Fully Tested: Danielle Jensen-Ryan and Her Fight Against BRCA

By: Cynthia Adams | Photos By: Nancy Evelyn

At age nine, Danielle Jensen-Ryan coped with becoming a caregiver to her ill mother. At age 34, her mother battled late stage colon cancer, and subsequently, developed late stage breast cancer by age 47. Jensen-Ryan’s childhood was shadowed by the specter of cancer. Now it had reared its head again—but it was not, she said firmly, going to stop her.

Last October, Danielle Jensen-Ryan was at Lake Lanier Islands attending the Graduate School’s Emerging Leaders Program when she shared a defining experience: Jensen-Ryan carries an extremely rare genetic predisposition for cancer known as BRCA 1 and BRCA 2. She openly discussed undergoing genetic testing and the aftermath.

What Jensen-Ryan did not add was that she had recently had an additional surgery related to BRCA 1 and 2. This was her first professional meeting post-surgery, and she was still dealing with the physical aftermath. But not anyone at Emerging Leaders would have guessed it. Jensen-Ryan was fully engaged in the weekend long seminar which is an intensive, physically active, and experiential workshop.

In November of 2011, Jensen-Ryan was a newcomer to Athens having relocated from the West with her husband, Jess. “We had just moved to Georgia and left everybody we knew in Wyoming,” she explains. She was in her third year of marriage and entering the first year of a doctoral program in environmental anthropology.

Her mother urged her to undergo genetic testing for the BRCA 1 and 2 genetic mutations.

The test results returned on October 27, 2011. It was only a little over a week until her 25th birthday. Jensen-Ryan received news that she tested positive for BRCA 1. “They immediately suggested a mammogram,” Jensen-Ryan recalls. She complied; the mammogram revealed an abnormality.

Just before Christmas, she had an ultrasound of the area in question. A biopsy was scheduled for January.

When Jensen-Ryan learned about her condition, she shared it with Margie Floyd, the Anthropology department’s graduate office coordinator.

“She immediately helped organize support for me,” she says. Jensen-Ryan was offered a graduate fellowship with online work, which meant she could manage to navigate both her classes and medical issues.

Danielle Jensen-Ryan

“I remember meeting with my then advisor and asked if we could go outside to discuss it. My sunglasses would tint in the sun and no one could tell I was crying.” At this point, she had not known any of the people offering emotional and practical support for more than a few months.

“I love to work, and love hard work. That just came from my Wyoming background. I didn’t want it to be like, ‘Oh, poor Danielle, she got diagnosed with BRCA 1 and had to drop out. ‘I’m a fighter. Even facing adversity. There was no other way. I wanted my PhD!”

Jensen-Ryan met with professor Laura German. “I grew a relationship with her from the first classes.” She decided to change her dissertation research focus and chose her for an advisor.

She underwent a total of 11 biopsies. “I was so overstressed. I met with Dr. Steinhaus in Atlanta, and Dr. Cramer at the women’s clinic.” Although her biopsies were cancer free, the medical team set a date for her to undergo bilateral mastectomies for June 12 during her next summer break.

It was feared that cancer was a given if she wasn’t proactive about surgery.

During the Christmas holidays, Jensen-Ryan and her husband made a difficult trip back to Wyoming. “I went home for Christmas. When I talked about it at first to people, I’d always break down and cry. My mom told everybody back home what was going on.”

She describes how she felt—completely exposed—and vulnerable. The news was still raw; it was difficult to handle sympathy without breaking down. “I’d go into the bank (back home) and I hadn’t told anybody about my BRCA 1 and yet all the ladies are telling me they are sorry. I remember walking out of the bank feeling terrible and telling my mom, ‘I don’t know if I want everybody to know.’ Now I embrace it! I remember my mom would tell everybody that she was going through cancer at the time she was ill. I got upset and asked her why she would do that. It wasn’t embarrassment—I wanted to cry because it was so hard.”

Her husband, Jess Jensen-Ryan, whom she had met as a college debate partner at the University of Wyoming, was not only an advocate but a best friend and her most trusted confidant. The entire family discussed having preventative surgery, which would mean a bilateral mastectomy and reconstruction.

“My family’s freaking out, I’m freaking out. The family was split on what I should do.” Yet her husband remained supportive from the beginning. He had witnessed her mother’s cancer fight. “He did not want me to go through chemo and radiation, and face the lasting effects of these treatments. He knew I could make it through the surgeries and come out on top.”

