, many of my little nieces, nephews and cousins have told me they will do it also!” Israel says, eyebrows high. Hopefully, I will be the inspiration for them,” she adds, beginning her supercalifragilisticexpialidocious story.

BRIDG’ETTE ISRAEL’S TIMING MAKES YOU SHAKE YOUR HEAD IN DISBELIEF

She inspires incredulity, starting doctoral studies while still caring for an almost newborn, three-month-old. In the midst of this, she and her husband, Jeremy Israel, had a second child. Bridg’ette Israel, who succeeds in reaching every dream she has hatched since growing up in Savannah in the midst of a large and loving family, likes to do things her way–and does. Multi-tasking is central to this woman’s life. Busy, she says smiling, is better.

At UGA for nine to 10 hours each day, Israel had to work to find balance “It makes you make the most of every moment. I tried to separate home and school, and came in (to the labs) early and left late. Some nights, I put the children to bed in order to do projects.”

Israel marvels at finishing her doctorate in pharmaceutical and biomedical sciences within six years.

“My kids…” she begins and falters slightly. “At times, I wanted to quit. But my family was very supportive. My daughter was like, ‘One day, you’re going to be a doctor, and then I don’t ever have to go to the doctor anymore and you can treat me when I’m sick!’ They were excited, and my motivation.” She laughs off that her toddler daughter made no distinction between an MD and a PhD. With a shake of her head, Israel adds with a hint of envy, “But to think about the people who didn’t have kids and weren’t married! On average it’s five years.”

What might overwhelm one inspires another. But what makes someone vow to defy all odds?

“Though most of my family is educated, a PhD is totally different. I am the first person in my family to have a PhD.” Powerful family ties–extending from her grandmother down the family line to her small children–drove this doctoral student and Alfred P. Sloan scholar on to greater horizons. Family made the difference, she stresses. So did the Bridges Program and the Alfred Sloan Scholars program.

But it isn’t supposed to be this way for the middle child. (Israel has two brothers and two sisters.) The dynamic within families is such that the middle child is not typically the highest achiever. Ha! Says Israel, smashing another myth to bits.

FIRST THERE WAS THE AWESOME MS. CALLAHAN, A QUIRKY SAVANNAHIAN WHO THOUGHT SCIENCE WAS GROOVY

A chemistry teacher at Windsor Forest High School in Savannah made all the difference for Israel.

“Science and math are like foreign languages you can get lost in very quickly,” Israel muses. Math had come easily to her. The language of science eluded her up until she met one key individual who changed everything and cracked the enigmatic code. Israel found herself in a classroom with Mrs. Callahan, a wildly exuberant science teacher unlike any she had ever met.

“The first day of school she came in dressed like Einstein, and I will never forget it. She was a little lady and so spunky and all excited about science! Math was pretty easy for me, but when I met her, I knew I was going to major in chemistry in college.”

Israel discusses Callahan having emanated excitement and engagement.

“She gave off the sense that every student in her class could do this…could understand science. I felt that for even myself.” It was another kind of epiphany to sit in such a classroom where failure was not a possibility: “Our students and children, they feed off of you (teachers’ energies). She was really good.”

Thanks to that one teacher’s encouragement and inspiration, Israel adopted a self-image of herself as a future scientist. Afterward, more powerful teachers kept finding her. It was remarkable, Israel says. Even destiny making.

As Israel’s siblings finished high school, they advanced onward as well. Her sisters attended Georgia Southern University. For a close-knit family, the college had the keen advantage of proximity. “It was in Statesboro, 45 minutes away. It was far enough you weren’t home, but close enough you can go home.“

Her oldest brother attended Savannah State and younger brother attended Morehouse in Atlanta. Israel, however, followed the others to Georgia Southern. On weekends, she could head home to visit her parents and family and enjoy low-country cooking.

Given a family penchant for Southern cooking, all of the sisters worked in the college catering service for extra income at Georgia Southern. Israel’s exuberant family was crazy about cooking and entertaining–and still is.

“We have parties for anything,” she grins. Israel holds up fingers, enumerating: “You get baptized, promoted, divorced, lose a tooth, it’s enough for a celebration! Put some meat on the grill!”

As Israel matured, it was uncanny how powerful mentors and circumstances kept finding her. “When I got to Georgia Southern, I had a professor, Dr. Jim Lobue. He was the person who told me, “At least, go get your master’s.”

She rolls her eyes, laughs, and says, “I did.” Israel chose a graduate school in Greensboro, N.C.

“It was weird because I first met my husband in Savannah the summer before I began the master’s program at North Carolina A&T State University. We exchanged numbers and kept in touch. He helped me move into my apartment in Greensboro.” The two began a courtship that ended in marriage before she finished her graduate degree. Israel was seven months pregnant with their first child when she completed a master’s in chemistry.

Israel’s best friend studied chemistry at NCA&T, and was entering the Bridges Program at the University of Georgia. Israel went along for a campus visit, strictly to support her friend. As a young married mother, Israel resisted her friend’s persuasive attempts to enroll with her. En route to Athens, Israel told her, “I said, I’m not going to start a doctoral program–a PhD was too much!”

