Children Playing their Way to Health

By: Cynthia Adams | Photos By: Nancy Evelyn

Richard Christiana’s hope to avert epidemics of diabetes and cardiovascular disease

Christiana believes the outdoors is a place where children can be freer to explore and construct their own play without the pressure of team competition. This play can lead to lifelong health.

America’s children munch and snack their way through the day—at drive-throughs, at the computer desk, and while watching television. Their intake and activity levels are as uneven as a playground see-saw.

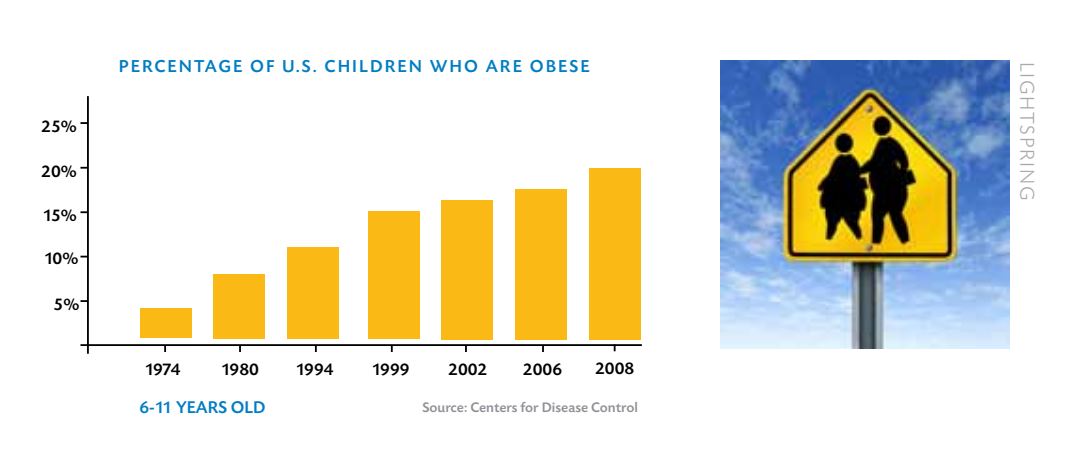

Portion sizes are climbing. Caloric, or energy, intake is climbing. Yet energy expended, and the quality of foods consumed are declining, along with the traditions of children having breakfast, sitting down to eat dinner with their families and being active. These trends mean disease-filled futures. Obese children are showing evidence of risk for coronary disease and pre-diabetes.

Stakes are high. How long children will live, and how healthy they will be, are in jeopardy. There is clear indication of costly dangers: federal statistics placed the 2008 health care financial toll of obese children and adults at $147 billion. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 17 percent of children are obese. State trends for the years 1985-2010, indicate that percentages of obese adults in southern states are the worst (Georgia’s obesity percentage is 29.6.)

Richard Christiana climbing boulders at Boat Rock in Atlanta

FEARFUL FORECAST: HEART DISEASE AND DIABETES

If childhood morbidity and disease won’t get our attention, Richard Christiana makes one wonder exactly what will.

There is a war without a name, taking fatalities and a toll on America’s well-being. It’s the battle of the bulge. “Baby boomers say their biggest health fear is cancer,” the Associated Press (AP) warned this past summer. “Given their waistlines, heart disease and diabetes should be atop that list too.”

The battle is familiar to many Americans—truly more like a siege if you analyze the numbers for obesity, with one-third of adults (33.8 percent) at that percentile. Adults joke about their “love handles” and pat middle-aged “meno-pots”—while privately buying the latest diet book or considering fat melting technologies. Others accept an expanding waistline as the new normal.

According to health science writer Rhonda Mullen, the scope of this dietary and lifestyle disaster is global. “Two hundred twenty million people worldwide have diabetes,” she writes, “with that number expected to double by 2030. More people die worldwide and in developing countries from cardiovascular disease and diabetes than from malaria, HIV, and tuberculosis worldwide.”

Even the experts struggle for acceptable language in addressing a burgeoning American epidemic.

Researcher Richard Christiana, who is completing his doctorate in health promotion and behavior at the College of Public Health, agrees that it is difficult to talk about obesity in normal tones, if at all, without igniting resentments or hurt feelings. Weight is one of the last taboos.

Most especially, Christiana says, this is a “hot-button” issue when speaking about children who are obese. Meanwhile, America’s children are growing larger and potentially facing a future of compromised health.

Here are the numbers for American children:

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) spells out disastrous statistics—the number of overweight adolescents has tripled since 1980. The prevalence among younger children has more than doubled…and the long-term consequences “increase the risk of developing high cholesterol, hypertension, respiratory ailments, orthopedic problems, depression and type 2 diabetes as a youth.”