The couple talked it through, considering all aspects. Jensen-Ryan relived her mother’s past experiences and her own childhood. She also felt the pang of how her decision would affect her and her husband. “I remember terribly intense conversations. I felt so guilty.”

There was also the stress of not having elective surgery then developing full blown breast cancer. “Jess and I said no thank you. We wanted the double mastectomy and reconstruction. I had a really hard semester,” she says without a trace of selfpity. Her grandparents came from Wyoming to check on her. Then she decided to start a Facebook page and called it “Team Danielle.” She began drawing strength from a virtual community of supporters.

She still maintains a growing legion of online supporters. “Check on Facebook,” Jensen-Ryan says. “I had over 150 people following me online. I kept it active in order to communicate with close friends and people from my hometown.”

After surgery in June, her family flocked to support her following nearly nine hours of surgery.

“My mom flew down. She stayed with us for three weeks. Jess’s grandma flew down two weeks after that and stayed two weeks…they were wonderful. It was a lot longer recovery than I expected.”

Jensen-Ryan underwent additional implant surgeries and reconstruction. Her maternal grandmother returned to help her through reconstructive surgery. She began physical therapy to rebuild lost muscle. Immediately post-surgery, she could no longer steer her straight-drive pickup truck.

She returned to campus for a meeting with German, her advisor. Jensen-Ryan had to navigate the pain of driving and what it required.

“I got a traffic ticket that day,” she adds ruefully. “I still couldn’t wear the seat belt properly.” Her fellow graduate student, Francesca Judd, helped carry her books. “Francesca was my right hand. I couldn’t wear a backpack because I was still healing.” A physician arranged for her to get a handicapped sticker for easier access to her classes. She kept up with medical screenings and continued healing over the next two years.

“I didn’t feel I was really over the breast surgeries until the beginning of 2014. It took a long time to get back to myself. Meanwhile, I got a blood test and transvaginal ultrasound every three months.” Her medical advisors were concerned about her added vulnerability to ovarian cancer. It was difficult to detect until it reaches stages two or three. “And even then,” Jensen-Ryan explains, “with all the screening, they only detect one in 10,000. So we met with counselors and with doctors and then decided we would settle on adoption.”

When something popped up on an ultrasound last year, the Jensen-Ryans decided upon a preemptive hysterectomy. “It took the wind out of my sails for four months. Given I was so high risk there was no reason to take a chance. I didn’t want to pass on the BRCA 1 to children,” the couple mutually decided. The hysterectomy date was set for July 29, 2015.

Jensen-Ryan decided to start a Facebook page called “Team Danielle.” She began drawing strength from a virtual community of supporters. “I had over 150 people following me online. I kept it active in order to communicate with close friends and people from my hometown.”

She began mental preparations with meditation exercises.

During the surgery, they had to also remove an infected appendix. Then she began hormones, as she entered into surgical menopause. But the recovery was harder than she had imagined.

And Jensen-Ryan, who was an old hand at conducting interviews and well-aware of the power of communication, decided something else was needed: “We need to have an open dialogue.”

By the fall of 2015, she was planning to further that dialogue and begin her own BRCA support group for college women (known as BRCAn’t Stop Me.) When she talked with new friends at Emerging Leaders, she openly discussed her medical experiences. She also shared that she was successfully moving towards completion of her doctorate despite all.

By the fall of 2015, she was planning to further that dialogue and begin her own BRCA support group for college women (known as BRCAn’t Stop Me.) When she talked with new friends at Emerging Leaders, she openly discussed her medical experiences. She also shared that she was successfully moving towards completion of her doctorate despite all.

“I’ve gotten over $25,000 in funding; I just want to show that you can do it, even if you go through the hardest things imaginable.”

Jensen-Ryan attributes her perseverance and success to many important others. First, she speaks of her husband Jess, and his endless supportiveness and kindness. Then she mentions the pluck of her parents, Steve and Michele Jensen. Their steadfastness as a couple has been a powerful example of grace under pressure.

She discusses numerous essential people on her medical team in Athens:

“Dr. Gary Glasser at the University Health Center’s Women’s Clinic helped me tremendously through my ovarian surgery with referrals, decisions, hormone replacement therapy.” Her primary care doctor, Dr. Chadwick Palmer, at the Medical Clinic Red, provided me with regular care and with care after my surgeries.”