All changed when Israel met yet another important mentor: Anthony C. Capomacchia. The professor persuaded Israel to follow her friend’s lead to UGA and join the doctoral program in pharmaceutical and biomedical sciences—after all, it would bring her back to Georgia, and within striking distance of her beloved Savannah clan.

Capomacchia also steered Israel to the Alfred Sloan program, suggesting Israel enter UGA’s doctoral program as a Sloan fellow. (See sidebar.) “It was an awesome experience,” she says. As in awe-inspiring.

When Israel returned the next time, it was as a doctoral student.

“I came to Athens in January of 2004 and my son was three months. I didn’t start that spring, but the fall of 2004.” And just because Israel was a Girl Scout troop leader from way back (Savannah is where the Girl Scouts were founded) with spare minutes on her hands, she answered another strong calling. As if it is the most natural thing in the world for a new doctoral student and mother to juggle another thing, Israel was inspired to do something unexpected with her free moments.

“I wanted to introduce Girl Scouts to the housing projects.”

So Israel did that—starting a troop in an Athens housing project. She admits ruefully, “The Girl Scout project was crazy enough shortly after I had my baby.”

But it all seemed outrageous. Israel was doing rotations through various labs as she pursued pharmaceutical and biomedical studies. She tended her babies and nurtured the scouting troop during stolen time. A sense of humor, and understanding husband, sustained her.

“I wouldn’t have thought it would be as great as it was,” Israel says. “I wouldn’t have asked for it to be any other way.”

ANOTHER ADVOCATE APPEARS: ENTER DR. CAPOMACCHIA

“At UGA, I visited different labs. Dr. Capomacchia was so influential; I knew I wasn’t going to be in anybody’s lab but his.” Israel describes him as “an amazing person,” who helped her find funds to attend conferences and to find opportunities.

Capomacchia also anchored her, and held her doctoral dream firmly intact. “I thought I was smart and everything, but not to the point that I was ever going to get a PhD. It was so important that he supported me, a total stranger—and to look at you and make you believe that you could do that thing. He is a great person. If someone is a good student, they always come to Dr. C.”

Israel first assisted on patent-pending osteoarthritis trials at the Complex Carbohydrate Research Center under a senior student.

“We did some trials, transdermal work with osteoarthritis, for a cream that helps rebuild the basic membrane,” Israel says.

Her second project involved working in veterinary science on wound healing for a corroborative project with scientists eventually including Capomacchia.

“A dog had severe burns and we developed ointments we thought would have the right kind of adhesion to that wound and developed bio-adhesive ointment. That same professor, Dr. Branson Ritchie, worked with the Georgia aquarium in Atlanta.”

The sick animal in question this time was a beluga whale named Gasper.

Researchers worked with scientists Ritchie and Capomacchia in developing a new formulation for an aquatic animal. As Israel was researching ointments for the burned dog, she realized the stability of an oil-based gel that adhered well. She tried the gel on different surfaces, employing various tests to see if it would adhere to the whale skin. She struggled to resolve a problem concerning how to get the formulation to release the drug.

“We tailored an ointment for an aquatic animal,” she says triumphantly. The work became the basis of her dissertation.

Finally—someone who might save the whales! (“I wish!” Israel chortles.)

“Serendipity is not normally a word applied to science,” Capomacchia, a professor of pharmacy, said in an interview published in Research magazine. “But sometimes a hunch or happenstance, or just being in the right place at the right time, can lead to exciting possibilities.”

BEA’S KITCHEN: THE MAKING OF A FAMILY LEGACY

Behind the scholarship and big dreams were good times in Savannah. Something was always cooking back home. In May of 2011, family members opened a restaurant at 2 l/2 East Lathrop Avenue in downtown Savannah.

They dubbed it Bea’s Kitchen.

“Bea’s Kitchen was named after my grandmother, who passed away last year (February 2010.) My maternal grandmother—she was my biggest fan,” Israel says. “She gave birth to 13 kids, 11 lived to be adults.”

Her grandmother, Israel recalls, married at 16 and lacked a formal education, and so valued it deeply for her descendants. “Most of her grandchildren went to college. When I got into the doctoral program, she then introduced me as, ‘This is the granddaughter who is going to be a doctor.’”

At age 86, Israel’s grandmother developed complications due to diabetes. She had poor circulation, and required an amputation in January of 2010. The wound would not heal.

“With diabetes, at some point it is very common to have a foot or leg amputation.” Many amputees die within the first year, Israel says. In February, only a month after surgery, her grandmother died.

“I am supposed to defend my dissertation in two months and she died. I didn’t want to take off time to mourn her.”

Israel describes how grief was funneled into her dissertation work on wound healing of aquatic animals— specifically, the sick whale at the Georgia Aquarium. She went a few times to the aquarium and observed the subject, and weighed the challenges of treating it.

Israel’s graduation was Mother’s Day weekend, a day she would typically have honored her mother and grandmothers. “It was emotional and special, fitting,” she says.