Another health-compromising concern worries Christiana. “There is also the issue that these children will develop these conditions at younger ages, like before and during their 30s,” he says. An overweight adolescent faces a 70 percent risk of becoming an obese adult, the HHS writes. And the CDC adds, “During the past 20 years, there has been a dramatic increase in obesity in the United States, and the rates remain high.” Medicare costs are surging as obese adults grow sicker faster. The AP predicts the burden upon Medicare is unprecedented, with aging boomers tipping the scales at unprecedented and unhealthy levels.

Can we blame our woes on fried chicken, gravy and Mama’s golden biscuits? Do we just pour on the gravy and hope for a diet miracle? Not if we want our children to have a fighting chance at wellness, says Christiana. Push-backs may be just as key as pushups—as in, push back from the table.

Just put the biscuit down. Now. And tell your child it’s time for play.

CORRELATING OBESITY TO BISCUITS AND OTHER CHOICES ISN’T THAT EASY

You may forego the biscuit or bagel, depending upon where you live and your bread of choice. But in truth, obesity isn’t quite as simple as caloric consumption. A bewildering number of factors come into play with obesity: genetics, economics, activity levels, culture and media, and eating patterns.

“Obesity is not a single-factor issue,” Christiana explains. And there is another contributor: lifestyle. Christiana is loath to finger a single, stand-out cause. He sighs, making observations carefully, codifying his comments, like a food anthropologist. (He actually earned a degree in anthropology at SUNY Albany.)

“The causes include stress, sedentary lifestyle, dietary choices—fried, Southern, country fare.” He continues. Obesity is generational as well.

“The grandparents and parents, were physically working, active, not watching TV. People were out walking and more engaged with the outdoors. You think about issues of community.” Communities, he discusses later, have changed. Sidewalks and playgrounds became passé. Children today are seldom allowed to simply play in the great outdoors.

Whippet-thin, dark haired and well on his way to wrapping up a PhD, Christiana speaks in politely low tones as he discusses childhood obesity research during a meeting in a downtown Athens lobby. Never once does he use the verboten f-word: Fat.

The language and semantics of obesity are especially charged with meaning and hurtful. The word “fat” was in every school bully’s repertoire.

Yet in truth, school children of today are larger and frequently obese. Their meals are more often from restaurants and outside the home. Children consume more snacks and calorie-loaded beverages. The outcome is disastrous.

Governmental research indicates fewer than a quarter of American youth get the required five servings of vegetables. When they do eat a vegetable, it is most often in the form of a fried starch. “Nearly half of all vegetable servings are fried potatoes,” states one assessment of dietary habits among youth.

Worse yet, there is this tremendous reluctance to address obesity in children. This inhibition exacerbates medical intervention. “Physicians have always expressed that addressing obesity is such a difficult issue. Part of this has to be how touchy this issue is; so who is the right one to tell parents?”

Christiana respectfully drops his voice as a rotund business man makes his way through the lobby. “It’s easier to address this [social issue] with tobacco than with obesity. It’s a very, very thin line….”

Christiana’s dark eyes dart towards the man, sweep the lobby, and he resumes speaking.

“Chronic disease problems are caused by this, by obesity. I don’t think the public understands the impact on insurance, etc. Everybody wants to reform health care, and everybody’s afraid about these children. Many of these children already have adult health conditions…. It’s like everybody’s paying out of pocket for this problem right now. The public don’t realize yet the implications for everybody else. It’s a drain on the economy, the health care system, and it will affect everybody else.”

AT LEAST, BIRD WATCHING KEPT HIM OFF THE SOFA

Christiana may be a slim adult today because of genetics, or diet, or simply the fact that his father loved the great outdoors and bird watching. As a kid growing up in upstate New York, he was one of five children. The family was active, though not necessarily competitively athletic. “We went hiking, did bird watching.”

He played soccer and took walks in the woods near his home. But he also liked to spend time watching TV and playing videogames—describing a fairly typical childhood.

(Where does an adult go to play soccer, he asks later? “For adults to keep up an activity like soccer they need to know others who have the same interest, and need a place and time for everyone to meet. Whereas with going for a walk in the woods, or bird watching, all you need is yourself. It seems like there are less factors or constraints to consider when trying to do these activities versus many sports.” He prefers to focus upon noncompetitive activities that people can sustain over a lifetime.)

Christiana says “I actually started with skiing a couple of times in college and then moved on to snowboarding. College is also where I started getting into rock climbing and backpacking.”