Dr. Margaret Cramer (past head of the UHC Women’s Clinic) garners highest praise. “I spoke with her just last week on the phone and she is a lovely person and was so helpful with my diagnosis and follow-up after my breast surgeries. She also helped me apply for and receive a handicapped parking spot on campus for a semester because I was unable to carry a backpack—she was very detail oriented and thought of all of my needs.”

There were many others, too, who were charter members of Team Danielle. “Lauren Richards, at the Loran Smith Cancer Center, helped me with counseling, both genetic, and with sessions before and during my breast and ovarian surgeries.

She’s absolutely amazing and has said the Center will support BRCAn’t Stop Me in any way possible.” The support of her professor and advisor, Laura German, was something that kept her on course, she insists.

Jensen-Ryan emails: “She helped me design two courses from home to take while I was unable to come to campus for class, cooked me meals, advocated on my behalf academically, etc. She is an AMAZING lady who I’m pretty sure saved my academic career and she was willing to work with me while I was recovering. “

“She is a remarkable young woman,” says German, “and juggled the impossible strains on her time and body through her own positive attitude, her sheer determination, and her remarkable ability to balance and pour energies in equal measure into work, health and (yes, even!) community service. Students with far more to be thankful for struggle with graduate school, and Danielle has advanced through her program of study with distinction despite the odds. If I helped her in this journey, it was in very small ways that may have gained significance through the unique circumstances surrounding them.”

And then there was Judd, a fellow graduate student. “This lady was my original cohort and was amazing at helping me through my journey,” says Jensen-Ryan. “She picked me up for our classes every Wednesday and Friday (because I was still only a second year at the time and had course work) and carried my books for me. She regularly brought me food and walked my dog, Tuni, for me. She is a godsend and also agreed to be the Vice President for BRCAn’t Stop Me this semester.”

What are BRCA 1 and BRCA 2?

A woman’s lifetime risk of developing breast and/or ovarian cancer is significantly higher if she inherits a harmful mutation known as BRCA 1 or BRCA 2 agree medical research groups.

Genetic testing can identify the presence of the heritable gene defect best known as BRCA 1 and BRCA 2.

What is this?

“BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 are human genes that produce tumor suppressor proteins. These proteins help repair damaged DNA and, therefore, play a role in ensuring the stability of the cell’s genetic material,” reports the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta, Ga.

While relatively rare, this mutation renders cancer-preventing (or tumor suppressor) proteins unable to help block abnormal growth in cells. The genes can be inherited from either parent. Those who possess mutated copies of the BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 genes have a higher lifetime risk of developing breast cancer. The mutations potentially affect 5-10 percent of breast cancer cases.

How much does having a BRCA 1 or BRCA 2 gene mutation increase a woman’s risk of breast and ovarian cancer?

The statistics are alarming. Breast cancer occurs in roughly 12 percent of the general population adds the CDC. “By contrast, according to the most recent estimates, 55 to 65 percent of women who inherit a harmful BRCA 1 mutation and around 45 percent of women who inherit a harmful BRCA 2 mutation will develop breast cancer by age 70.”

According to the CDC, the harmful mutation can result in a potential for also

developing ovarian cancer. “As a result, cells are more likely to develop additional genetic alterations that can lead to cancer.”

The CDC website adds that specific inherited mutations in BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 are also with increased risks of several additional types of cancer and are responsible for nearly a quarter of all breast cancer cases.

“A woman’s lifetime risk of developing breast and/or ovarian cancer is greatly increased if she inherits a harmful mutation in BRCA 1 or BRCA 2.”

In the instance of ovarian cancer, as many as 39 percent of women who inherit a BRCA 1 or BRCA 2 mutation have a much higher risk of ovarian cancer than the general population.

“Although in some families with BRCA 1 mutations the lifetime risk of breast cancer is as high as 85 percent on average this risk seems to be in the range of 55 to 65 percent. For BRCA 2 mutations the risk is lower, around 45 percent.”

They add that breast cancers linked to BRCA 1 or BRCA 2 mutations also can occur in much younger women.