Now, because of her grandmother, Israel continues research in diabetic wound healing. Today she is at Florida A&M University, a historically black institution in Tallahassee, in a tenure track faculty position. More importantly, they recognize she is passionate about continuing her work with diabetes, though many of her colleagues are involved with cancer research.

“The name UGA just makes people want to give you a try,” says Israel. “Many places require you to complete a post doc before becoming a faculty member. “I feel like being a graduate of UGA said a lot to people. They were willing to give me a chance.”

Israel recently traveled to Texas Tech in Lubbock for further training in diabetic wound healing animal models and study protocols.

Yet the challenges deepen for research funding. “The National Institutes of Health shut down a couple of their entities, including research centers in minorities’ HBCUs. They’re starting to downsize; that’s going to affect us.” So she utilizes what is available at Florida A&M, while networking at other institutions like Texas Tech.

A THIRD VALUED MENTOR: DEBORAH ELDER

Israel discusses another important UGA faculty member, Deborah Elder, in pharmaceutical and biomedical science. “I was her teaching assistant. She was influential in my deciding to stay.”

Elder “saw my potential,” says Israel. Elder gave her a global viewpoint.

“Faculty members made it worthwhile. You run out of steam. But it made me prepare for the real world. The real world doesn’t care if you’re black, you’re a woman, you have kids, somebody dies in your family…whatever your job is, they hire you as the person who’s competent to do this job.”

IN MY OWN WORDS

My parents are Amos Sr. and Beatrice Johnson, who always taught us to value education. I am the third of five children. I earned a BS in Chemistry from Georgia Southern University (2000) and a MS in Chemistry from North Carolina A&T University (2003). May 8th, 2010 was such a memorable day for me and my family. This was the day I graduated from The University of Georgia with my PhD in Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Sciences. I began this program as a newlywed with an 11-month-old baby boy. During my second year, I was blessed with a beautiful baby girl.

I faced many challenges during my tenure as a graduate student at The University of Georgia, but I was determined to complete this program. I met Dr. Anthony C. Capomacchia while completing my MS at NCA&T. He is the minority recruiter for the Bridges program and Alfred P. Sloan Scholarship. Dr. Capomacchia genuinely cares about the needs of the students. After meeting him, I knew I wanted to work in his laboratory. Dr. C, as he is affectionately known, is an awesome person. As my research advisor, Dr. C. was always helpful in designing research protocol and motivating the lab members

As an Alfred P. Sloan Scholar, I was afforded the opportunity to attend one of the best Teaching and Mentoring Symposiums in the country. October quickly became my favorite time of year during Graduate School because I knew the Southern Regional Education Board was just around the corner. Every year just when you had enough of research experiments not working out and your academic environment became a bit overwhelming, it was time to go to the SREB Teaching and Mentoring Conference. It is difficult talking to your family and friends about the PhD journey if they have not been through it. This conference provides that family for many of the Sloan Scholars. I met people from universities all over the United States and together we are changing the face of science in this country.

As a junior research faculty member, I strive to positively impact the world of scientific research. My research focus is diabetic wound healing. I will dedicate this work to the life and legacy of my maternal grandmother, who passed away from complications from a leg amputation (due to failure in wound healing treatments) just three months before I graduated from The University of Georgia.

—Bridg’ette Israel

ALFRED P. SLOAN FELLOWS AND UGA

“The Program began when a proposal I submitted to Director Ted Greenwood of the Sloan Foundation was funded in 1999,” says Anthony C. Capomacchia, the director of the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Minority Doctoral Program at the University of Georgia.

“The stipulation was that I continue to recruit one minority student per year; Sloan would fund additional students up to a limit of five students by means of a fellowship. Sloan requires that each department contribute to a student’s funding since it expects a buy-in by departments or University to support minority graduate education. The student becomes a Sloan Scholar upon accepting the fellowship,” Capomacchia explains.

“Fellowship funds are awarded directly to the student and held in an account by NACME (National Action Council for Minorities in Engineering) and accessible to the student through me to defray the costs of their graduate education; tuition, housing, books, research travel, etc.” The Sloan Foundation’s psychosocial and financial impact is significant, Capomacchia explains. “Since inception of the program the Sloan Foundation has funded, in part, 40 minority graduate students here at UGA.”

Sloan’s reach also grows. Five Sloan scholars entered UGA in fall 2011. According to Director Capomacchia, the Sloan Foundation has supported 21 doctoral dissertations, five master’s theses, and 33 publications between 1992 and 2010. “These results led to additional funding by the UGA Graduate School and to a Bridges to the Doctorate grant for minority graduate students.”

In addition to personally mentoring each student, Capomacchia still attends an annual fall event called the “Compact”— the same event that so deeply affected Bridg’ette. It is fully funded by the Sloan Foundation.

Five Bridges to the Doctorate students, also UGA Sloan Scholars, received UGA doctoral degrees, including Bridg’ette Israel, Leah Williamson, Shawn Blue, Tucker Swindell, and Pamela Garner.