Activity, he explains, is an important aspect to health and wellness—something simple that most of us grasp even when not incorporating it. We commute rather than walk or bike to work. We sit for long hours at computers and televisions. Perhaps one piece of the answer for urban dwellers can be designed into our cities and communities. It even has a name: active communities.

“Engineers and city planners say we can design and promote active living. They have a term, ‘active communities,’ or ‘healthy communities’ designed for that purpose. There are “Safe Routes” to school to get kids to walk to school.” Christiana envisions a re-imagined America, with old fashioned sidewalks and greenways that will get more people off the sofa and out of doors.

His favorite book, Last Child in the Woods by Richard Louv, is prescient. “Louv’s book,” Christiana explains, “concerns nature deficit disorder, a term coined in the book that refers to the psychological, behavioral, emotional and physical consequences of children not having regular contact with nature.” Christiana says his father’s emphasis upon bird watching and family hikes had the benefit of providing contact with the natural world. It balanced his childhood fascination with passive television watching.

“The solution to the problem, if there is a solution, is multi-faceted,” Christina says. “Everything is interrelated. It’s a lifestyle change and a different way of thinking about everything. It is about changing the American ideal.” A shift in ideas about the American lifestyle is what Christiana advocates.

“It’s not the American way; there’s all this research saying all the values of playing video games enables them (children) to be problem solvers. There’s some benefit of technology for the young. We embraced more of our technology as we started to abandon the natural world, especially as children.”

Christiana returns to Louv’s book, but adds, “I’m not touting the natural moderation. It’s also not bad to have and make use of technologies (i.e. video games.) Just don’t neglect the benefits of taking a walk outside and enjoying nature. This is something technology cannot provide you, but is something that has always been around.”

Kids at play on the Colham Ferry Elememtary School playground. Will Evelyn, Dakota Hamlin, McCrae Claas

CAN WII FIT CHANGE THE DYNAMIC?

“Physical activity is so simple. With Wii and other games, why not get children more active while they’re playing, not just sitting there with a controller?” Christiana discusses the simulation of experiences and value of making video games more interactive.

This leads to a new concept in changing the game on a large scale: in this case, waging a community intervention in southern Georgia. For the past year, Christiana worked with YMCA parents in Moultrie, Ga., conducting focus groups and trying to help the parents overcome barriers to healthier food and activities for their children.

“Communities are seeing problems with child obesity. Archway got this partnership together, which started out as a relationship between Colquitt County and Archway and UGA’s College of Public Health, addressing this issue.” The grant-funded project is part of the Archway Partnership initiatives.

Created in 2005, the Archway Partnership was born of a repurposing of the traditional land-grant university, agricultural extension model, in order to address a wider range of concerns faced by communities. “The Archway Partnership is a process to connect higher education resources to community-identified priorities,” Christiana notes, saying that Moultrie was the first community to engage in this particular type of relationship. The priorities differ by need.

“Archway is also a community capacity building engine, which may involve building tourism, consumerism, health, or transportation. The idea was to team up with the College of Public Health,” he explains.

Christiana says the community leaders came to the table to forge a meaningful project with the researchers. “This ensured full community buy-in to what was happening, and ensured a more positive outcome,” he adds. He traveled to Moultrie twice monthly to cement relationships with parents and key community figures. “I was down once every other week with the childhood obesity project for one year through last summer,” he explains. Marsha Davis from the College of Public Health is the lead researcher on the project, and Christiana is the graduate research assistant.

In the process, he worked towards a community intervention—definitely a first in Moultrie if not the entire state. “To my knowledge, this particular thing through the Archway Partnership hasn’t been done before in Georgia,” Christiana says.

“I’ve never done this before and it was a great experience,” Christiana says, “because I was able to see a community-based participatory project get started right from the initial stages. In classes, we learned about this type of research, but what we didn’t learn is how to build these partnerships, what a project like this really looks like on the ground, and how long of a timeframe it takes to do this type of research.”

The design for the eventual intervention involves working with the Moultrie community as advisors to their community leaders, helping achieve outcomes they defined for themselves.

This concept—community-based participatory research—is ground up and therefore a dynamic shift, which excites Christiana. It addresses the old problem of research being done without a buy-in by the community or participants, he explains. “This time, it’s different, doing research with the community rather than in the community.” He hopes this “assures a greater sustainability of the outcomes of the research long after the researchers leave.”

Christiana is also involved in conducting health needs assessments in Pulaski and Sumter, Ga. He is uncertain exactly where that will lead, and patience is one of the lessons learned. “It’s incredibly slow. It’s not necessarily the number one issue on everyone’s mind, but it’s getting people to agree when there are various sectors.”