Talking Policy and Science: How Danielle Jensen-Ryan Will Rope and Steer Social Action

She is cheerfully, politely, and dauntlessly willing to wade into difficulty. UGA graduate student Danielle Jensen-Ryan is unafraid of it. Her upbringing made her resilient. Born and raised in Cheyenne, Wyoming, she enjoyed the brutal beauty of the untamed West. She speaks with pride about the native, inherent toughness of those who settled there. As a tyke, she was attending the world’s largest outdoor rodeo during Frontier Days before she could even walk.

Danielle Jensen-Ryan comes from sturdy frontier stock. (Her great-grandmother, now in her late 90s, was born in a covered wagon in Colorado.) “I hope to utilize my years of experience advocating on behalf of social justice and environmental issues to translate into a career working together with other decision-makers to positively influence our country’s future for years to come.”

She cut her research teeth working on controversial subject matter. Before entering UGA’s doctoral program in Environmental Anthropology, Jensen-Ryan focused upon the environmental and health impacts of uranium mining in her home state of Wyoming. During her graduate work at the University of Wyoming, she examined how underground miners and their families were affected by what was called “radiation cancer.”

She met with mining families and individuals who had experienced the aftermath of underground mining. It was emotionally difficult to survey over two dozen affected individuals, learning how they had coped with the harsh realities of sickness and, too often, death.

“The social activism in these local Wyoming communities was a piercing, emotional example of ways in which collective action can influence state and federal laws, Jensen-Ryan explains. “I was able to work with local uranium miners, CEO’s of uranium companies, the head of the Wyoming Miner’s Association, and the Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality to develop recommendations for Wyoming’s legislature concerning uranium mining issues,” she says.

Since last fall, Jensen-Ryan employed her communication skills to address another environmental controversy in the Southeast: water policy. Using ethnographic interviews she met with stakeholders throughout the state of Georgia. Her dissertation work attempts to bridge environmental science and policy, seeking the common ground. She finds that “ethnography uncovers systematic cultural complexities and is particularly suited to research the ‘messiness’ of politics.”

“Without talking to individuals directly involved with water policy in Georgia, I would always be getting a secondhand interpretation of what occurred,” she explains. “This is what makes anthropology incredibly helpful when you are trying to figure out what is actually happening ‘on the ground,’ rather than what a publication, newspaper article, or, in my case, law, actually dictates.”

A Water Plan with Many Crosscurrents

In 2008, Georgia passed the Statewide Water Plan. Contributing to the need for such a plan were significant issues, such as salt water intrusion, decreased river flows, increased agricultural irrigation, local water system stresses, and a long list of additional concerns.

In 2008, Georgia passed the Statewide Water Plan. Contributing to the need for such a plan were significant issues, such as salt water intrusion, decreased river flows, increased agricultural irrigation, local water system stresses, and a long list of additional concerns.

Jensen-Ryan asks, “Well, what happened next? Has this been effective? What occurred because of this plan? My research is interested in outcomes, but is also interested in how law comes into place as well. Especially regarding how and whether environmental science becomes policy.”

Her fieldwork took place over eight months. She examined three water policy case studies in the state of Georgia: the Comprehensive Statewide Water Policy, the Moratorium on Groundwater Withdrawals, and policy debates related to stream buffers or riparian zones.

Jensen-Ryan’s fieldwork has carved out a network of inter-related, yet different parties. “I started fieldwork in September 2015 and so far I have completed 75 one-on-one semi-structured interviews with key actors (most in-person, some on the phone).”

It was exhaustive. She crisscrossed the breadth of Georgia and conducted focus groups. She traveled to various stakeholder meetings, including 11 with Georgia’s Regional Water Council, distributing questionnaires at each of their meetings. The work is confidential, but she has questioned those within the Environmental Protection Division, USGS, River Basin Center, UGA scientists all over campus, Georgia Tech scientists, Carl Vinson Institute, Atlanta Regional Commission, Metro North Georgia Water Planning District, all of the Regional Water Councils, Georgia Green industry, GEFA, Midtown Atlanta, Metro Chamber of Commerce, Georgia House of Representatives, Georgia senators, members of the Department of Natural Resources, and various environmental consulting firms whose names she strictly protects.

“Also, I’ve spoken with several members of each of these groups so that I am not getting skewed info from one individual. It has been a huge project with very high-profile individuals partaking.”

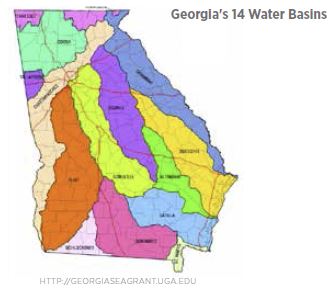

Georgia enjoys abundant natural resources overall. With more than 50 inches of annual precipitation, 14 major river systems and seven highly productive groundwater aquifers, Jensen-Ryan explains that Georgia has abundant water resources.

“Yet, water problems exist throughout the state where demands fueled by population and economic growth creates pressure,” Jensen-Ryan explains.

Now, she is creating a paper to consolidate her dissertation research for the use of boundary organizations, policymakers, governmental organizations, and other interested parties. Jensen-Ryan explains how academic scientists, those working at the boundary of science and policy, (the environmental protection division, for example), and decision makers play very different roles.

What does she predict concerning the future of water administration?

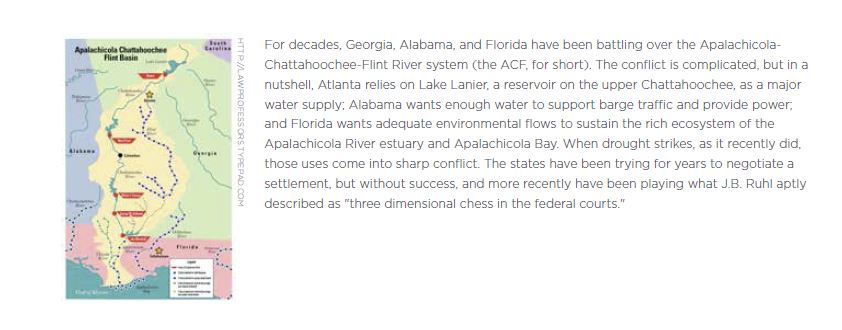

“I have been asking each of my informants this question,” Jensen-Ryan replies. “So far, most of them are just focused on the short-term and looking to how the Tri-state Water Wars will pan out. Also, most point toward a contested future which is similar to the one we have now in which development advocates and environmental groups are at odds.” But she concludes on a high note: “However, some of the facts are pointing to a wiser Georgia population regarding water and enhanced conservation and efficiency, both in Metro Atlanta and more rural Georgia.”

Scholarship in Aid of Social Action

Among a long list of awards, she was selected as a participant for the Graduate School Emerging Leaders Program in 2015. “Emerging Leaders has also been a significant highlight of my graduate experience,” she says.

“I have completed publications, presentations, assistantships, and research internships on various National Science Foundation projects during my graduate tenure at the University of Georgia. I have also prepared for a more applied career as I made significant inroads with those working at the forefront of environmental issues during my dissertation fieldwork.”

She was awarded a National Science Foundation Doctoral Dissertation Research Improvement Grant for her dissertation work concerning the environmental science policy interface.

This year, Jensen-Ryan also took on advocacy of a much more personal matter: Students diagnosed with BRCA. She threw her energies into creating a student organization she named BRCAn’t Stop Me.

“One final achievement of my graduate career has been starting a chapter of the national student organization BRCAn’t Stop Me at the University of Georgia, in an effort for students on our campus to have additional support when diagnosed with hereditary cancer genetic disorders in college,” Jensen-Ryan says.

“After undergoing several surgeries in Atlanta to handle my 2011 BRCA 1 diagnosis, I knew I had to create a network of individuals able to support each other facing similar life altering genetic health diagnoses at the University of Georgia. Thankfully, the University of Georgia and our local Athens community have embraced this organization through

partnerships with the University Health Center and the Loran Smith Cancer Center.”

Now, her eye is upon using her sense of activism to further science. “Given the growing divide between science and policy in the United States, exploring effective measures which can ultimately help create better science-based policy will be important as humanity faces increasingly intractable environmental problems,” she says.

Her interests in policy making have interested her in politics and government. It is also helpful that Jensen-Ryan has had a lifelong interest in the art of rhetoric and public debate.

“My ultimate lifelong goal is to run for political office. My experience giving presentations, facilitating focus groups and conducting interviews, debating within numerous debate organizations, structuring publicly engaged academic work with local communities and state governments, and actively participating in leadership courses and training positions me to become a political leader.”