Yet there are innovative developments in Athens and other communities, Christiana points out. And these suggest hopeful shifts for Moultrie. Community gardens, like those in Athens, are “a promising solution to healthier eating and physical activity,” he says. Creating a local farmer’s market in Moultrie, rather than exporting all the fresh produce grown in the fertile climate of southern Georgia, is another.

“Everyone’s receptive, in terms of bringing in farmer’s markets and making sure there’s fresher produce available to the public. A lot of the parents say they want that—a lot of the parents ask, ‘Why do we not have fresher produce?’”

THE PROBLEM OF EXCLUSION WITH TEAM SPORTS AND ACTIVITIES

For his own dissertation research, Christiana focuses upon early adolescents’ experience “exploring the outdoor environment.” He is examining their motivations, intentions and experiences concerning cycling, hiking and playing outdoors.

Team sports and competitive events remain popular in America but there is a definite issue of exclusivity. “A lot of kids are not sports-gifted, so they are less active.” (And, he adds, heavier children often don’t get picked for the ball team, or invited to play other team sports.) This may exacerbate the problems obese or less active children face, Christiana discusses.

“How to get those kids involved? I would say it’s through non-competitive activities. Climb rocks, walk, and hike. It has a different feeling to that activity.”

Solutions do emerge, the researcher promises. But this is a different way of teasing out solutions. “It’s very different to design solutions (and try to impose a model) than to participate in this with the people.”

Christiana explains how obesity is a systematic problem, not an isolated health problem. “That is part of the challenge and part of the interest factor. That’s what drew me to this area [of research]. There’s never going to be a pure solution or a cure for childhood obesity.” When he completes his doctorate in 2012, Christiana will continue his research in academia.

He received the UGA Rotaract Student Service Award in 2011 after nomination by the Graduate School for community service, leadership, and academic excellence.

IN MY OWN WORDS

To this point, public health has focused more heavily on getting kids to participate in structured activities (team sports and physical education classes) in school. The issue is that many children, who are not naturally athletically gifted, may tend to shy away from these types of activities, for fear of being teased or unaccepted. In effect, they get left out.

My intended work is to fill a gap in the public health research related to physical activity, by exploring children’s participation in non-competitive, outdoor activities. These tend to be spontaneous and allow children to self-facilitate their participation and level of engagement. They also tend to more inclusive, and naturally provide an opportunity for children to build the skills that are necessary to participate in other forms of physical activity. The outdoors is a great place to study children’s noncompetitive physical activities, since children tend to play more vigorously when they are outdoors…the outdoors also provides a place where children can be freer to explore and construct their own play without adult involvement. This stimulates creativity and builds other important skills.

I grew up playing several team sports, including soccer, football and ice hockey. When I look at the types of activities I do as an adult (hiking and cycling) I notice they are noncompetitive. I don’t even know the last time I even played backyard soccer or football—and I think this may be the case with a lot of adults. Not that organized team sports don’t provide children with many skills, because they do. I just think getting children involved in more unstructured outdoor activities could promote their continued engagement in physical activity as they grow older.

-Richard Christiana

THE GREAT FRENCH KETCHUP CAPER: Legions of French Children are Going to Get Healthier by Rescinding Rights to Ketchup

Can Banning Ketchup help French children stay svelte? Blame it on political backlash. (Remember “Freedom Fries”?) Nothing is more American than ketchup. The French have decided they are taking strong measures to ensure the billion meals served annually in French schools are healthier—and more French—so they’re banning ketchup from school meals. According to The Los Angeles Times, the ban is meant to promote healthier diets among school and college-aged students. Kim Willsher reported in the Times during October, 2011 that the French government has officially moved to restrict the use of this American condiment in their cafeterias. Numerous news agencies in Europe and the United States howled at the news. One food blogger wrote that American ketchup is now “condimenta non grata.” Abroad, the European press took issue with the ban. The Los Angeles Times, NBC News and The Huffington Post ran features on the condiment controversy, speculating about enforcement and the French food police. Published reports stated that France is McDonald’s largest European market. “In an effort to promote healthful eating and, it has been suggested, to protect traditional Gallic cuisine, the French government has banned school and college cafeterias nationwide from offering the American tomato-based condiment with any food but—of all things—French fries,” Willsher reported from Paris. “As a result, students can no longer use ketchup on such traditional dishes as veal stew, no matter how gristly, and boeuf bourguignon, regardless of its fat content. Moreover, French fries can be offered only once a week, usually with steak hache, or burger. Not clear is whether the food police will send students to detention if they dip their burgers into the ketchup that accompanies their fries. “France must be an example to the world in the quality of its food, starting with its children,” said Bruno Le Maire, the agriculture and food minister.”